| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

INFAMOUS DAY: Marines at Pearl Harbor by Robert J. Cressman and J. Michael Wenger They Caught Us Flat-Footed (continued) Elsewhere in the Ewa Beach community, Mrs. Charles S. Barker, Jr., wife of Master Technical Sergeant Barker, the chief clerk in MAG-21's operations office, hear the noise and asked: "What's all the shooting?" Barker, clad only in beach shorts, looked out his front door, saw and heard a plane fly by at low altitude, and then saw splashes along the shoreline from strafing planes marked with red hinomaru. Running out to turn off the water hose in his front yard, and seeing a small explosion nearby (probably an antiaircraft shell from the direction of Pearl), Barker had seen enough. He left his wife and baby with his neighbors, and set out for Ewa.

The strafers who singled out cars moving along the roads that led to Ewa proved no respecter of persons. MAG-21's commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Claude A. "Sheriff" Larkin, en route from Honolulu, was about a mile from Ewa in his 1930 Plymouth when a Zero shot at him. He momentarily abandoned the car for the relative sanctuary of a nearby ditch, not even bothering to turn off the engine, and then, as the strafer roared out of sight, sprinted back to the vehicle, jumped back in, and sped on. He reached his destination at 0805 — just in time to be machine gunned again by one of Admiral Nagumo's fighters. Soon thereafter, Larkin's good fortune at remaining unwounded amidst the attack ran out, as he suffered several penetrating wounds, the most painful of which included one on the top of the middle finger of his left hand and another on the front of his lower left leg just above the top of his shoe. Refusing immediate medical attention, though, Larkin continued to direct the defense of Ewa Field. Pilots and ground crewmen alike rushed out onto the mat to try to save their planes from certain destruction. At least a few pilots intended to get airborne, but could not because most of their aircraft were either afire or riddled beyond any hope of immediate use. Captain Milo G. Haines of VMF-211 sought safety behind a tractor, he and the machine's driver taking shelter on the side opposite to the strafers. Another Zero came in from another angle, however, and strafed them from that direction. Spraying bullets clipped off Haines' necktie just beneath his chin. Then, as a momentarily relieved Haines put his right hand at the back of his head a bullet lacerated his right little finger and a part of his scalp.

In the midst of the confusion, an excited three-year old Hank Anglin innocently took advantage of his father's distraction with the battle and wandered toward the mat. All of the noise seemed like a lot of fun. Sergeant Anglin ran after his son, got him to the ground, and, shielding him with his own body, crawled some 35 yards, little puffs of dirt coming near them at times. As they clambered inside the radio trailer to get out of harm's way, a bullet made a hole above the door. Moving back to the photo tent, the elder Anglin put his son under a wooden bench. As he set about gathering his camera gear to take pictures of the action, a bullet went through his left arm. Deprived of the use of that arm for a time, Anglin returned to the bench under which his son still crouched obediently, to see little Hank point to a spent bullet on the floor and hear him warn: "Don't touch that, daddy, it's hot."

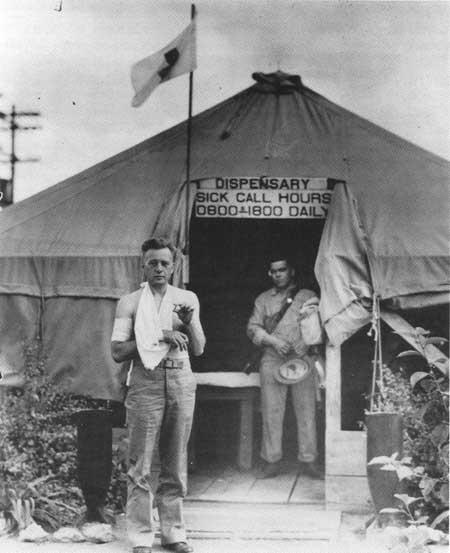

Private First Class James W. Mann, the driver assigned to Ewa's 1938 Ford ambulance, had been refueling the vehicle when the attack began. When Lieutenant Thomas L. Allman, Medical Corps, USN, the group medical officer, saw the first planes break into flames, he ordered Mann to take the ambulance to the flight line. Accompanied by Pharmacist's Mate 2d Class Orin D. Smith, a corpsman from sick bay, they sped off. The Japanese planes seemed to be attracted to the bright red crosses on the ambulance, however, and halted its progress near the mooring mast. Realizing that they were under attack, Mann floored the brake pedal and the Ford screeched to a halt. Rather than leave the vehicle for a safer area, Mann and Smith crawled underneath it so that they could continue their mission as quickly as possible. The strafing, however, continued unabated. Ironically, the first casualty Mann had to collect was the man lying prone beside him. Orin Smith felt a searing pain as one of the Japanese 7.7-millimeter rounds found its mark in the fleshy part of his left calf. Seeing that the corpsman had been hurt, Mann assisted him out from under the vehicle and up into the cab. Despite continued strafing that shot out four tires, Mann pressed doggedly ahead and delivered the wounded Smith to sick bay.

After seeing that the corpsman's bleeding was stopped and the painful wound was cleaned and dressed, Private First Class Mann sprinted to his own tent. Grabbing his rifle, he then returned to the battered ambulance and, shot-out tires flopping, drove toward Ewa's garage. There, Master Technical Sergeant Lawrence R. Darner directed his men to replace the damaged tires with those from a mobile water purifier. Meanwhile, Smith resumed his duties as a member of the dressing station crew. Also watching the smoke beginning to billow skyward was Sergeant Duane W. Shaw, USMCR, the driver of the station fire truck. Normally, during off-duty hours, the truck sat parked a quarter-mile from the landing area. Shaw, figuring that it was his job to put out the fires, climbed into the fire engine and set off. Unfortunately, like Private First Class Mann's ambulance, Sergeant Shaw's bright red engine moving across the embattled camp soon attracted strafing Zeroes. Unfazed by the enemy fire that perforated his vehicle in several places, he drove doggedly toward the flight line until another Zero shot out his tires. Only then pausing to make a hasty estimate of the situation, he reasoned that with the fire truck at least temporarily out of service he would have to do something else. Jumping down from the cab, he soon got himself a rifle and some ammunition. Then, he set out for the flight line. If he could not put out fires, he could at least do some firing of his own at the men who caused them. With the parking area cloaked in black smoke, Japanese fighter pilots shifted their efforts to the planes either out for repairs in the rear areas or to the utility planes parked north of the intersection of the main runways. Inside ten minutes' time, machine gun fire likewise transformed many of those planes into flaming wreckage. Firing only small arms and rifles in the opening stages, the Marines fought back against Kaga's fighters as best they could, with almost reckless heroism. Lieutenant Shiga remembered one particular Leatherneck who, oblivious to the machine gun fire striking the ground around him and kicking up dirt, stood transfixed, emptying his sidearm at Shiga's Zero as it roared past. years later, Shiga would describe that lone, defiant, and unknown Marine as the bravest American he had ever met. A tragic drama, however, soon unfolded amidst the Japanese attack. One Marine, Sergeant William E. Lutschan, Jr., USMCR, a truck driver, had been "under suspicion" of espionage and he was ordered placed under arrest. In the exchange of gunfire that followed his resisting being taken into custody, though, he was shot dead. With that one exception, the Marines at Ewa Field had fought back to a man.

As if Akagi's and Kaga's fighters had not sown enough destruction on Ewa, one division of Zeroes from Soryu and one from Hiryu arrived on the scene, fresh from laying waste to many of the planes at Wheeler Field. This second group of fighter pilots went about their work with the same deadly precision exhibited at Wheeler only minutes before. The raid caught master Technical Sergeant Darner's crew in the middle of changing the tires on the station's ambulance. Private First Class Mann, who by that point had managed to obtain some ammunition for his rifle, dropped down with the rest of the Marines at the garage and fired at the attacking fighters as they streaked by. Lieutenant Kiyokuma Okajima led his six fighters down through the rolling smoke, executing strafing attacks until ground fire holed the forward fuel tank of his wingman, Petty Officer 1st Class Kazuo Muranaka. When Okajima discovered the damage to Muranaka's plane, he decided that his men had pressed their luck far enough, and began to assemble his unit and shepherd them toward the rendezvous area some 10 miles west of Kaena Point. The retiring Japanese in all likelihood then spotted incoming planes from Enterprise (CV-6), that had been launched at 0618 to scout 150 miles ahead of the ship in nine two-plane sections. Their planned flight path to Pearl was to take many of them over Ewa Mooring Mast Field, where some would encounter Japanese aircraft. Meanwhile, back at Ewa, after what must have seemed an eternity, the Zeroes of the first wave at last wheeled away toward their rendezvous point. Having made a shambles of the Marine air base, Japanese pilots claimed the destruction of 60 aircraft on the ground: Akagi's airmen accounted for 11, Kaga's 15, Soryu's 12, and Hiryu's 22. Their figures were not too far off the mark, for 47 aircraft of all types had been parked at the field at the beginning of the onslaught, 33 of which had been fully operational. Although the Japanese had wreaked havoc upon MAG-21's complement of planes, the group's casualties seemed miraculously light. Apparently, the enemy fighter pilots in the first wave maintained a fairly high degree of discipline, eschewing attacks on people and concentrating their attacks on machines. Many of Ewa's Marines, however, had parked their cars near the center of the station. By the time the Japanese departed, the parking lot resembled a junk yard of mangled automobiles of various makes and models. Overcoming the initial shock of the first strafing attack, Ewa's Marines took stock of their situation. As soon as the last of Itaya's and Shiga's Zeroes had departed, Marines went out and manned stations with rifles and .30-caliber machine guns taken from damaged aircraft and from the squadron ordnance rooms. Technical Sergeant William G. Turnage, an armorer, supervised the setting up of the free machine guns. Technical Sergeant Anglin, meanwhile, took his little boy to the guard house, where a woman motorist agreed to drive Hank home to his mother. As it would turn out, that reunion was not to be accomplished until much later that day, "inasmuch as the distraught mother had already left home to look for her son." Master Technical Sergeant Emil S. Peters, a veteran of action in Nicaragua, had, during the first attack, reported to the central ordnance tent to lend a hand in manning a gun. By the time he arrived there, however, there were none left to man. Then he saw a Douglas SBD-2, one of two spares assigned to VMSB-232, parked behind the squadron's tents. Enlisting the aid of Private William G. Turner, VMSB-231's squadron clerk, Peters ran over to the ex-Lexington machine that still bore her USN markings, 2-B-6, pulled the after canopy forward, and clambered in the after cockpit, stepping hard on the foot pedal to unship the free .30-caliber Browning from its housing in the after fuselage, and then locking it in place. Turner, having obtained a supply of belted ammunition, took his place on the wing as Peter's assistant.

|