This article discusses the resiliency components and provides examples from cultural landscapes in national parks across the country. It is intended to stimulate thought about sustainable practices and the ways in which cultural landscapes can be managed through preservation maintenance or rehabilitation treatment for greater resilience to the effects of changing climates.

The article was originally written by program staff for publication in:

Chris Beagan and Susan Dolan. "Integrating Components of Resilient Systems into Cultural Landscape Management Practices." Change Over Time 5, no. 2 (Fall 2015): 180-199.

Resilience

Cultural landscape managers are seeking to enhance the ability of landscapes to endure stressors, disturbances, and environmental change. The components of resilient systems—diversity, redundancy, network connectivity, modularity, and adaptability—are valuable tools to examine current landscape vulnerability and to attempt to minimize climate change impacts. These components are derived from the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s ‘‘National Incident Management System’’ and were recently included in the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Rebuild by Design competition brief.1

This article discusses the resiliency components and provides examples from cultural landscapes in national parks across the country. It is intended to stimulate thought about sustainable practices and the ways in which cultural landscapes can be managed through preservation maintenance or rehabilitation treatment for greater resilience to the effects of changing climates.

Cultural landscapes are historically significant properties that show evidence of human interaction with the physical environment. In the United States National Park Service (NPS), their significance is evaluated based on their physical integrity and associations with people, events, or trends that have shaped American history. Cultural landscapes across the nation are managed so as to preserve those aspects of their physical character that convey their historical significance.

The federal government’s management principles are outlined in The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties with Guidelines for the Treatment of Cultural Landscapes Standards, which include four treatment approaches: preservation, rehabilitation, restoration, and reconstruction.

Cultural landscapes are inherently dynamic.

Preservation is the treatment with the objective of retaining the extant historic character of a landscape. This treatment is applied and sustained through the ongoing preservation maintenance practices of care, repair, and replacement in-kind. Specialized techniques are used in preservation maintenance to conserve historic character, but the techniques can be adapted to better support living systems and favor environmental health. For example, lawn care techniques can be modified to more sustainable methods without altering the historic character of a lawn. As preservation maintenance is the default approach to cultural landscape management before and after any treatment is applied, some flexibility to increase resilience may be found in the ongoing preservation of any landscape.

Rehabilitation is the treatment with the objective of designing changes to a cultural landscape that are compatible with and conserve the historic character of the landscape. In The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards, rehabilitation allows for ‘‘a compatible use of a property through repair, alterations, and additions while preserving those portions or features which convey its historical, cultural, or architectural values.’’2 Rehabilitation emphasizes protection and preservation of extant historic features, repair of deteriorated historic features, and replacement in-kind of severely deteriorated or missing historic features.

At the same time, rehabilitation also acknowledges the need to meet changing conditions through alterations or new additions, while perpetuating the historic character of the property. Compatible alterations or additions through rehabilitation are the philosophical basis for making design changes that improve the sustainability of cultural landscapes, while maintaining the characteristics and features that contribute to historical significance. After implementation, the treatment is perpetuated through preservation maintenance.

Cultural landscapes are inherently dynamic. Changing conditions, as a result of both cultural and natural forces, necessitate adaptive management. Cultural forces that may necessitate adaptation are largely understood. They can include changing cultural or land use practices; changing demographics or the needs of users; and the changing availability of stewards’ time, funding, and materials, among other factors.

NPS

However, in recent decades, the physical environment is experiencing changes at an unprecedented rate. In light of present environmental and cultural conditions, landscape managers are seeking sustainable adaptations to change that perpetuate and enhance the historic character of the resources that they steward.

Mitigating risk is a cornerstone of nearly all climate change response plans across the globe, including the Climate Change Response Strategy published by the National Park Service.3 Reducing greenhouse gas emissions and enhancing the capacity of landscapes to sequester and store carbon is central to reducing the potential for future climate change impacts. Simultaneously, adaptation increases preparedness for future impacts that cannot be avoided. Building the capacity of cultural landscapes to respond to unanticipated change is an integral step in mitigating and adapting to climate change.

Resilience is defined by a capacity to withstand change or recover from unexpected impacts quickly. According to the National Disaster Recovery Framework prepared by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, resilience is the ‘‘ability to adapt to changing conditions and withstand and rapidly recover from disruption due to emergencies.’’4 As interpreted by the Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force in its Rebuild by Design competition brief, resilient systems have five components: diversity, redundancy, network connectivity, modularity, and adaptability.

NPS, 2008

Of course, there is no one means for building resilience, no single approach to mitigating impacts, and no panacea for combating climate change. These five components, as expounded in this publication, offer a simple conceptual framework to be integrated into the decision-making process for cultural landscape preservation maintenance and rehabilitation treatment.

Both treatment and maintenance projects offer opportunities to enhance the resilience of cultural landscapes—for example, their diversity, redundancy, network connectivity, modularity, and adaptability characteristics—through physical intervention. The examples that follow are drawn from NPS rehabilitation treatment and preservation maintenance projects in cultural landscapes and relate mostly to vegetation management.

Five Components of Resilient Systems

Although only one of the five components of resilient systems is highlighted in each of the examples, many of the examples demonstrate more than one component. Ultimately, the most resilient cultural landscapes are defined by multiple components of resilient systems functioning in association with each other.

-

Diversity

DiversityDiversity is a safeguard against catastrophic loss by allowing a wide range of responses to stress.

-

Redundancy

RedundancyRedundancy provides backups in the event of stress, loss, or failure.

-

Network Connectivity

Network ConnectivityNetwork connectivity refers to the types and degrees of system interactions that promote robustness and discourage brittleness.

-

Modularity

ModularityModularity allows structurally or functionally distinct parts to retain autonomy during a period of stress with easier recovery from loss.

-

Adaptability

AdaptabilityAdaptability is to the ability of a system or feature to function under stress and our ability to adjust management practices for change.

-

Resiliency in Action

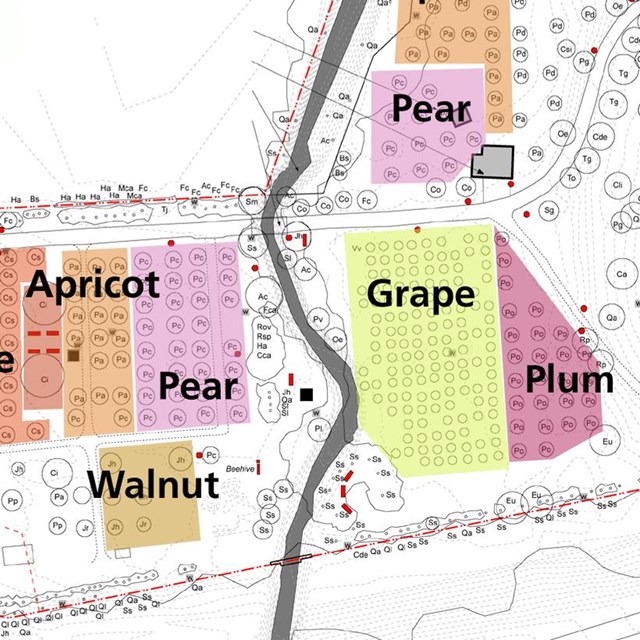

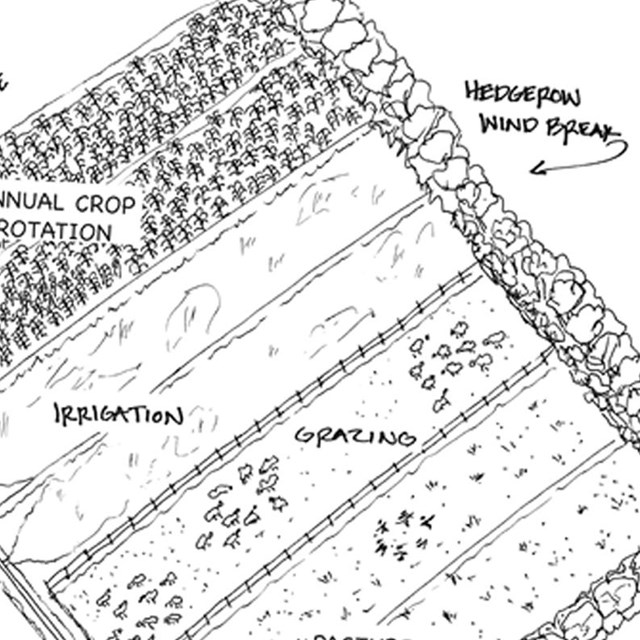

Resiliency in ActionA resilience approach to sustainable cultural landscape management at Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site.

1. Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force, Rebuild by Design: Hurricane Sandy Regional Planning and Design Completion, Design Brief (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2013), https://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=REBUILDBYDESIGNBrief.pdf (accessed October 15, 2014).

2. Charles A. Birnbaum and Christine Capella Peters, eds., The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties with Guidelines for the Treatment of Cultural Landscapes (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, 1996), 48.

3. Climate Change Response Strategy (September 2010), National Park Service Climate Change Response Program,https://www.nps.gov/subjects/climatechange/upload/NPS_CCRS-508compliant.pdf (accessed November 12, 2014, URL updated October 4, 2021).

4. National Disaster Recovery Framework: Strengthening Disaster Recovery for the Nation, Federal Emergency Management Agency, www.fema.gov/pdf/recoveryframework/ndrf.pdf, 81 (accessed November 12, 2014).

Last updated: October 22, 2024