In response Weir wrote his brother, “I have exhibited these things because I recognize in them a truth which I have never felt before…my eyes, I feel, have been opened to a big truth.” His big truth was to create paintings that showed what he called the “character and aspect” of the subject; not necessarily a realistic representation of what he saw. Weir’s paintings of Branchville in the permanent collection of Weir Farm National Historical Park show the Connecticut countryside through his big truth: the sun-drenched fields of his farm contain both beautiful vistas and unsightly dying trees. Common subjects are beautiful and worth examining. Weir’s paintings are filled with impediments that intentionally slow down how fast a viewer can observe the painting. Boulders, trees, fences, and stone walls are the visual representations of his belief that one must spend time in nature before nature reveals its beauty.

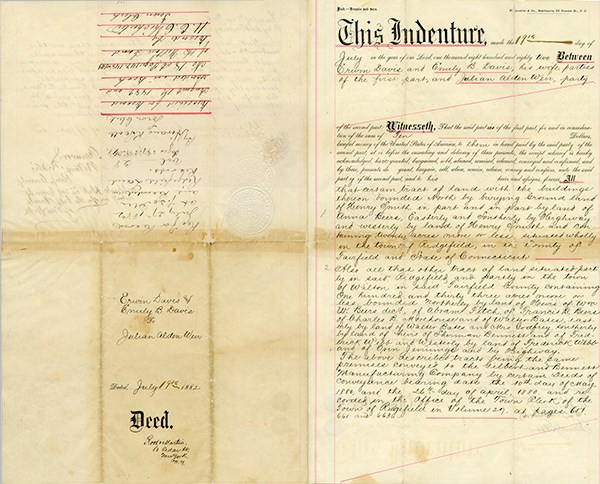

NPS Photo 1882 In June of 1882, art collector Erwin Davis offered Weir a 155-acre farm in the Branchville neighborhood of Ridgefield, Connecticut in exchange for a “flower” painting from Weir's private collection. Intrigued by the offer, Weir made the trip from New York City to see the farm. He quickly agreed to the sale. On July 19, 1882, the Davises signed the deed which formally transferred the property to Weir. The title of the flower painting and its artist are unknown. It is possible that future research will reveal the identity of both. Click on the deed to read its transcript.

NPS Photo 1882 Watercolor on Paper Painted during Weir’s first visit to Branchville, this small watercolor is the template of how he would create future paintings of his farm. Although the painting is framed in a traditional sense, the composition of the painting is unexpected. The small field leads up the left side of the paper, the opposite way of the western tendency to read. A stone in the lower center of the painting acts as a barrier that breaks up the expanse of the scene and forces the viewer to look around it. Weir often used similar obstruction techniques and an unexpected composition when he painted the Branchville landscape.

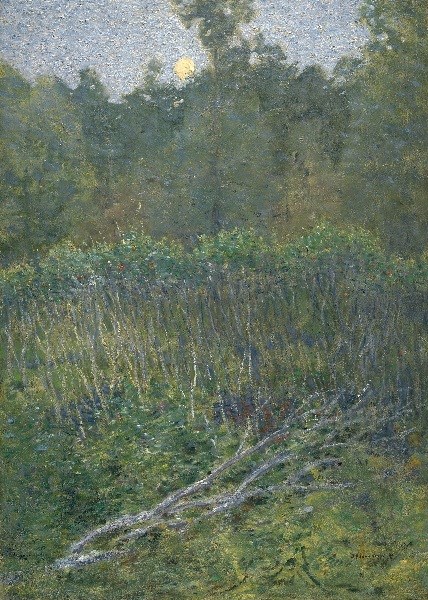

NPS Photo Oil on Canvas 1891 Weir recognized that his best paintings are among the hardest to understand. A viewer needs to take time to look at it, to see the same “character and aspect” that Weir saw as he was painting. Early Moonrise is one of those paintings. It is composed in three horizonal bands: brush and fallen branches across the bottom, a group of trees in the center, and a small sliver of blue sky with a yellow moon at the top. At first glance, Early Moonrise is a flat, dense wall of color. But after taking time to study it, Weir’s techniques of broken brushstrokes in the foreground, dry looking brush work in the center, and thicker daubs of paint in the background are revealed. Small pops of color become visible, and we can begin to detect Weir’s unique view of nature.

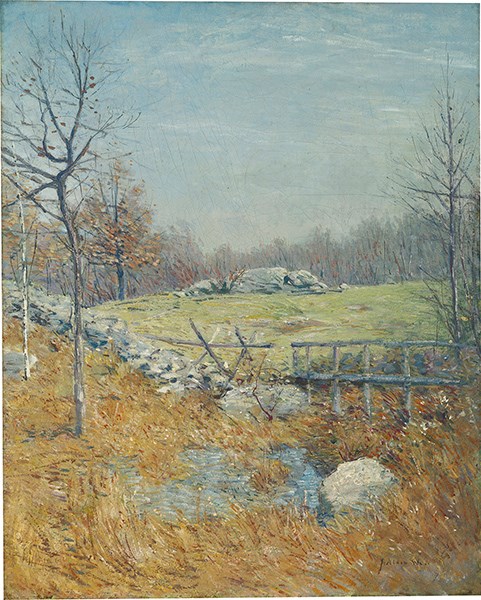

Oil on Canvas 1906 Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, William A. Clark Collection. Do you notice how the wetlands and stone walls lead up the left side of the canvas again? Or how the water in the lower center of the canvas is reminiscent of a bolder? Twenty-four years after Spring Landscape, Branchville, Weir still used some of the same basic composition and obstruction techniques that he applied in Autumn. One art historian suggested that Weir knew he made Autumn too difficult to appreciate and his 1915 painting, The Fishing Party was made in response. Weir painted the same scene again, but this time he added a small group of figures on the bridge. These figures appear to be seen from a distance, suggesting the viewer should be far away from the bridge. This change makes the wetlands in the foreground less of a visual impediment in The Fishing Party than in Autumn.

NPS Photo Pastel on Board Undated Dorothy Weir Young wrote that her father disliked “having everything taken in at a glance but preferred instead that things should disclose themselves to you gradually, when you were least expecting it.” Most of this pastel depicts the sun-dabbled ground and trees above the pond. Weir then placed a tree in the center of the pastel, limiting the small view of the pond. Weir often used trees to block views or paths in his paintings as a visual metaphor of his belief that one must take time in nature to truly see its beauty.

NPS photo Oil on Canvas ca. 1910 Weir once wrote, “I don’t like what others find attractive.” When he said this, he was speaking about a winding country road, but the same could apply to this painting. A barway is an opening in a stone wall for wagons to drive through. This is the not the beautiful landscape that one would expect at first glance. Note the dead tree dominating the foreground and the vista of the landscape broken up by the intersection of several stone walls. Even the two stately trees in the background are cut off. As the viewer’s eye moves past the dead tree and stone walls, it takes in the sun lighting up the small, pink tree hidden behind the bare branches. The ends of the stone wall and courtyard are bathed in sunlight, welcoming viewers to step out of the shadows.

NPS Photo Oil on Canvas ca. 1907-1910 Foggy Morning, one of Weir’s few nocturnes, or night paintings, is a departure from his usual sunny depictions of Branchville. The moon glows pink, creating a mystical feeling. Perhaps Weir was inspired by his friend Childe Hassam, who was painting nocturnes such as 5th Avenue Nocturne at this time. Although the mood is different, Weir still relies on his common obstruction techniques in this painting. The cows are hidden behind the cedar split rail fence. Even the moon, so important to this painting, is nestled between the branches of the large tree. Research suggests that Weir never finished this painting to his liking. That is not surprising since he once wrote, “I would like to paint this night sometime. But it isn’t paintable. No, it cannot be done by man. What a mystery it all is.”

Acknowledgements Weir Farm National Historical Park thanks Dr. Doreen Bolger and the late Hildegard Cummings for their scholarship and study of Julian Alden Weir. This exhibit would not have been possible without their observations and insights. |

Last updated: May 4, 2022