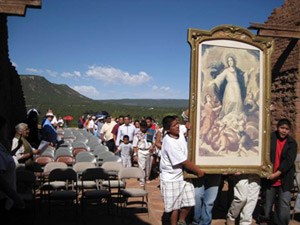

Mission Nuestra Señora de Porciúncula

Pecos Pueblo, Pecos National Historical Park, New Mexico

Coordinates: 31.567472,-111.051842

#TravelSpanishMissions

Discover Our Shared Heritage

Spanish Colonial Missions of the Southwest Travel Itinerary

Photo by Patricia Lenihan.

NPS photo by Heather Young.

Photo by Roger Clark.

NPS photo from Pecos NHP Visitor Center Museum.

Plan Your Visit

Pecos National Historical Park, a unit of the National Park System and a National Historic Landmark, (NHL text and photos) is located off Interstate 25, 25 miles east of Santa Fe, NM. Click for the National Register of Historic Places file: text and photos. Pecos National Historical Park Visitor Center and Trail are open daily from 8:00am to 6:00pm during the summer. The trail’s winter hours are from 8:00am to 5:00pm, and the visitor center closes at 4:30pm. The park is closed on Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Day and New Year's Day. There is an admission fee. For more information, visit the National Park Service Pecos National Historical Park website or call 505-757-7200.

Pecos National Historical Park has been documented by the National Park Service’s Historic American Buildings Survey. Pecos National Historic Park is also featured in the National Park Service American Southwest Travel Itinerary, the Places Reflecting America’s Diverse Cultures: Explore their Stories in the National Park System Travel Itinerary, and the American Latino Heritage Travel Itinerary.

Last updated: April 15, 2016