|

Mountain yellow-legged frogs (Rana muscosa and Rana sierrae) are amphibians that inhabit naturally fishless lakes, ponds, and streams in the high country of the Sierra Nevada mountains. Once the most numerous amphibians in the Sierra Nevada, today mountain yellow-legged frogs have disappeared from 92% of their historic range. As a result, in 2012 Rana muscosa was listed as endangered and Rana sierrae was listed as threatened under the California Endangered Species Act; and in 2014 both species were listed as endangered under the federal Endangered Species Act.

National Park Service How did this happen? Extensive research identifies two main reasons for their decline. First, trout were introduced in high-elevation lakes to draw recreationists and tourists to the area. This created an imbalance in the natural world. Trout eat tadpoles and small frogs and compete with frogs for insects. In addition, trout restrict frogs and tadpoles to small, low-quality areas and separate frog populations from one another. As a result, many mountain yellow-legged frog populations have died out. In addition, a fungal disease called chytridiomycosis is threatening the existence of frog populations that had once thrived in fishless areas. The disease affects the skin of frogs and causes most infected animals to die. As the famous conservationist John Muir once said, "When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe." Frogs are a very important link in the food chain, or the order in which animals feed upon other plants and animals. For example, the sun provides food for grass. The grass is eaten by a grasshopper. The grasshopper is eaten by a frog. The frog is eaten by a snake, and the snake is eaten by a hawk. Removing the frog from the food chain, if eaten by trout, limits food for other animals and disrupts the natural cycle.

National Park Service Studies in the parks show that introduced trout harm entire ecosystems, not just mountain yellow-legged frogs. Trout are effective hunters who eat other amphibians, aquatic insects and zooplankton (small animals that naturally drift in water) leaving less food available for other wildlife. With a helping hand, the mountain yellow-legged frogs staged an impressive recovery. In 2001, park staff began using large nets and electrofishers (a device that temporarily stuns fish) to physically remove trout from selected waters. The goal was to restore the balance of nature to the pre-trout environment, with a focus on improving the health of mountain yellow-legged frogs. By 2011, nearly 44,000 fish were removed from 19 lakes, including complete removal from 9 lakes.

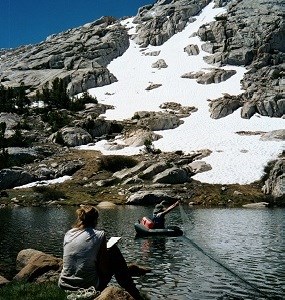

National Park Service In one restoration area, in remote lakes and streams of Upper LeConte Canyon, frog surveys conducted by park staff each summer season recorded the stunning progress. From 2001, when fish removal began, to 2004, after most of the fish had been removed, the number of mountain yellow-legged frogs/tadpoles in three restoration lakes increased from nearly 190 to over 18,800 - a 10,000% increase! From 2005 to 2011, during the removal of the remaining few fish, the population of frogs/tadpoles in these lakes stabilized, with numbers ranging from a 1,900-6,000% increase. In addition, over 2,000 frogs moved into two nearby lakes. As a result, the frog population increased to the point where it is now in a much stronger position to deal with other threats, such as disease. Due to these efforts, the natural balance has been restored for this population of mountain yellow-legged frogs. Hardy hikers in Upper LeConte Canyon may see many frogs or hear frequent "plops" or splashes near lakes and streams in summer. Other visitors may observe frogs laying eggs, see thousands of tadpoles as the waters warm, or learn about the project through park staff near the restoration areas. In addition, although introduced trout are being removed from selected waters to improve conditions for the parks' wildlife, trout will remain in hundreds of lakes and ponds in the parks, and ample opportunities will continue to be available for recreational fishing.

|

Last updated: January 15, 2026