NPS photo

Clues to the geological processes at work in Natural Bridges are everywhere. Sweeping lines pattern the sandstone. This crossbedding illustrates the advance of ancient sand dunes under the force of wind or water. Potholes dot the slickrock, scooped from the rock by water. Desert varnish streaks down canyon walls. Water seeps through the rock at canyon heads. This landscape may seem static, but the powers of wind, water, and time constantly sculpt new worlds. All you have to do is wait.

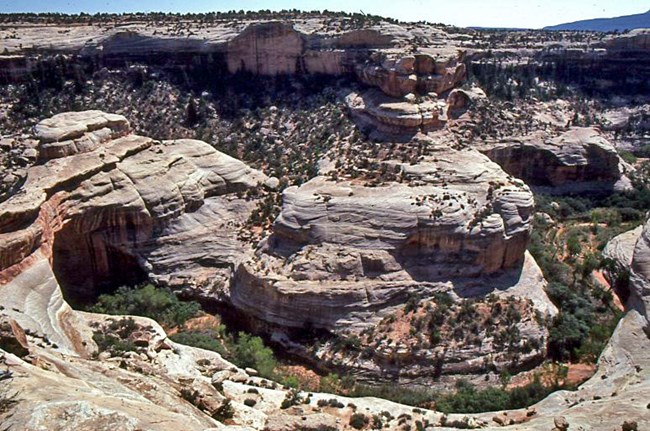

NPS photo Before the Bridges260 million years ago, the area of Natural Bridges was a beach of dazzling white sand, shoreline to the sea covering eastern Utah. Over time, water spread and receded, depositing layers of sand, silt, and mud. Today, visitors can spot these stacked layers, or rock strata, on canyon walls. 10 million years ago, plates colliding below the surface pushed these layers upward. This uplift was incredibly slow, about one hundredth of an inch per year. This area is now a high desert called the Colorado Plateau. After uplift, the Colorado River and its streams cut into the plateau and created winding canyons.

NPS photo A Bridge is bornSome streams wound back and forth in folds like ribbon candy. Thin canyon walls separated the different turns. As water pounded against these walls, eventually the rock crumbled. This left thin natural bridges of rock above the newly-made streambed. At first, each bridge is thick and massive like Kachina Bridge. Erosion works away at the rock, making the bridge more delicate over time, like Owachomo Bridge. Eventually, the bridge collapses. Owachomo is probably the oldest bridge within Natural Bridges National Monument, but how old is old? We don’t know for sure. Geologically speaking, the bridges are relatively recent and short-lived formations. Sandstone erodes at different rates, so the exact age of the bridges is difficult to determine. The Many-Colored LandscapeSoutheastern Utah is a land of radiant color. In the hills, pale greens mingle with gray and white. Mesa tops glow with the red of the setting sun. Much color in canyon country derives from the presence of iron in different combinations with oxygen. Oxygen rusted the iron a brilliant orange-red. Without enough oxygen, iron turns green. When iron combines with both hydrogen and oxygen, it becomes yellow-orange limonite. Beneath the multi-colored mesas, the Cedar Mesa Sandstone appears startlingly white. The ancient sea’s waves washed nearly all of the darker minerals away, leaving only white quartz sands behind.

|

Last updated: April 18, 2025