|

With gravestones dating to 1704, the cemetery at St. Paul's Church National Historic Site is one of the oldest, continuously used burial yards in the nation. It evolved from a colonial burial ground serving the entire community to a church cemetery characterized by private family plots. The 5-acre yard contains a stunning variety of stones, religious and secular imagery, carving styles, epitaphs and even burial chambers. The appearance of the cemetery has been influenced by changes in religious beliefs and wealth, the development of stone carving as a profession and such broad cultural trends as the classical revival of the early 19th century. The yard reveals a remarkable story of continuity and change in attitudes toward death and salvation over a period of 300 years. Images of many of the gravestones are available here.

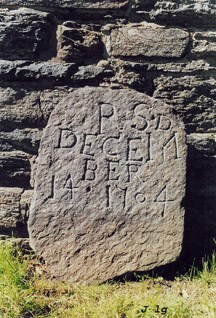

St. Paul's, for Richard Shute, who died on December 14, 1704. NPS The Earliest Stones The oldest legible gravestone at St. Paul's, for Richard Shute, who died on December 14, 1704.The origins of the St. Paul's cemetery were determined by the background and customs of the residents of the Town of Eastchester, which was founded by English settlers in the 1660's. Burials began around 1700 in the northwestern corner of the site, shortly after the completion of the town's first church, following the English tradition of the churchyard as burial ground. Before that, interment had usually occurred on family property. In a small, locally oriented town, grave markers were simple fieldstone, drawn from the fields of Westchester County. The population was small enough that initials were sufficient to identify the deceased and greater emphasis was given to recording the date of death, at a time when there were no death certificates. To chisel the simple inscriptions, the family hired the local blacksmith, who was skilled in the use of hand tools, but certainly not a professional carver, which was an additional reason for the minimal characters on a stone. Markers were austere and lacked imagery, because Eastchester's residents, raised in the Puritan tradition, feared that spiritual depictions would lead to idolatry, the worship of physical objects as gods.

NPS The First Symbols The earliest symbolism on gravestones at St. Paul's dates to the 1750's and takes two general forms. One is the heart, generally understood to have symbolized God's love, and the other is a star-like design or pinwheel, which probably represented heaven, or all things under heaven. These emblems were the first steps away from Puritan beliefs that prohibited any form of religious iconography. Both of these designs also appeared on 18th century furniture, clothing and everyday objects such as footwarmers, where they had an artistic as well as a symbolic function. The stones on which these designs appeared usually consisted of low-grade marble, worked into tripartite shapes. The designs appeared either in tympanum -- the arched middle section -- or on the side finials.

NPS An American Art Form The soul effigy on this sandstone marker for Elezebeth Clements, who died in 1762, was chiseled by John Zuricher, a leading colonial gravestone carver in New York. In the second half of the 18th century, the town's Protestant residents introduced tombstone symbolism that revealed attitudes toward death and salvation. The haunting skull and crossbones, reminding observers of their mortality, served as admonishments to improve moral behavior before it was too late. The beautiful cherub or soul effigy reflected a more positive view of the chances for salvation, with the winged angel, crowned with righteousness, representing the soul of the deceased rising to heaven. Epitaphs or short poems enhanced these themes. An array of social and economic changes contributed to this alteration in the appearance of the St. Paul's churchyard. Greater wealth among some of the families and increased commercial contact in the Hudson Valley led to the introduction of sandstone grave markers, drawn from quarries in New Jersey or Connecticut. Orders for the stones were forwarded to skilled carvers living in New York City or New Haven, using the Post Road connection, and finished grave markers were transported to Eastchester by boat. Many of those stones included the tripartite top -- similar to the headboard of a bed -- which represented the final resting place of the deceased.

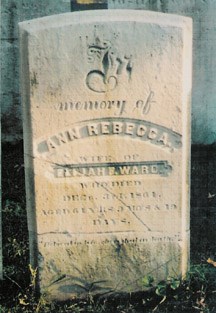

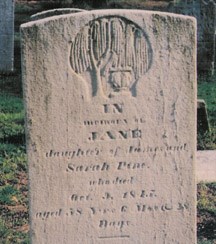

NPS In Memory of … This gravestone shows the calligraphic 'In' and letters in relief, popular features on "In Memory of" stones. By the end of the 18th century, as the use of the cherub-like soul effigy declined, a new form of gravestone emerged that emphasized calligraphy over iconography. These stones, which were both sandstone and marble, evoked the memory of the deceased rather than simply marking a grave site. Inscriptions began with the words, "In Memory of," or "Sacred to the Memory of." Though lacking pictorial elements, the In Memory of stones had a decorative element achieved through the carving of a Gothic "In" or of letters in relief, the combination of capitals and small letters, and the use of script, italics or different type faces. The stones generally displayed epitaphs, as wordy as survivors could afford, and it is in these verses that religious sentiments continued to be expressed. All of the "In Memory of" stones are thin-slab markers for single graves, or occasionally for the husband and wife. In other ways they reflect the economic circumstances of the deceased. The calligraphic phase of tombstone design was gradually eclipsed by the classical revival, which began in the early 1800's.

NPS Reviving the Ancient Republics The urn and willow are both featured on this 19th century marble gravestone. In the early 1880's, a classical revival which evoked the great ancient republics of Greece, and especially Rome, swept across the United States, the leading republic of the day. Furniture, architecture, decorative arts and even gravestones were influenced by this revival. Marble, the building material of the ancient republics, became the stone of choice for grave markers, often drawn from quarries in nearby Tuckahoe. The imagery on the stones reflected this neo-classicism, particularly the urn, a symbol of death and mourning in the ancient world when cremation was common. Other iconographic elements of this pattern were the willow tree, a traditional symbol of grief in Europe, and the obelisk, which was used in both Rome and ancient Egypt. The emphasis also shifted from the deceased -- represented by the soul effigy -- to the bereaved family, with some stones depicting classically dressed figures in mourning, leaning against urns.

NPS Enclosing the Family Though it remained a traditional churchyard, St. Paul's was also affected by an important mid-19th century evolution called the rural cemetery movement. The rural cemetery, located just beyond the city, was a response to overcrowding of church burial yards in large cities of the northeast. Fences, such as the one seen in the lower right corner of the image, enclosed family plots as part of the rural cemetery movement. Inspired by romantic understanding of nature and art, as well as the melancholy theme of death, planners drew upon these themes to innovate burial ground design in England and France. These new cemeteries were supported through sales of private family plots which were carefully landscaped to create a picturesque setting in harmony with nature. Visitors were encouraged to stroll and picnic in these park-like settings. Some the earliest examples were Mt. Auburn, which opened outside Boston in 1831, and Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn, which was incorporated in 1838. A chief characteristic of the rural cemetery movement was the family tomb or the family plot, enclosed with decorative gates or fences. The wealth and status of the family could be declared more clearly in a private plot, and it is in this regard that St. Paul's took on characteristics of the rural cemetery movement. The first family tomb at St. Paul's was built in 1828 by the Drakes, prominent residents and one of the town's founding families in the 1660's. A row of underground family vaults was established around the time of the Civil War, and a series of enclosed family plots was developed toward the back of the yard by the late 19th century. A common feature of these plots is a large central monument -- usually an obelisk -- representing the unity and continuity of the family, with smaller individual stones for the deceased.

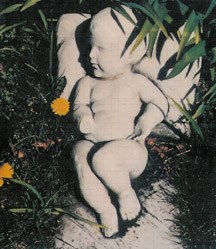

NPS Remembering the Children This tombstone for an infant is the only piece of detached sculpture in the St. Paul's cemetery. Early America was plagued by high rates of infant mortality, caused by contagious disease, sporadic food shortages, epidemics, and lack of medicines. The poignancy of the burial stones for young children in St. Paul's cemetery reflects the strong attachment of parents to their sons and daughters, even when early death was common. In the 18th century, parental affection was expressed in the choice of a rare type of stone (slate) an unusually shaped stone (two tablets for two children) and the special delicacy of a border design. In the more sentimental Victorian era, these sentiments are revealed in carvings of tiny blossoms and branches, figures of lambs or sleeping children, and in one case, a fully sculpted infant sleeping on a pillow. Poignant words chiseled into the stones created moving epitaphs that represent the grief of families who lost young children, but also the comfort they found in religious faith.

NPS Displaying Achievement This marble bench gravestone for landscape painter Edward Gay is one of the more unusual memorials in the cemetery. Greater individual membership in voluntary associations and increased wealth among certain family members had an important impact on gravestones at St. Paul's beginning in the mid-19th century. The Masonic symbol of the compass and T-square, with the G standing for God, is a fine example of this recognition of individual achievement or association. The Masonic emblem is carved into dozens of gravestones across the cemetery erected from the mid-19th to the 20th centuries. The Masons were an enormously influential group in 19th century America, and many of the nation's political and business leaders were Masons. Other symbols on tombstones reflected members in a variety of organizations that had special meaning to the deceased. Professional calling and talents such a medicine and art, were also memorialized. Crests and the introduction of very large monuments helped to emphasize a family's wealth and prominence.

NPS Return to Christian Symbolism This late 19th century marble monument features the Rustic Celtic cross, reflecting the introduction of traditional Christian symbolism in the cemetery. An ecumenical movement called the Oxford movement, or sometimes Anglo-Catholicism, caused changes in the Episcopal Church by the late 19th century, transforming the appearance of the St. Paul's graveyard. The movement, which sought to re-establish continuing between the Episcopal Church and medieval Christianity, led to a greater emphasis on ritual and mysticism. In the cemetery, this generated the more frequent employment of such Christian symbols as the cross, the angel and the lamb. An additional result of this movement was a change in the architecture of St. Paul's Church. When the belfry was rebuilt in 1887, the old weather vane at the top was replaced with a cross.

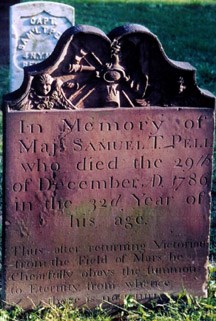

NPS Honoring the Soldiers A Trophy of Arms is chiseled into the top of this sandstone marker for Samuel T. Pell, an officer in the Continental army. St. Paul's is the final resting place of soldiers who fought in every war in American history from colonial times through World War II, mostly men who lived through the armed conflicts and died later as civilians. In the 5-acre space are interred men who, collectively, led the town militia in the 1720's, joined in the defeat the British at Yorktown in 1781, repaired ships during the Mexican-American War, withstood the Confederates' onslaught at Gettysburg in 1863, battled the Spanish on the island of Cuba in 1898, pushed back the German army on the Western front in the final days of World War I, and served on battleships in the Pacific Theater in World War II. These veterans, or their families, wanted posterity to recall their sacrifices, and many received government stones recording information about their service which are posted all across the burial yard at St. Paul's. The government financed burial stone originated after the Civil War, as part of the social responsibility of the Union to the veterans. The markers were originally available only for men killed in battle and buried in national cemeteries, but the government stone was extended to all veterans by an act of Congress in 1879. That law led to the introduction of the marble veterans' stone in private cemeteries, such as St. Paul's. The program was administered through the veterans' office of the War Department. Specifications for the stones were established nationally, but families of veterans contracted with local monument companies to create the burial stones. Government stones have remained an option for veterans since the Civil War, with periodic shifts in the style of the markers based on aesthetics and concerns about durability. |

Last updated: February 26, 2015