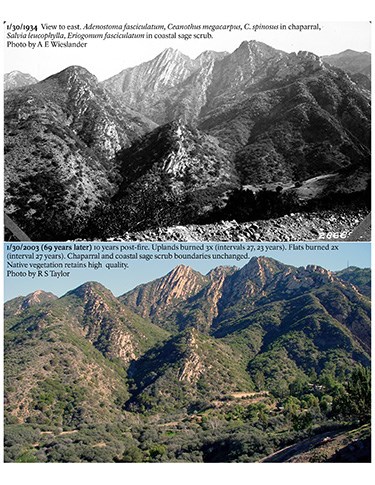

Coastal southern California shrublands are adapted to a fire regime of infrequent, intense, stand-replacing crown fires that usually occur in the fall. These fires are often sensationalized in the press and reported to have "destroyed" thousands of acres of wildlands. However, native shrublands are resilient to infrequent fires and have numerous traits that allow them to recover quickly. The first spring following a fire there is dramatic vegetation recovery on barren, blackened hillsides from resprouting shrubs and herbaceous perennials, germinating shrub seedlings, and an abundance of colorful native annuals. Within about 10 years at coastal sites and 20 years at inland sites, the canopy of the dominant shrubs begins to close and short lived fire-following annuals and perennials disappear and are present only in the soil seed bank. While chaparral is a fire adapted vegetation type, it is not useful to think of it as a fire-dependent ecosystem. This term implies a management need to provide fire that is lacking in an ecosystem. While a few chaparral species depend on fire to reproduce, such as the non-sprouting shrub species like bigpod ceanothus (Ceanothus megacarpus) and big-berry manzanita (Arctostaphylos glauca), most chaparral species in the Santa Monica Mountains are obligate sprouters and actually recruit in the fire-free intervals between fire. The current fire return interval of 28 years is far shorter than the estimated natural fire return interval of approximately 70-100 years. The ecological perturbations related to fire in the SMM's are not from an insufficient amount of fire required in a fire-dependent ecosystem, but from fire occurring at such a high frequency that it can exceed the ability of the ecosystem to recover normally.

Normal postfire recovery in chaparral is autosuccessional, that is, the same plant community will recover and reassemble after the fire, from in situ seedlings or resprouts.. Postfire recovery depends on spring-germinating seedlings and postfire resprouts surviving the summer dry season in the first year after fire, a period of 4-6 months without rain. Shrubs are classified by their method of recovery after fire which is associated with suites of morphological and physiological features related to drought tolerance. There are non-sprouters, species which are killed and regenerate only from seed; facultative sprouters, species which regenerate partly from seed and partly from a percentage of the plant population which resprouts; and obligate sprouters, which regenerate only from resprouts with no postfire seedling recruitment. Non-sprouting species that reproduce by seed after fires are shallowly rooted and tolerate high levels of drought stress; obligate sprouters are more deeply rooted and experience reduced drought stress by tapping into deep soil moisture supplies; faculatative sprouters are intermediate in their tolerance to drought stress. Understanding these relationships permits powerful ecological predictions about the trajectory of postfire vegetation recovery and the establishment of past vegetation patterns. Ecosystem threats from wildfire in the SMMNRA The park monitors recovery after wildfires and works with scientists to test predictions and detect potential ecosystem perturbations. There are a number of wildfire threats that concern the park. Short fire return intervals The non-sprouting shrub species in the SMMNRA are specialized elements of the flora and are of particular ecological and evolutionary interest. These species are the most sensitive to repeated fires at short intervals because there is inadequate time between fires to build up a sufficient seed bank to replace the population before the second fire. Non-sprouters can become locally extinct with fire intervals < 6years apart and significantly reduced at 12 years between fires.

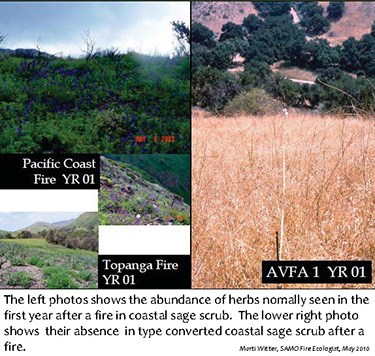

High fire frequency Even species less sensitive to repeated fires than non-sprouting shrubs begin to decline with repeated fires. There is cumulative mortality in all functional groups except the most vigorous resprouters, such as laurel sumac, that reduces shrub populations and the amount of shrub cover. Repeated fire disturbance favors the establishment of rapidly reproducing non-native annual grasses and forbs that have a higher ignition probability and produce cooler fires. Establishment of grasses and forbs in place of shrubs can lead to a postive feedback loop called the grass-fire cycle. The process of change from a native shrubland to a non-native dominated grassland is called type conversion. Type conversion leads not only to the loss of dominant shrubs, but also to the loss of the native annuals that contribute to rich postfire species diversity in the Santa Monica Mountains.

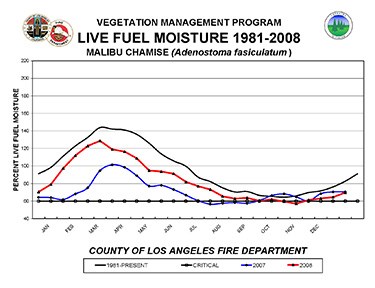

Climate change, fire and drought Southern California will experience among the most extreme shifts in climate in the United States in the 21st century. This is not so much because of the absolute magnitude of temperature and rainfall changes, but because of the enormous increase in variability expected in the climate system - increased severity and frequency of drought and increased severity of flooding. 2012 is the third year in the past decade of record low rainfall, so for the purposes of fire and planning, climate change has already arrived. The recent record low rainfall years have produced areas of chaparral dieback in the SMMNRA. Interestingly, this has occurred first in the most drought tolerant species, the obligate non-sprouting seeders, such as bigpod ceanothus. It is hypothesized that recent large fires in southern California have been fueled by drought induced dieback that has increased the rate of spread and spotting and the intensity of the fires.

When a drought year follows a fire year, then vegetation recovery is at risk from drought-induced mortality. Recent research in the SMMNRA has documented resprout mortality, an unappreciated possibility for postfire recovery in chaparral. Increased drought frequency from climate change, combined with a high fire frequency, increases the probability of fire and drought coinciding and the potential for large shifts in plant community composition. As temperatures rise and drought increases, live fuel moisture will be at critical levels earlier in the year and for longer periods of time, potentially extending the length of the fire season. Development and habitat modification Mature Mediterranean-type shrublands are both an important natural resource and a perfect fuel. In the SMMNRA there is extensive development that intermixes with wildlands. A major loss of habitat is from poorly designed fuel modification zones that remove native shrub habitat, but do not provide increased structure protection from wildfire loss. a. Install Class-A roofing materials. 3. Use noncombustible fencing materials. |

Last updated: June 7, 2022