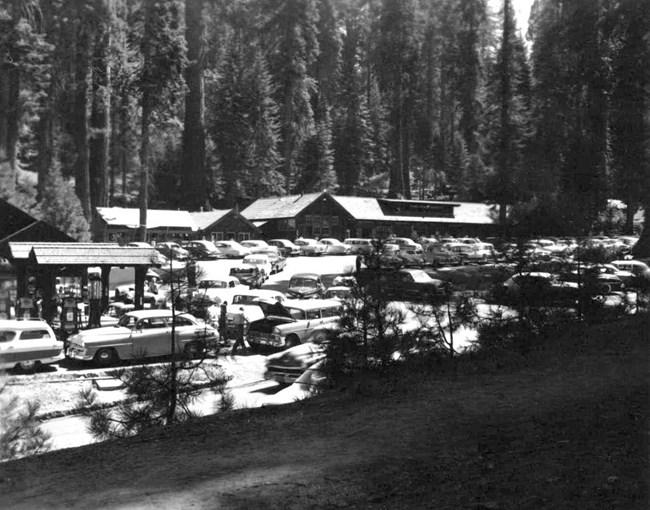

The Early YearsCommercial recreational use of Giant Forest began in 1899 with the construction of a tent camp that was accessed via pack train. In 1903 a proper road was completed and the tent camp grew accordingly. The terminus of the road at Round Meadow became the location for a ramshackle assemblage of semi-permanent summer camps, along with administrative and concessioner buildings. Ensuing campaigns to draw people to the national parks in general, and to see the "big trees" in particular, produced an eightfold increase in visitation. For example, the first formal lodge was erected in the summer of 1915 in anticipation of visitation spilling over from the Panama-Pacific Exhibition in San Francisco. In 1921, the concessioner erected the cabins that formed the core of the lodging area next to Round Meadow, for which the name "Giant Forest Lodge" was first applied in 1926. In the same summer, "Camp Kaweah" (Upper Kaweah) was established with the goal of pulling overnight development away from Round Meadow. Pinewood was developed in 1931 with the same goal. All this led to an infrastructure that by 1930 amounted to four campgrounds, dozens of parking lots, a garbage incinerator, water and sewage systems, a gas station, corrals, and over 200 cabin, tent-top, dining, office, retail, and bath-house structures. Many of these were located directly among stands of monarch sequoias.

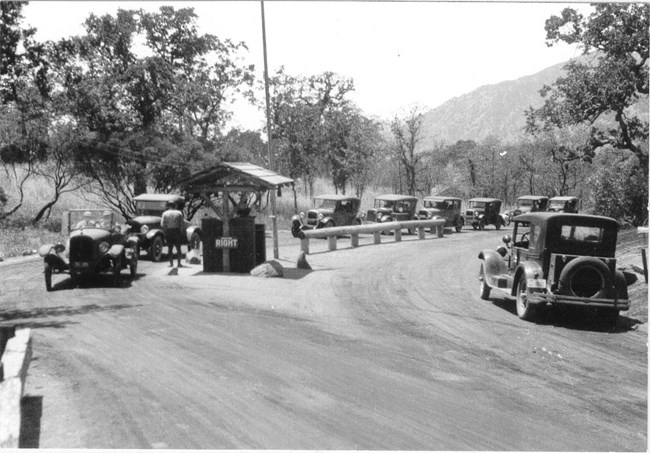

NPS Photo By the late 1920’s, the first voices decried this already disturbing human impact on the Giant Forest. These voices came from two different sources, each of which were to play major roles in the restoration of the grove. The first of these sources was Emilio Meinecke, an eminent forest pathologist. He was commissioned by NPS Director Stephen Mather to study the "effects of tourist traffic on plant life, particularly big trees" in Sequoia National Park. In 1926, Meinecke reported that humans were heavily impacting the Giant Forest. The second voice was that of Colonel John White, superintendent of Sequoia National Park. He was appalled by the congestion and over-development of the grove. In 1927, he suggested that the Giant Forest Lodge cabins be removed. The efforts of these two groups, science and NPS management, were to gain power fitfully during ensuing decades.

NPS Photo Another voice to arise in the late 1920’s was that of the park concessioner, the Sequoia and General Grant National Parks Company (subsequently, the Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks Company). This fledgling company immediately recognized the commercial value of the Giant Forest. Indeed, by 1941, the company owned 180 buildings in the grove.

NPS Photo The Impact of ScienceIn the 1920s, Emilio Meinecke put considerable effort into understanding the human impact on the big trees. Generally speaking, however, the application of scientific research to Giant Forest management increased sluggishly during the mid-1900s. During these years, landscape architects directed most land- use planning. The science of ecology was in its infancy. While modern landscape architecture is grounded in the science of ecology, the early application of landscape architecture was more geared toward swift, visually appealing results that were appropriate to parks managed for the enjoyment of people. As the 1900s progressed, natural sciences gained importance and played an increasingly significant role in park policy decisions. This was to have a profound effect on park management and the Giant Forest.

NPS Photo Planning and the PublicIn 1962 and 1965 Richard Hartesveldt submitted a pair of influential reports to the National Park Service. In these reports, Hartesveldt concluded that humans were adversely affecting the sequoias of the Mariposa Grove in Yosemite National Park and the Giant Forest Grove in Sequoia National Park, but in ways not previously suspected. Hartesveldt found that altered hydrology in the Mariposa Grove and increasingly dense competing vegetation in the absence of natural fire in both groves were causing the most severe impacts to sequoias. Impacts of development on sequoias were most damaging where major roots had been cut for road construction. Although Hartesveldt did not find other results of development - covering of roots by asphalt, soil compaction, or soil erosion - to cause profound impacts to sequoia survival or growth, he suggested that their probable effects on future sequoia health warranted action by the National Park Service. |

Last updated: October 16, 2024