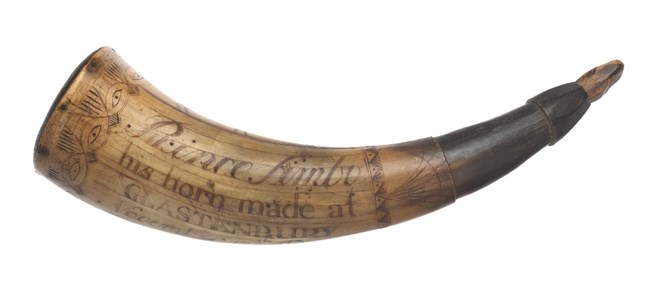

Image Credit: Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture Prince Simbo (1740 or 1750-December 14, 1810) – In 1777, Prince Simbo joined Captain Ebenezer Hills's Company in the 7th Connecticut Regiment, Huntington’s Brigade, First Division.1 He enlisted in Glastonbury, Connecticut—as did Sampson Freeman and six other Black men throughout the war.2 Simbo most likely enlisted as a free man, though the evidence remains inconclusive.3 If free, he “likely had more significant rights and privileges associated with membership to the militia” prior to enlistment.4 Prince Simbo

1. “Private Prince Simbo, Valley Forge Legacy: The Muster Roll Project, accessed December 11, 2020, http://valleyforgemusterroll.org/muster.asp.

2. Maurice A. Barboza, “The Hometowns of Connecticut’s African American Revolutionary War Soldiers, Sailors and Patriots,” National Mall Liberty Fund D.C., accessed December 11, 2020, https://libertyfunddc.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/HARTFORD-COUNTY-BACKGROUND-AFRICAN-AMERICAN-REVOLUTIONARY-WAR-RESOLUTION.pdf. 3. Alex Palmer, “The Revolutionary War Patriot Who Carried This Gunpowder Horn Was Fighting for Freedom—Just Not His Own,” Smithsonian Magazine, June 22, 2016, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/patriot-who-carried-revolutionary-war-era-gunpowder-horn-was-fighting-freedomjust-not-his-own-180959385/. 4. Alex Palmer, “The Revolutionary War Patriot Who Carried This Gunpowder Horn Was Fighting for Freedom—Just Not His Own.” 5. Ibid. 6. “United States Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9WB-M61V?i=769&wc=M61K-F36%3A355079501&cc=2068326 : 21 December 2016), 20-Connecticut (jacket 121-124) > images 770, 776, 779, 785, 880, 885, 887, and 889 of 892; citing NARA microfilm publication M246 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1980). 7. R. Gregory Lande, MC USA (Ret.), Invalid Corps, Military Medicine, Volume 173, Issue 6, June 2008, Pages 525–528, https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED.173.6.525, quoted in B. Stinson, The Invalid Corps. Civ War Times Illus 1971; 10: 20–7. 8. “United States Census, 1790,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9YYY-5ZW?cc=1803959&wc=3XTM-1TS%3A1584071302%2C1584071354%2C1584071161 : 14 May 2015), Connecticut > Hartford > Glastonbury > image 3 of 6; citing NARA microfilm publication M637, (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.). 9. Ancestry.com. Connecticut, U.S., Church Record Abstracts, 1630-1920 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: 2013. Original data: Connecticut. Church Records Index. Connecticut State Library, Hartford, Connecticut. 10. Alex Palmer, “The Revolutionary War Patriot Who Carried This Gunpowder Horn Was Fighting for Freedom—Just Not His Own.” 11. Alex Palmer, “The Revolutionary War Patriot Who Carried This Gunpowder Horn Was Fighting for Freedom—Just Not His Own.” |

Last updated: February 2, 2021