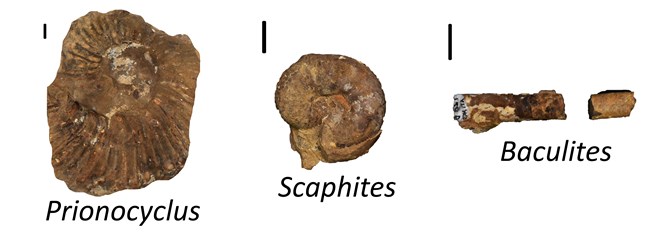

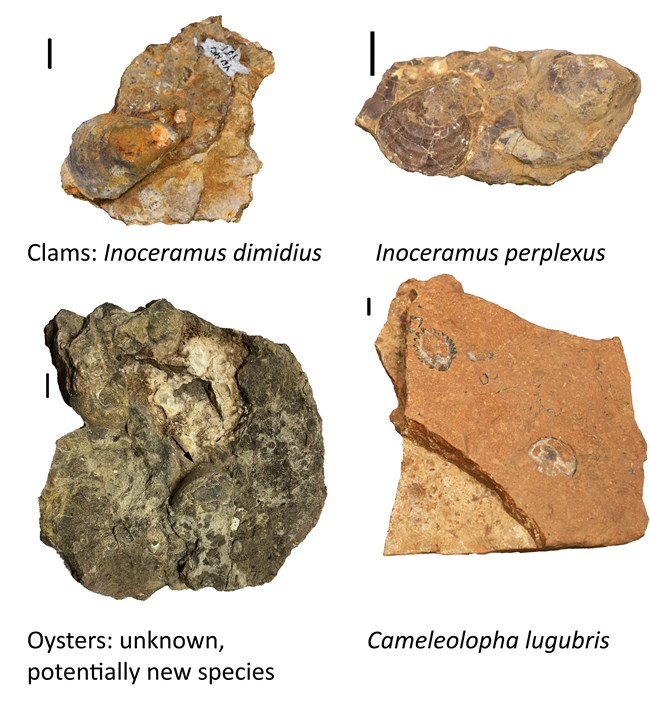

NPS/Karen Carr Studio Yet, the geologic features and processes in the region began influencing life long before human habitation. Millions of years ago—well before humans occupied the area—communities of ancient organisms thrived. This multimillion-year history of geology and life is recorded in the rock units and fossils that are present in the monument; thus, although the monument is known for is archeological resources, it has rich paleontological resources as well. The main bedrock unit at YUHO is the fossiliferous Mancos Shale, which was deposited during a time when the region looked much different than it does today. Today, YUHO sits more than a mile above sea level in the Colorado Plateau, but 90 million years ago (during the Cretaceous Period) the Rocky Mountains did not yet exist and the area was submerged by the Western Interior Seaway. The seaway hosted a variety of marine organisms. These organisms are preserved as fossils in the rocks at YUHO. There are fossils of clams, oysters, ammonites, and marine vertebrates. There are two species of clams, two species of oysters, six species of ammonites in three genera (plural of genus), and one vertebrate species (just a small unidentifiable bone fragment) that have been found in the rocks at YUHO. The three genera of ammonites are all easy to identify by non-paleontologists. Specimens of the genus Scaphites have loosely coiled shells shaped like the number nine. Specimens of the genus Baculites have straight or slightly bent shells; and specimens of the genus Prionocyclus have the tightly coiled or spiraled shells that even non-paleontologists often recognize as belonging to an ammonite. The majority of the fossils found at YUHO are in fossiliferous slabs of rock that were used as building stones by the Ancestral Puebloans. They likely collected the slabs from nearby outcroppings of the fossiliferous rocks, which are a half mile west of the structures they built. Presumably, the Ancestral Puebloans deemed these rocks important enough to collect and transport to use as building materials. This is an example of fossils in a cultural resource context; and it illustrates the interconnectedness of geologic history and human history. Fossils are non-renewable resources that have scientific and educational information and provide insight into what Earth was like in the past. Park staff and paleontologists work together to maintain fossils for scientific study and public education. It is exciting to find a fossil, but important to protect it. Report by Victoria Crystal Geologic Resources Division National Park Service

Base map by Scott D. Sampson, Mark A. Loewen, Andrew A. Farke, Eric M. Roberts, Catherine A. Forster, Joshua A. Smith, Alan L. Titus, 2010, and licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Graphic annotated by Victoria Crystal (NPS).

NPS/Victoria Crystal

NPS/Victoria Crystal and Samuel Denman |

Last updated: April 21, 2025