| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

THE RIGHT TO FIGHT: African-American Marines in World War II by Bernard C. Nalty Starting from Scratch The training program at Montford Point, which signaled the first appearance of blacks in Marine uniforms since the Revolutionary War, began with boot camp and had as its ultimate objective the creation of a composite defense battalion. This combat unit would be racially segregated, commanded by white officers, and with an initial complement of white noncommissioned officers, who would serve only until black replacements became available. Colonel Woods had to start from scratch, with no cadre of experienced African-Americans except for a handful with prior service in the Army or Navy. When boot training began, the colonel commanded both the camp itself and the 51st Defense Battalion (Composite) being formed there. Lieutenant Colonel Theodore A. Holdahl — an enlisted veteran of World War I who served as an officer in the Far East and Central America — had charge of recruit training. Some two dozen white officers, a number of them recently commissioned second lieutenants like Bobby Troup, and 90 white enlisted Marines, directed the training. The enlisted men formed the Special Enlisted Staff, which initially carried out assignments that varied from clerk or typist to drill instructor. The Marine Corps screened the Special Enlisted Staff to exclude anyone opposed to the presence of blacks in the ranks. One of the Montford Point Marines suggested that, in the normal pressures of boot camp, a break down in the screening process could have doomed the program, for racial hostility would have reinforced the usual harassment visited on every recruit, white or black. "We would all have left the first week," he joked. "Some of us, probably, the first night."

In keeping with Marine Corps policy, Woods and Holdahl had to replace the whites of the Special Enlisted Staff with black noncommissioned officers as rapidly as possible. The command structure at Montford Point tried to identify the best of the African-American recruits and place them on a fast track to positions of responsibility in boot camp and in the battalion itself. The general classification test, administered as a part of the initial processing, grouped those who took the test into five categories, with the highest scores in Category I, and afforded one tool for predicting the ability of the new Marines. Unfortunately, those black Marines who administered the test and interpreted the results were themselves on-the-job trainees. Consequently, the test results could at times prove misleading, with college graduates sometimes showing up in Categories IV or even V. Drill instructors, initially whites with varying experience in the Marine Corps, had to rely on their own powers of observation to determine which of the African-American recruits had the aptitude to exercise effective leadership and master the necessary technology. Formal tests, written or oral, provided a final winnowing of the candidates. The first promotions, to private first class, took place early in November 1942, a month be fore the men selected to sew on their single stripe had completed boot camp.

The problem of classifying recruits demonstrated that the Montford Point Camp required skilled administrators. Creating an administrative infrastructure proved difficult, for the comparatively few volunteers who stepped forward in the summer and fall of 1942 included few clerks and typists. Enough African-American recruits would have to learn the mysteries of Marine Corps administration to fill the necessary billets, but racial segregation prevented them from taking courses alongside whites. For the present, white instructors would teach administrative subjects at Montford Point, until black Marines could master the skills and pass them along. When tackling the more complex subjects, like optical fire control or radar, the African Americans attended courses offered by the Army at nearby Camp Davis, North Carolina, and elsewhere. Lacking a cadre of black veterans, the Marine Corps had to advance the best of the African-American recruits into the ranks of noncommissioned officers so as to achieve the goal of a segregated defense battalion commanded by white officers but with no white enlisted men in any capacity. The promotion of black Marines depended on ability, as revealed by the initial classification tests, ratings from superiors, the results of formal examinations, and the existence of vacancies that would not violate policy by placing a black Marine in charge of whites. As the number of African-American Marines increased and training activity accelerated, some of the recently promoted privates first class, corporals, and sergeants became assistant drill instructors at the Montford Point boot camp, replaced the white drill instructors, or joined the defense battalion when it began taking shape. The rapid expansion of the noncommissioned ranks thrust many of the newly promoted black Marines into sink-or-swim assignments in which they not only kept their heads above water but made rapid progress against the current.

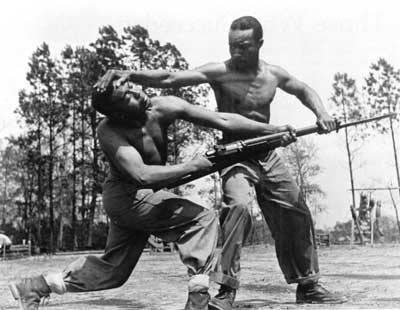

A few of the black volunteers be sides Gilbert Johnson had previous military experience; others had special ability or the potential for leadership. John T. Pridgen, for instance, had served in the 10th Cavalry before the war, and George A. Jackson had been an officer in the peacetime Army reserve. At a time when few whites and fewer blacks held degrees, the Montford Point Marines included several college graduates, among them Charles F. Anderson and Charles W. Simmons. The talents of Arvin L. "Tony" Ghazlo proved as valuable as they were rare, for as a civilian he had given lessons in jujitsu. With the help of another black Marine, Ernest "Judo" Jones, Ghazlo taught unarmed combat at Montford Point. Men like these replaced members of the Special Enlisted Staff in the training process, a transition all but completed by the end of April 1943, and became noncommissioned officers in the 51st Defense Battalion and the other units formed from the tide of draftees.

Thanks to the use of the Selective Service System as the normal source of recruits, the nature of the program at Montford Point was changing. A single defense battalion could not absorb the influx of blacks into the Marine Corps. Consequently, Secretary of the Navy Knox authorized a Marine Corps Messman Branch and the first of 63 combat support companies — either depot or ammunition units — as well as a second defense battalion, the 52d. An expansion of the Montford Point Camp began, as the Marine Corps prepared to house another thousand blacks there. The Headquarters and Service Company, Montford Point Camp, came into existence on 11 March 1943, and at the same time, the 51st Defense Battalion (Composite) provided the nucleus for the Headquarters Company, Recruit Depot Battalion. Colonel Woods retained command of the camp, entrusting the defense battalion to Lieutenant Colonel W. Bayard Onley, a graduate of the Naval Academy whose most recent assignment had been Regimental Executive Officer, 23d Marines. Lieutenant Colonel Holdahl continued to exercise control over boot training as commander of the new recruit battalion. On 1 April, Captain Albert O. Madden, a veteran of World War I who, as a civilian, had operated restaurants in Albany, New York, took command of the new Messman Branch Battalion; on the 13th, when the Messman Branch became the Stewards' Branch, the name of Madden's battalion changed to reflect the redesignation. The growth of the Montford Point operation required additional housekeeping support, much of it obtained from the rifle company of the 51st Defense Battalion, after a modified table of organization disbanded the infantry unit in the summer of 1943.

|