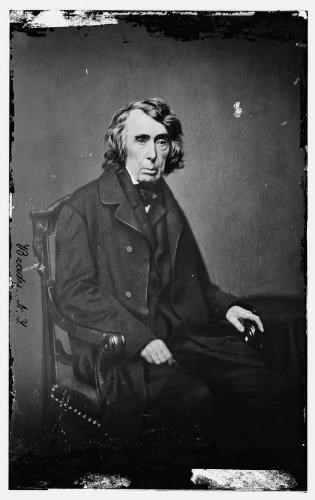

Library of Congress The Secession CrisisFollowing Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, Southern slave-owning states began to secede from the United States of America starting with South Carolina. In no place was there a greater rise in tensions than the state of Maryland. The northern most slave-owning state in the country, Maryland’s Mason-Dixon Line (it’s northern border with Pennsylvania) symbolized the division between slavery and freedom in the country. As the secession crisis grew, the question of whether Maryland would secede or remain loyal to the country grew more divisive.

Library of Congress Fort McHenry and Drastic MeasuresSome of the soldiers involved with the Pratt Street riots were on their way to Fort McHenry to help reinforce the garrison there. The fort’s commander, Capt. John C. Robinson, began preparations for a possible attack, building up the defenses and turning its large columbiad guns towards the city of Baltimore, threatening that if an attack were to come that he would fire upon Monument Square in the heart of the city. Although the Maryland Senate unanimously voted on April 26, 1861 that the state had no constitutional authority to consider secession and the House of Delegates concurred, fear of a secessionist uprising in Baltimore, and the state, did not go away.

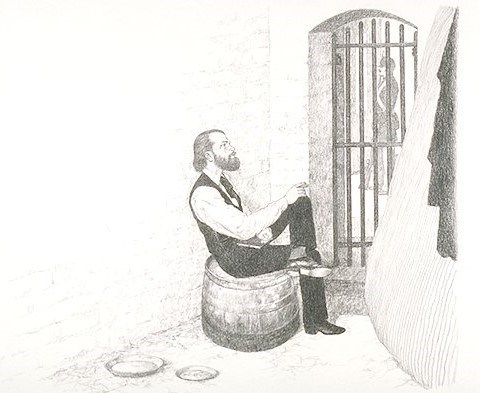

NPS/Harpers Ferry Center The American BastilleJohn Merryman was not the last person imprisoned under the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus. Many political figures and private citizens would find themselves in the confines of Fort McHenry throughout the war. In September of 1861 another attempt to vote for secession was planned in the state of Maryland, in response Secretary of War Simon Cameron gave orders that the legislative body of Maryland must not be allowed to pass such an act. On the night of September 11, 1861, a “political massacre” occurred in which 31 members of the Maryland legislature were arrested. In addition, the mayor of Baltimore, George W. Brown, and other prominent citizens were arrested. Most of the people arrested in the political massacre found themselves being held in Fort McHenry. |

Last updated: July 30, 2020