|

In late June 1863 Robert E. Lee once again looked to capitalize on recent Confederate victories by moving his Army of Northern Virginia across the Potomac River and invading the northern states. Maryland once again was thrown into a frenzy as Lee’s army moved across the state. In Baltimore volunteers and soldiers were supplied shovels and pickaxes to build up the defenses of the city. Fort Federal Hill was supplied with rockets to alert Fort McHenry of approaching enemy forces and the majority of Confederate POWs held in Fort McHenry were placed on boats and shipped to other prisons.

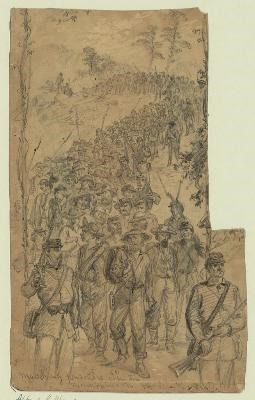

Library of Congress POWs ArriveOnce again Baltimore became a hospital town in the days following the Battle of Gettysburg as prisoners of war captured from the battle also began streaming into the city. Prisoners were primarily brought in by the railroad, and upon arriving in the city were marched to Fort McHenry for holding and eventual transfers to more permanent prisons or exchanges. By the end of July, the number of prisoners being held at the fort had swelled to 6,957. This included Confederate generals James Kemper and Isaac Trimble, both of whom had been seriously wounded as a result of the ill-fated Pickett’s charge on July 3rd.

By the end of August, most POWs had been transferred elsewhere with only about 54 prisoners remaining on site. Many ended up in the now swelling prison of Point Lookout, MD which was becoming more and more crowded and growing as one of the most notorious prison camps in the North.

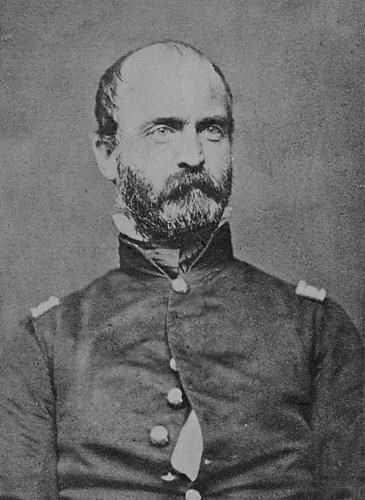

American Battlefield Trust A Somber HomecomingLewis Armistead was the nephew of Major George Armistead, who, in 1814, had famously led the defense of Fort McHenry during the Battle of Baltimore helping to inspire the Star-Spangled Banner. Lewis’s father had moved to North Carolina by the time he was born. His family’s illustrious military history helped him enter the United States Military Academy at West Point, though he never graduated having resigned after an incident in which he had broken a plate over the head of fellow cadet, and later Confederate general, Jubal Early. |

Last updated: August 13, 2020