MENU

![]() Response to ANCSA, 1971-1973

Response to ANCSA, 1971-1973

|

The National Park Service and the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980: Administrative History Chapter Three: Response to ANCSA, 1971-1973 |

|

B. Identification of Study Areas, March-September 1972 (continued)

The National Park Service's Alaska Task Force participants arrived in Anchorage for orientation meetings on June 5-7. [52] By June 9, two teams were in the field, while the other teams worked in Anchorage, reviewing existing literature and maps. The next week, they alternated. [53] Given the limited time frame, it is obvious that on-site analysis could not be much more than cursory and that the recommendations due in July were based to a large extent on information gathered from previous studies.

After weeks of virtually around the clock effort the Service recommended that Secretary Morton withdraw for study for potential additions to the National Park System eleven areas totaling 48,945,800 acres:

| Noatak | 8,357,000 |

| Gates of the Arctic | 11,040,220 |

| Great Kobuk Sand Dunes | 925,400 |

| Chukchi/Imuruk (Imuruk Lava Fields) | 2,150,900 |

| Tanana Hills-Yukon River | 2,533,900 |

| Mount McKinley N.P. additions (2) | 3,687,600 |

| Katmai N.M. additions (2) | 1,584,740 |

| Lake Clark Pass | 4,462,920 |

| Kenai Fjords | 95,400 |

| Wrangell-Saint Elias | 13,368, 600 |

| Aniakchak Crater | 740,240 |

The Service noted, additionally, that large areas of the state should be studied to determine the extent of archeological, historical, and paleontological resources. It recommended that some means of safeguarding those resources be undertaken, either by extending to them the protection of the federal or state antiquities act, or by encouraging the Native associations to protect them along the lines adopted by other Native groups such as the Navajo tribe of Arizona and New Mexico. [54]

Among the major changes recommended were the transfer of 4,368,000 acres from d-1 to d-2 status in the eastern Wrangell mountains, and deletion of Mt. Veniaminof, Nogabahara Sand Dunes, and Chukchi withdrawal areas. In the Noatak, recommended deletions of 388,900 acres in Kikmikso Mountain and the south Waring Mountains and along the Redstone Mountains were more than balanced by the recommended addition of 411,800 acres from open lands in the DeLong Mountains and Kotlik Lagoons. The latter, which included lands of potential archeological values along the coast, would become an important part of the Cape Krusenstern proposal when that area was separated from the Noatak. [55]

The NPS Alaska Task Force recommended, additionally, that three units totalling 95,400 acres of the 139,600-acre withdrawal in the Kenai Fjords area be included as an NPS study area. Kenai Fjords had been included in the Service's interest areas earlier, but had been dropped in an effort to reach the 80,000,000-acre d-2 limitation. It was included in the March d-2 withdrawals as part of the BSF&W's Aialik withdrawal area. [56]

The Task Force recommended that, whenever possible, Secretary Morton include in his September withdrawals, boundaries "which encompass complete watersheds, sufficient intact habitats, units of geological importance." [57] Because the study teams were unable to make more than cursory fly-over inspections of the areas at this time, mistakes understandably were made. At Gates of the Arctic, for example, the study team failed to include the Upper Ambler, Shungnak, and Kogoluktuk rivers on the western part of the proposal. [58] Nevertheless, along with the areas recommended by other federal agencies and existing park areas, the eleven NPS areas recommended for final d-2 withdrawals would, according to Francis S.L. Williamson, "make available in perpetuity to the American people [an] adequate representation of the magnificence, grandeur and biological uniqueness of Alaska." The recreational and esthetic values of the total resource, concluded Williamson, "are boundless and collectively represent a broad cross section of all those features of our natural heritage that the NPS was established to provide." [59]

Additionally, the Task Force recommended joint studies with the state of Alaska and Native groups for future land use of certain lands adjoining the proposed d-2 withdrawals. These areas—the nine townships of pending state selections that included portions of the John River Valley and Wild Lake immediately south of the Gates of the Arctic withdrawal area, for example—were lands whose use would have a significant impact on the future parklands. Elsewhere, the Service recommended certain land use controls for d-1 lands adjoining the d-2 withdrawals. [60] These recommendations were the first hint of a concept that would be amplified, later, as areas of ecological concern.

As was the case with the March withdrawals, Secretary Morton's final 17(d)(2) withdrawal would not be based solely on resource values as defined by bureau experts, but, rather, would be the result of a careful weighing of competing interests. As the Service's proposals moved through the various levels of the department, the Secretary heard from other Interior agencies—the USGS and BLM presented reports, for example. On August 4 Dr. Edgar Wayburn of the Sierra Club wrote Secretary Morton, offering suggestions regarding the approach he might take, and recommended the withdrawal of thirteen areas totalling some 84,000,000 acres. [61]

By early August, too, the Forest Service, having completed a review of 127,000,000 acres, presented its recommendations to Secretary Morton. Commenting on the proposals of the Interior Department agencies, Forest Service officials called for an alternative "balanced system" that would provide for a "mixture of multiple use lands as well as lands of high scenic and scientific value and units of international importance to wildlife." A balanced system, agency officials concluded, would include 32,400,000 acres for potential units of the National Park System, 32,300,000 acres for refuges, 7,000,000 for wild and scenic rivers, and 41,700,000 acres for national forests, a considerable portion of which would be in interior Alaska. Subtracting 35,700,000 acres of overlaps (19,400,000 acres of proposed forest land conflicted with NPS proposals), the total acreage in the Forest Service package was 80,000,000 acres. [62]

By August 16, following briefings by Native groups as well as departmental review, the combined study area acreages stood at 75,940,000 acres. NPS areas totalled 41,599,140, BSF&W's were 42,641,833, with 1,000,000 more for wild and scenic rivers and 1,500,000 for national forests. The figure included overlapping land amounting to 11,620,340 acres. [63]

According to Secretary Morton, however, the Joint Federal-State Land Use Planning Commission provided the most influential advice in the decision-making process leading to the final 17(d)(2) withdrawals on September 13. [64] The commission itself did not meet until July 31—Secretary Morton had not announced his appointees until July 14. [65]

By April, however, it had been decided that the Northern Alaska Planning Team, an interagency, multi-disciplinary task force of twenty-five specialists from various state and federal agencies, would be assigned to the commission as its resource planning team. [66] Throughout the summer, the resource planning team studied the March withdrawals and conflicting claims by state and Native groups to make recommendations to the full commission.

On August 9-11 the commission heard from representatives of the federal agencies involved in d-2 implementation, as well as state, Natives, and Alaska conservationists. On August 16 four members of the commission met with Secretary Morton in Washington, D.C. to present its recommendations. [67]

The make-up of the commission, both as mandated by ANCSA and in appointees themselves, seemed to promise a balanced approach intended by the legislation. As constituted the commission represented a cross-section of the various interest groups involved—Celia Hunter, a long-time Alaskan conservationist and Charles Herbert, a strong supporter of Alaska mining interests were on the panel, for example. [68] The commission had the responsibility of balancing all competing interests. When its recommendations were made public, however, it seemed to reflect, from the perspective of NPS planners at least, a shift toward multiple-use and joint federal-state management from dominant use as represented in the National Park System. [69]

The commission made no specific recommendations regarding management or boundaries of areas. They had examined areas of state-federal conflict, however, and made specific recommendations on thirteen. In addition, they recommended several alternative policy actions. Secretary Morton could shift the entire 80,000,000 acres of d-2 lands to d-1, with some restrictions on taking of minerals, or he could transfer any portion of the d-2 lands in conflict with state or Native designations (15,000,000 acres) to d-1 status. [70]

Overall, the effect on the Service's d-2 withdrawal recommendations was not as great as many feared it would be. However, the Commission's recommendations in at least three areas—Gates of the Arctic, Mount McKinley and Lake Clark—would have an impact when they were included in an out-of-court agreement that resolved the lawsuit filed by the state of Alaska in April 1972 over conflict between state selections and Secretary Morton's March withdrawals. In a September 2 agreement with Secretary Morton the state agreed to drop its lawsuit and its claim to 42,000,000 acres of pre-selected land in return for immediate selection rights to lands on the south slope of the Brooks Range, south of Mount McKinley National Park, and in the central part of the Brooks Range. An additional clause that would bulk larger later, opened lands along Antler Bay, Cape Kumlik, and Aniakchak Bay in the Park Service's Aniakchak interest area to sport hunting. [71]

On September 13, 1972, Secretary Morton announced the final 17(d)(2) withdrawal of twenty-two areas totalling 79,300,000 acres of land in Alaska for study for possible addition to the National Park, Forest, Wildlife Refuge, and Wild and Scenic Rivers systems. [72] Actually, insofar as the Park Service was concerned, the September 2 agreement had predetermined the nature of the September withdrawals. There were no surprises in Secretary Morton's withdrawals.

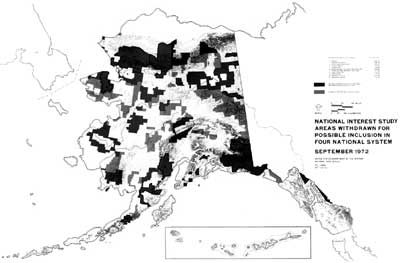

National Interest Study Areas Withdrawn for Possible

Inclusion in Four National Systems, September 1972. (Boundaries

Approximate)

(click on map for larger size)

In the decision-making process that led to the September withdrawals, the Park Service lost 600,000 acres of critical caribou range in the recommended additions to Mount McKinley National Park, and important access routes into Mount McKinley (Chelatna Lake/Sunflower Basin) and Gates of the Arctic (Alatna and John Rivers). Clark proposal was severely compromised, and the Tanana hills portion of the Tanana Hills-Yukon River area had been eliminated. Much of the proposed transfer of d-1 lands to d-2 status in Wrangell-St. Elias had been deleted. [73]

NPS Alaska Task Force planners watched apprehensively the process leading to the September withdrawals, writing in August, for example, "we got all the rock and ice we asked for" at Mount McKinley, or somewhat sarcastically observing, as Paul Fritz did, that Wrangell-Saint Elias be named "The Great Glacier National Park." [74] Despite their concerns, the Park Service received most of the land Alaska task force planners believed necessary for study as potential parklands:

| Acreage | ||

| Noatak | 7,874,700 | |

| Gates of the Arctic | 9,388,100 | |

| Great Kobuk Sand Dunes | 1,454,400 | |

| Imuruk | 2,150,900 | |

| Yukon River | 1,233,660 | |

| Mt. McKinley NP additions | 2,996,640 | |

| Katmai NM additions | 1,411,900 | |

| Lake Clark Pass | 3,725,620 | |

| Kenai Fjords | 95,400 | |

| Wrangell-St. Elias | 10,613,540 | |

| Aniakchak Crater | 740,200 | |

| Total | 41,685,060 | [75] |

Chapter Three continues with...

Preparation of Legislative Recommendations

Top

Top

Last Modified: Tues, Jan 9 2001 10:08 am PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/williss/adhi3b-1.htm

![]()