| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

FREE A MARINE TO FIGHT: Women Marines in World War II by Colonel Mary V Stremlow, USMCR (Ret) Overseas Since the Women's Army Corps began as an auxiliary, it was less strictly regulated than the other women's services. Consequently, WACs served in all theaters of war including the Southwest Pacific Area, the Southeast Asia Command, the China-Burma-India Theater, the China Theater, and the Middle East Theater, as well as in Europe, Africa, Hawaii, Alaska, New Caledonia, Puerto Rico, and several smaller sites. While some members of Congress, uncomfortable about American women so close to combat, argued for restrictions, there were military men like Marine Lieutenant General Holland M. Smith who insisted that women Marines could be used at Pearl Harbor to release men for combat. His view was shared by Navy Secretary James V. Forrestal, who told Congress that an estimated 5,000 naval servicewomen were needed in Hawaii. The outcome was new legislation, Public Law 441, 78th Congress, signed on 27 September 1944 which amended Section 504, Public Law 689, 77th Congress, 30 July 1942 by providing that:

Colonel Streeter, anticipating the new policy, was concerned about choosing mature, stable women for duty outside the continental United States. So, she went to see WAC Director Colonel Hobby, and said, "Look, Oveta, what did you find was the best way of selecting your people to go overseas?" By her own admission, going straight to Colonel Hobby was ". . . not exactly according to Hoyle," but ". . . it was certainly sensible and nobody fussed about it." Colonel Hobby offered simple advice: "A person who's had a good record in this country is likely to have a good record abroad, and a person who's had disciplinary problems in this country, or whose health wasn't good, we wouldn't send abroad. Sometimes you sent more mature ones than the newest enlistees." With this in mind, the Marine Corps laid out the criteria for selecting volunteers for duty in Hawaii: satisfactory record for a period of six months military service subsequent to completion of recruit or specialist training; motivation, the desire to do a good job, rather than excitement or hope of being near someone they cared about; good health; stable personality; sufficient skill to fill one of the billets for which Women Reservists had been requested; and age. Not having been a significant factor for success in the WACs, age was not specified, but since the minimum tour was to be two years with little hope for leave, the health and status of dependents and close family members was considered.

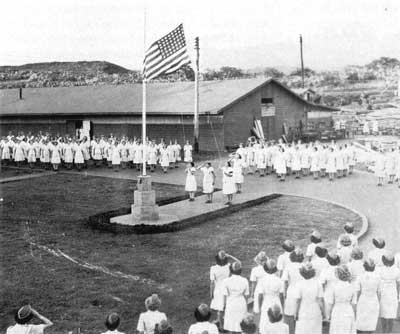

This settled, in October 1944, Colonel Streeter and Major Marion B. Dryden flew to Hawaii to prepare for the arrival of the women and most of all to inspect the proposed living arrangements. Major Dryden, the senior woman officer serving in aviation, accompanied the Director because half the women were to be stationed at the Marine Corps Air Station, Ewa. There was no shortage of volunteers and on 2 December an advance party of four officers — Major Marion Wing, commanding officer; First Lieutenant Dorothy C. McGinnis adjutant; First Lieutenant Ruby V. Bishop, battalion quartermaster; and Second Lieutenant Pearl M. Martin, recreation officer — flew to Hawaii to make preliminary arrangements at Pearl Harbor. Not long after, they were followed by the advance party for Ewa, Captain Helen N. Crean, commanding officer; First Lieutenant Caroline J. Ransom, post exchange officer; Second Lieutenant Bertha K. Ballard, mess officer, along with Second Lieutenant Constance M. Berkolz, mess officer for Pearl Harbor. Meanwhile, a staging area was established at the Marine Corps Base, San Diego, where the women underwent a short but intense physical conditioning course that included strapping on a 10-pound pack to practice ascending and descending cargo nets and jumping into the water from shipboard. In the classroom, they learned about the people of Hawaii, how to recognize Allied insignia, shipboard procedures, and the importance of safeguarding military information. On 25 January 1945, with Captain Marna V. Brady, officer-in-charge, the first contingent of five WR officers and 160 enlisted women, with blanket rolls on their backs, marched up the gangplank of the S.S. Matsonia to sail from San Francisco to Hawaii. Their shipmates were a mixed lot of male Marines, sailors, WAVES, military wives, and ex-POWs, and because of the lopsided ratio of men to women, the WRs were restricted to a few crowded spaces on board ship. Two days out to sea, they changed to summer service uniform, and on 28 January, they disembarked in Honolulu as the Pearl Harbor Marine Barracks Band played "The Marine's Hymn," the "March of the Women Marines," and "Aloha Oe." The WAVES went ashore first — dressed in their best uniform. Then came the WRs — astonished that their no-nonsense appearance in dungarees, boondockers, and overseas caps seemed to please the crowd of curious Marines who had gathered to look them over and welcome them to Hawaii. The majority was quartered in barracks recently vacated by the Seabees at the Moanalua Ridge Area adjacent to the Marine Corps Sixth Base Depot and Camp Catlin. The large, wooden, airy barracks were already very comfortable, but needed modifications for female occupants, so a small number of Seabees remained behind to do some reconditioning. Major Wing, the commanding officer, ". . . had a fine way of treating men" according to Colonel Streeter.

In Hawaii, the women worked much the same as in the States, with most assigned to clerical jobs. More than a third of the women at Ewa came from the Marine Corps Air Station, Cherry Point, and lost no time before picking up their tools and working on the planes.

At Pearl Harbor, the WRs ran the motor transport section, serving nearly 16,000 persons a month. Scheduled around the clock and with a perfect safety record, they maneuvered the mountainous roads of Hawaii in liberty buses, jeeps, and all types of trucks carrying mail, people, ammunition, and garbage. Marines easily became accustomed to the sight of women drivers, but never quite got used to grease-covered female mechanics working under the hood or chassis of two-and-a-half-ton trucks. The Deputy Commander, Headquarters, Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, gave the WRs high marks for their efficiency, attitude, and enthusiasm, and reported: "The work of Women's Reserve personnel trained in Marine Corps Specialist Schools has measured up to the standard of performance required of men in specialists' assignments, such as Quartermaster Supply Men, Radio Operators, Radio Repairmen, Financial Clerks, Drivers, and Mechanics." He went on, however, to criticize the typical women's command structure and recommended that, in the future, the administration of the Women's Reserve be handled by the unit to which the women are attached for duty. It was a widespread complaint, already voiced by Colonel Streeter and destined to be repeated by Marines — men and women — for nearly 30 years until the all-female units were finally disbanded in the mid-1970s. Just before she left the Corps, Colonel Streeter expressed some reservation about the wisdom of sending WRs to Hawaii — despite their substantial contribution. After the initial enthusiasm, interest waned, boyfriends were opposed to having their girls go so far away, especially where they were vastly outnumbered, and parents were put off by the length of the tour. There was uneasiness among the women caused by the shifting pronouncements from Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, about how many WRs they really needed, and at the same time, it was becoming clear that victory over Germany was imminent. Fewer women volunteered for overseas and the Director was disappointed.

By the summer of 1945, there were 21 officers and 366 enlisted Women Reservists at Ewa, and 34 officers and 580 enlisted women in the Women's Reserve Battalion, Marine Garrison Forces, 14th Naval District. Some stayed to process the men being shipped through Hawaii on their way home for demobilization, but they were all back in the States by January. Because women serving overseas accumulated credits for discharge at the rate of two per month, compared to one per month for those in the United States, most were eligible for discharge soon after V-J Day.

|