| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

OPENING MOVES: Marines Gear Up For War by Henry I. Shaw, Jr. Pacific Theater Throughout 1941, the U.S. and Japan sparred on the diplomatic front, with the thrust of American effort aimed at halting Japanese advances on the Asian mainland. In March, the government of Premier Prince Konoye in Japan sent a new representative to Washington, Ambassador Kichisaburo Nomura, whose task was to negotiate a settlement of differences between the two nations. He was confronted with a statement of the basic American bargaining position that was wholly in compatible with the surging nationalism of the Japanese militarists who were emboldened by their successes in China. The U.S. wanted Japan to agree to respect the territorial integrity and sovereignty of all nations; to support the principle of noninterference in the internal affairs of other countries; to agree to a policy of equal access to all countries, including commercial access; and to accept the status quo in the Pacific.

The chance of Japan accepting any of these stipulations vanished with the German invasion of Russia in June. Freed from the threat of the Russians, the Japanese moved swiftly to occupy southern Indochina and reinforced their armed forces by calling up all reservists and increasing conscriptions. In the face of this new proof of Japanese intent, President Roosevelt froze all Japanese assets in the United States, effectively severing commercial relations between the two countries.

In October, a new militaristic government headed by General Hideki Tojo seized power in Tokyo, and a new special ambassador, Saburo Kurusu, was sent to Washington, ostensibly to revitalize negotiations for a peaceful settlement of differences. Short of a miracle, however, the Japanese Army and Navy leaders did not consider peace a likely outcome of the talks with the Americans. They were, in fact, preparing to go to war. If war came, U.S. Marines would be among the first to experience its violence. In China, Marines had a garrison role in foreign concessions at Shanghai, Peiping, and Tientsin, and in the Philippines, they had sizeable guard units at the naval bases at Cavite and Olongapo on Luzon Island. They provided as well ships' detachments for the woefully few cruisers of the Asiatic Fleet head quartered at Manila. In the Western Pacific's Mariana Islands, there was a small naval station on the Navy governed island of Guam, a certain Japanese wartime target. American Samoa in the southeast Pacific, whose islands were also a Navy responsibility, was strategically vital as guardian of the sea routes to New Zealand and Australia from the States. At Pago Pago on Tutuila, American Samoa's largest island, there was a deep harbor and a lightly manned naval base. Recognizing its isolation and vulnerability to Japanese attack, the Navy began deploying Marines to augment its meager garrison late in 1940. The advance party of Marines who arrived at Pago Pago on 21 December were members of the 7th Defense Battalion, which had been formally activated at San Diego on the 16th. Initially a small composite outfit of 400 men, the 7th had a headquarters battery, an infantry company, and an artillery battery as well as a detail whose task it was to raise and train a battalion of Samoan natives as Marine infantrymen. The Samoans, who were American nationals, would help the 7th defend Tutuila's 52 square miles of mountainous and jungled terrain. The defense battalion's main body reached Pago Pago in March 1942 and the 1st Samoan Battalion, Marine Corps Reserve, came into being in August. The Marines in Samoa, thinly manning naval coast defense and antiaircraft guns at Pago Pago and patrolling Tutuila's many isolated beaches were acutely aware that their relative weakness invited Japanese attack. They shared this heightened sense of danger with the Marines in the western Pacific, in China, on Luzon, and at Guam, as well as other defense battalion Marines who were gradually manning the island outposts guarding Hawaii. These few thousand men all knew that they stood a good chance of proving one again the time-honored Marine Corps recruiting slogan "First to Fight," if war came.

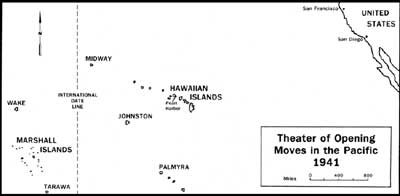

In 1938, the Navy's Hepburn Board had determined that four small American atolls to the south and west of Pearl Harbor should be developed as American naval air bases and defended by naval aircraft and Marine garrisons. The two largest atolls of the four were Wake, 2,000 miles west of Hawaii in the central Pacific near the Japanese Mar shall Islands group, and Midway, 1,150 miles from Oahu, and not far from the international date line. Both islands were way stations for Pan American clipper service to the Orient. Midway also served as a relay station for the trans-Pacific cable. Eight hundred miles southwest of Pearl Harbor lay Johnston Atoll, whose main island could accommodate an airfield and a small garrison. Palmyra, 1,100 miles south of Hawaii, had barely enough room for an airstrip and a bob-tailed defense force. The islands at Wake and Mid way each had room enough to accommodate a battalion of defending Marines as well as airfields to hold several squadrons of patrol and fighter aircraft. The Navy's 14th Naval District, which encompassed the Hawaiian Islands and the outpost atolls, as well as Samoa, was responsible for building defenses and providing garrisons, both ground and air. The Marine contingents were the responsibility of Colonel Harry K. Pickett, Marine Officer of the 14th District and Commanding Officer, Marine Barracks, Pearl Harbor Navy Yard. Preliminary surveys of the atolls and Samoa were conducted by members of Pickett's staff in 1940 and early 1941. Civilian contractors were selected to build the airfields and their supporting installations, but most of the work on the coast defense and antiaircraft gun positions, the bunkers and beach defenses, fell to the lot of the Marines who were to man them. Midway was slated to have a full defense battalion as its garrison, Wake drew about half a battalion at first, and Johnston and Palmyra were allotted reinforced batteries.

|