| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

INFAMOUS DAY: Marines at Pearl Harbor by Robert J. Cressman and J. Michael Wenger Suddenly Hurled into War (continued) Shapley and Corporal Nightingale made their way across the ship between Turret III and Turret IV, where Shapley stopped to talk with Lieutenant Commander Samuel G. Fuqua, Arizona's first lieutenant and, by that point, the ship's senior officer on board. Fuqua, who appeared "exceptionally clam," as he helped men over the side, listened as Shapley told him that it appeared that a bomb had gone down the stack and triggered the explosion that doomed the ship. Since fighting the massive fires consuming the ship was a hopeless task, Fuqua told the Marine that he had ordered Arizona abandoned. Fuqua, the first man Sergeant Baker encountered on the quarterdeck, proved an inspiration. "His calmness gave me courage," Baker later declared, "and I looked around to see if I could help." Fuqua, however, ordered him over the side, too. Baker complied.

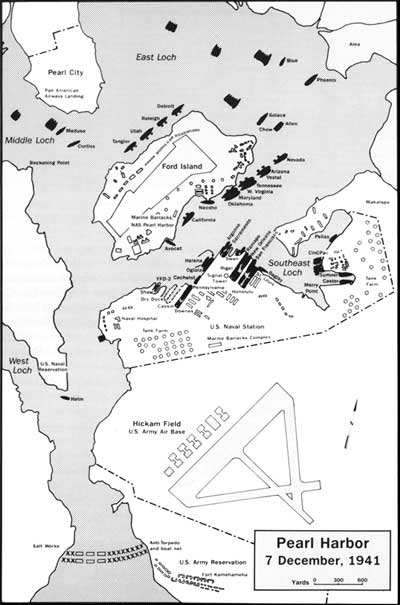

Shapley and Nightingale, meanwhile, reached the mooring quay alongside which Arizona lay when an explosion blew them into the water. Nightingale started swimming for a pipeline 150 feet away but soon found that his ebbing strength would not permit him to reach it. Shapley, seeing the enlisted man's distress, swam over and grasped his shirt front, and told him to hang onto his shoulders. The strain of swimming with Nightingale, however, proved too much for even the athletic Shapley, who began to experience difficulties himself. Seeing his former detachment commander foundering, Nightingale loosened his grip on his shoulders and told him to go the rest of the way alone. Shapley stopped, however, and firmly grabbed him by the shirt; he refused to let go. "I would have drowned," Nightingale later recounted, "but for the Major." Sergeant Baker had seen their travail, but, too far away to help, made it to Ford Island alone. Several bombs, meanwhile, fell close aboard Nevada, moored astern of Arizona, which had begun to hemorrhage fuel from ruptured tanks. Fire spread to the oil that lay thick upon the water, threatening Nevada. As the latter counterflooded to correct the list, her acting commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander Francis, J. Thomas, USNR, decided that his ship had to get underway "to avoid further danger due to proximity of Arizona." After receiving a signal from the yard tower to stand out of the harbor, Nevada singled up her lines at 0820. She began moving from her berth 20 minutes later. Oklahoma, Nevada's sister ship moored inboard of Maryland in berth F-5, meanwhile manned air-defense stations at about 0757, to the sound of gunfire. After a junior officer passed the word over the general announcing system that it was not a drill — providing a suffix of profanity to underscore the fact — all men not having an antiaircraft defense station were ordered to lay below the armored deck. Crews at the 5-inch and 3-inch batteries, meanwhile, opened ready-use lockers. A heavy shock, followed by a loud explosion, came soon thereafter as a torpedo slammed home in the battleship's port side. The "Okie" soon began listing to port. Oil and water cascaded over the decks, making them extremely slippery and silencing the ready-duty machine gun on the forward superstructure. Two more torpedoes struck home. The massive rent in the ship's side rendered the desperate attempts at damage control futile. As Ensign Paul H. Backus hurried from his room to his battle station on the signal bridge, he passed his friend Second Lieutenant Harry H. Gaver, Jr., one of Oklahoma's Marine detachment junior officers, "on his knees, attempting to close a hatch on the port side, alongside the barbette [of Turret I] ... part of the trunk which led from the main deck to the magazines ... There were men trying to come up from below at the time Harry was trying to close the hatch ..." Backus never saw Gaver again.

As the list increased and the oily, wet decks made even standing up a chore, Oklahoma's acting commanding officer ordered her abandoned to save as many lives as possible. Directed to leave over the starboard side, away from the direction of the roll, most of Oklahoma's men managed to get off, to be picked up by boats arriving to rescue survivors. Sergeant Thomas E. Hailey, and Privates First Class Marlin "S" Seale and James H. Curran, Jr., swam to he nearby Maryland. Hailey and Seale turned to the task of rescuing shipmates, Seale remaining on Maryland's blister ledge throughout the attack, puling men from the water. Later, although inexperienced with that type of weapon, Hailey and Curran manned Maryland's antiaircraft guns. West Virginia rescued Privates George B. Bierman and Carl R. McPherson, who not only helped rescue others from the water but also helped to fight that battleships' fires.

Sergeant Woodrow A. Polk, a bomb fragment in his left hip, sprained his right ankle in abandoning ship, while someone clambered into a launch over Sergeant Leo G. Wears and nearly drowned him in the process. Gunnery Sergeant Norman L. Currier stepped from Oklahoma's red hull to a boat, dry-shod. Wears — as Hailey and Curran — soon found a short-handed antiaircraft gun on Maryland's boat deck and helped pass ammunition. Private First Class Arthur J. Bruktenis, whose column in the December 1941 issue of The Leatherneck would be the last to chronicle the peacetime activities of Oklahoma's Marines, dislocated his left shoulder in the abandonment, but survived.

A little over two weeks shy of his 23d birthday, Corporal Willard D. Darling, an Oklahoma Marine who was a native Oklahoman, had meanwhile clambered on board a motor launch. As it headed shoreward, Darling saw 51-year-old Commander Fred M. Rohow (Medical Corps), the capsized battleship's senior medical officer, in a state of shock, struggling in the oily water. Since Rohow seemed to be drowning, Darling unhesitatingly dove in and, along with Shipfitter First Class William S. Thomas, kept him afloat until a second launch picked them up. Strafing Japanese planes and shrapnel from American guns falling around them prompted the abandonment of the launch at a dredge pipeline, so Darling jumped in and directed the doctor to follow him. Again, the Marine rescued Rohow — who proved too exhausted to make it on his own — and towed him to shore. Maryland, meanwhile inboard of Oklahoma, promptly manned her antiaircraft guns at the outset of the attack, her machine guns opening fire immediately. She took two bomb hits, but suffered only minor damage. Her Marine detachment suffered no casualties.

|