NPS image Come with us on this e-walk back in time and learn about the processes responsible for building and shaping our park. Each 'virtual stop' along our e-walk tells an important part of Earth's history while illustrating how simple rocks relate to and play a crucial part in our world. Please note that all of these stops aren't marked, but most are located along the North Valley Trail in the park.

Site 1: The Dam at Lake 4The dam at Lake 4 was built into an exposure of rocks of the Wissahickon Formation of Precambrian Age - about 600 million years ago. The Earth’s climates and features during this time were vastly different from the present. North America and Africa were joined together in a supercontinent. Near the end of the era this supercontinent split, or rifted, and formed the continents of Africa and North America. Later, the same force that caused the continents to separate then caused them to move toward each other. A large volcano rose higher and higher off the east coast of North America. Deep in the Earth, a group of rocks known as the Wissahickon (Wis-suh-hik-un) formation formed as the ocean floor was driven beneath the eastern edge of the North American continent. If you were standing on top of these rocks, you can see the glittery “sparkles” of the mineral called mica, which is indicative of metamorphic rocks. You could also see large cracks or fractures throughout this rock exposure. With seasonal temperature changes; the fractures deepen and widen the cracks causing large blocks of rock to dislodge.

Site 2It is now 25-57 million years past the making of the Wissahickon rocks. The volcano has merged with North America, is a lot smaller, and its slopes are littered with ocean sediments. The vast continent of Africa crashes into the eastern coast of North America. The ground buckles, cracks, and folds while the Appalachian mountain range grows higher and higher to the west. Later, the volcano lies on its side like a toppled deck of cards. The volcanic rocks and ocean sediments along most of the east coast are then melted and recrystallized into a huge rock mass containing many different colored minerals and layers. Streams from the west then begin to deposit sediments that will eventually bury the area under a thick blanket of rock debris. The rocks laying in Quantico Creek are the metamorphosed remnants of the ocean sediments and volcanic flows. These rocks are part of the Chopawamsic (Chop-uh-wam-zik) formation. Chopawamsic rocks cover almost of the entire northern and western sections of the park. The pinkish lines running through the rock are quartz and formed as an addition to the rock at a much later date. Site 3This metamorphic rock is part of the Chopawamsic formation as well. Some of the minerals found in it are biotite, plagioclase, and quartz. The biotite is the black, shiny flakes seen upon close observation. Plagioclase is white to pink in color and often has white wispy threads running through it. The quartz found in this rock looks milky or clear.

Site 4: Fall Line ExposedOur next stop in time is the Jurassic period approximately 200 million years ago, when enormous dinosaurs roamed the land. To the east, a large fissure in the ground opens up that extends the length of the continent. Africa and North America separate for the second time. Meanwhile, streams and their origins in the Blue Ridge Mountains slowly erase all signs of the rift by continually eroding away the mountains and depositing sediments in the east. Sea level rises and the entire east coast is submerged beneath the ocean. Everything is buried beneath a thick layer of ocean sediments. Later, streams scour out the buried mountains and its valley to the east. Hidden beneath the layers of soil and leaves at this site is the boundary between the Piedmont and Coastal Plain. The cascading sections of the north branch of Quantico Creek reveal the presence of this boundary. The Fall Line is the name given to this boundary and extends from New Jersey to Georgia. The stream flows downstream through natural cracks or joint systems in the rock. During floods, the seemingly immovable rocks in this stream are rolled along the bed or bottom. This part of Quantico Creek is transporting large amounts of sediment as well as eroding the exposed rocks.

Site 5This site is a good example of present day geologic processes. All streams transport their load of sediment in three ways: in solution (dissolved load), in suspension (suspended load), and along the bottom of the channel (bed load). The nearby sediments of Quantico Creek consist of alluvium (mud, sand, and gravel) that has accumulated here during recent geologic time. If the loose sediments in this stream were to become cemented together, the result would be a sedimentary rock (Fig. 3). Notice the flaky, shiny specks of mica found in the sand along the trail. Only the harder, or more resistant rocks remain in the area after the wearing and tearing journey downstream. Site 6The whitish rock on the ground to the right of the marker post is quartz. This quartz probably crystallized from extremely hot solutions that traveled through the fractures of the surrounding Piedmont rock. Along this area of the trail are several exposures of white quartz from the Chopawamsic formation. Iron is present in these rocks and colors the quartz pink.

Site 7If an area is above sea level, the streams will erode in a downward direction – a process called down cutting. The creek at this site is no longer downcutting into the ground like it was further upstream. Evidence for this is the lack of steep V-shaped channels or banks. As the stream approaches sea level, it begins to bend back and forth in a series of meanders. Notice what happens to the nearby trees on the bank of the creek which are in the path of the shifting meander. Floodplain sediments are extremely rich in nutrients and minerals and make excellent farmland. Site 8The fine sedimentary particles in this stream may someday be buried, along with the accumulation of dead organic material from the forest, and be converted into a sedimentary rock. If there is enough heat and pressure at its depth underneath the ground, the organic material will undergo a chemical reaction and change into oil. This normally occurs at depths of 1,000 feet to 20,000 feet or more. If the temperature exceeds 100-150 degrees Celsius, then the oil will transform into natural gas. When searching for oil, geologists often look for the sandy deposits of an ancient river that ran through a forested area, such as the Quantico Creek.

Site 9Just as the mountains were weathered away by streams and transported eastward to form the Coastal Plain sediments, so has the waste rock present in this stream been transported away from its source – a mining operation. The sediments and pyrite found in this small feeder creek are from the waste (mined) rock in the nearby pyrite mine located to the south. Pyrite is greenish gold in color. Gravity and water action carry the pyrite and sediments to the larger Quantico Creek.

Site 10Running parallel to the left of the trail are the remnants of the Narrow Gauge Railroad, used to ship and transport the pyrite. The trail follows the flat, partially cleared areas where the rails were laid down. The Cabin Branch Pyrite Mine, which operated on the North Branch of Quantico Creek opened in 1889 and profited until the mine closed in 1920. Pyrite, also known as “fools gold,” was valued for its high sulfur content. Sulfur was used in the production of sulfuric acid, glass, soap, leather, fertilizer, metal cleaning products, and gunpowder.

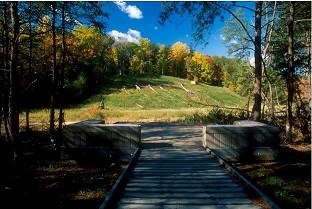

NPS photo Site 11The large hillside, west of the raised walkway, is the main area of the mine operation. The area is underlain by the metamorphic rocks of the Chopawamsic Formation. During the mine’s operation and after its closure, sulfuric acid leaked into the soil and the nearby stream from waste rock piles causing the soil and water to become too acidic to support life. Without any plants to hold the soil in place, erosion of the hill occurred rapidly and the stream became devoid of life. In 1998 the park worked with the Commonwealth of Virginia to stablize this mine site and to correct these harmful effects. This is the last stop on the main trail. As you walk back along the Pyrite Mine Road toward the Scenic Drive, take note of the rocks located along the hilltop and on the road. They are Coastal Plain sediments and formed as streams flowed into an ancient tidal area of the Atlantic Ocean. Additional Sites of Interest

Site E: Pine Grove Picnic Area, Laurel Loop and Birch Bluff TrailsThis area was once submerged beneath the ocean. Later it was home to dinosaurs. Some fossilized tree trunks have been found in these sediments. The many pebbles, cobbles, and sand grains were deposited here about 150 million years ago by streams and by the Atlantic Ocean. This area is part of the Coastal Plain province. These large, layered, grayish-green rocks located on both sides of the Laurel Loop trail are the result of a continental collision. When continents collide, the crust buckles and forms mountains. The intense heat and pressure cause the rocks in the surrounding region to change or metamorphose into the rocks you see now-Piedmont metamorphic rocks. The minerals and layering found in this exposure are typical traits of metamorphic rocks.

Site F: Birch Bluff TrailThe rocks lying exposed in Quantico Creek are greenstones. The greenish color of these rocks is caused by a mineral in the rock called epidote. These rocks formed originally as volcanic flows but were later metamorphosed into their present state during a continental collision. The highly polished surfaces of this outcrop develop as the scouring forces of sand and water smooth the rock into interesting shapes.

Site I: Algonquian TrailAs the stream erodes the ground here, many features become uncovered at the surface. This massive exposure of rock in the South Fork Quantico Creek is one such feature. Look closely, you can see the black shiny flakes of the mineral biotite. The continuous line of pink rock on the right side of the outcrop is called quartz. The quartz looks pink because it contains iron. On the bank, the glittery specks in the dust are called mica, and they are all that remains of rocks that once looked like the outcrop in the creek. |

Last updated: November 6, 2023