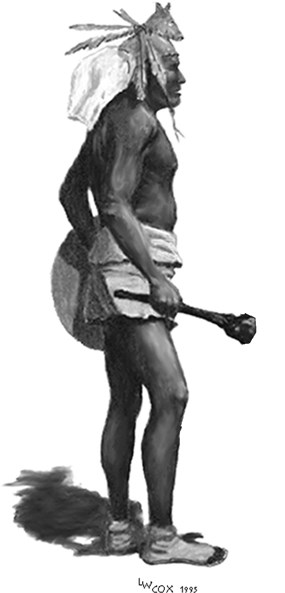

His charisma was big, his bravery was undisputed, and he had tactical skill enough to impress everyone. That made him a perceived threat to the missionaries he dealt with. Luis Oacpicagigua was a complex figure of the Pimería Alta. In another culture he would have had broad support and could have led a successful rebellion against the Spanish. Unfortunately for Luis, he was part of a culture where leadership stopped with the family group, and where outsiders, even O’odham outsiders, were mistrusted. Luis became part of an O’odham force that aided the Spanish in one of their many wars against the Seri. The Seri were an indigenous people in the Gulf of California, who were not susceptible to Spanish material culture and resisted the cultural influences of Spain. The O’odham fought valiantly and successfully routed the Seri. They were, in fact, more successful than their Spanish allies. Luis returned with a renewed appreciation of his own tactical and leadership skills. Reinforcing his estimation of himself, Spanish political authorities rewarded him, giving him an officer’s uniform and the title of Captain-General, a rank signifying a general of armies with the authority of a Governor. They also bestowed on him a silver-headed baton, a significant representation of power. The Spanish might have seen the awards as symbolic, but for Luis they had anointed him head of all the O’odham people. His ego also fed a dangerous conclusion. He had been unimpressed by Spanish martial skills and he began to question the might of Spanish arms. He must have realized how thin the Spanish military was spread (only 75 Spanish soldiers were in the offensive, compared to 400 native auxiliaries), and how isolated the overbearing missionaries were. It could not have been lost on him that Spanish settlers were encroaching on O’odham land in increasing numbers, disregarding O’odham property and abusing O’odham laborers. His exalted return was deflated upon returning to the mission. He was derided for his ostentatious display of military rank. He had been caught in lies against some of the mission neophytes. His lieutenants were humiliated. His authority, it seemed, was illusory. He had returned from the glorious battlefield to be nothing. In the past Luis’ loyalty to Spain had been unquestioned. In 1749 he had been an ambitious recruiter of Desert O’odham into the missions, demonstrating a belief in Spain’s path to the future. Now, he saw the Spanish as weak and divided. He must have known that the Jesuit priests were at odds with the civil government and he saw opportunity. He began to believe that the Spaniards were vulnerable, and a concentrated, coordinated rebellion could drive them from the frontier. Such a war would require a talented leader with seasoned soldiery. He had both at his disposal. The plotting took months and the coordination was successfully done in secret. Each targeted mission or village had a band of rebels who would move in unison. The revolt, occurring at night was to have the Spanish dead or in flight by first light. The revolt exploded in the night on November 20, 1751. Luis was ruthless and the night was bloody and fiery. He was indiscriminate, seemingly swallowed by rage. He murdered family members, other O'odham, servants and enslaved people. The rebels killed two priests, one of whom had just reached the frontier. The revolt continued through the next day. The Spaniards retreated quickly, in great fear. The rebels, with no one to attack, stopped. The O’odham do not have a warrior society and there is no traditional passion for war. The excitement for vengeance dissipated. The rebellion dissolved. According to Roberto Salmón, Luis had failed to rally mission O’odham and his leadership “extended only over those leaders who lacked mission ties.”* Only those who rejected Spanish authority were enthusiastic about revolt. The Sobáipuri along the San Pedro River, in the valley to the east, refused to cooperate. Northwestern O’odham rejected Luis’ authority. A delegate to the Chiricahua Apache was sent home. Luis retreated to the Santa Catalina Mountains north of Tucson and began sending entreaties of peace. In the background of the negotiations, the Spanish were slinging blame for the uprising. In the midst of the threat felt by the frontier settlers, the Spanish displayed the same divisiveness that made Luis believe they were vulnerable in the first place. For the rebels, the in-fighting between church and state, saved them from execution. Luis arrived in Tubac on March 18, 1752 and swore an allegiance to the King. He asked for mercy. The Captain that accepted his surrender considered him to represent a warring nation and with a truce in place allowed Luis to return to the Catalinas to retrieve his followers. Good to his word, Luis returned on March 22 with his wife and three children. The Captain retired south with his cavalry. Luis was without influence. He became, as one researcher framed him, “a marginal man.” Luis lost face with his own people for his easy surrender to the Spanish. He lost trust with the Spanish, and the governor who had been his key protector was promoted away from Sonora. The Jesuits were cleared of charges and left in place, masters of both the missions and the northern frontier. Resistance continued, though not in any flourish of battle. Though a new fort was established in the Santa Cruz Valley in June 1752, the troops spent their time hunting down pockets of rebels who had created a hideout in the center of sacred O’odham country. Luis apparently talked of stoking the ashes of rebellion again. Interest among the rebels for his leadership was lacking, and sympathetic O’odham kept the Spaniards aware of his plots. In May 1753 the Spanish arrested Luis on suspicion of plotting a rebellion. There was no sympathetic governor this time and he was interrogated. After an attempted suicide, he was placed in prison in Horcasitas, where he died. Learn more in Luis of Sáric's entry in the original mission records and follow the blue ID numbers. |

Last updated: May 6, 2025