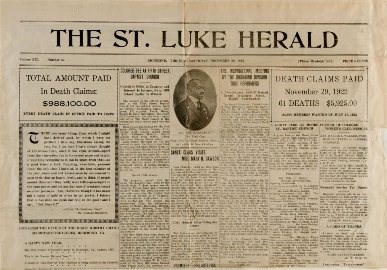

Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site “What we need is an organ, a newspaper to herald and proclaim the work of the Order. No business, no enterprise, which has to deal with the public, can be pushed successfully without a newspaper…” -Maggie Lena Walker From its inception, The St. Luke Herald formed a crucial part of the Independent Order of St. Luke's internal communications. In her 1901 proposal, Mrs. Walker described The Herald as “a trumpet to sound the orders, so that the St. Luke upon the mountain top, and the St. Luke dwelling by the side of the sea, can hear the same order, keep step to the same music, march in unison to the same command, although miles and miles intervene." Connecting individual members and coordinating across councils became increasingly important as the Independent Order of St. Luke recruitment teams fanned out across the nation and the organization’s membership grew. She also identified the paper as essential to the success of the Order's insurance arm and ventures such as the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank and the St. Luke Emporium.

December 30, 1922 Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site Editorial The primary editorial focus of the Herald was news coverage of the St. Luke Order, reports of meetings and conferences, the economic health of the organization, the economic stability of the Order's insurance arm, the amount of death benefits paid out, obituaries of members, the activities of the Order's Juvenile Division and public appearances of Mrs. Walker as the Order's Grand Secretary Treasurer. Editorials and news stories would also include social and human interest articles of interest to the community and self-improvement articles to assist and encourage the St. Luke membership. Although the Herald's primary purpose was to provide communications for the St. Luke's membership and promotion of St. Luke economic ventures, its scope was not limited to fraternal news alone. The paper at its very beginning had little choice but to publish stories that reported civil rights abuse of the African American community. In 1902, the same year that the Herald was first published, the Virginia Constitutional Convention rewrote the State Constitution to politically disfranchise African Americans by means of literacy tests and poll taxes with the ultimate goal of the elimination the black vote. In this era of legal oppression of African American rights the Herald's first editorial outspokenly described the paper's mission and pledged to fight injustice, mob rule, Jim Crow Laws, divestment of black public schools and the literacy test. The Herald's staff chose to resist the growing tide of injustice, both in print and by action. It was St. Luke attorney and Herald editorial writer James Hayes who, with his colleagues, engaged in the long, but unfortunately unsuccessful, legal battle against the 1902 state constitution. Two years later, in 1904, The St. Luke Herald once again stepped forward to oppose racial injustice with its editorial campaign against the segregation of Richmond's trolley car system. In January of that year the Commonwealth of Virginia passed a law that granted local transport companies the option of enforcing segregation at the discretion of individual trolley conductors. The Herald and the Richmond Planet both called upon Richmond's African American population to boycott the streetcars by walking instead of submitting to this imposed racism. Later in 1906, the Virginia General Assembly altered the law to require segregation on all means of public transportation. The street car boycott ended, but this peaceful community resistance that lasted for more than a year did inflict serious financial damage to Richmond's trolley company, forced it into receivership, and proved that coordinated economic resistance could become a viable, effective tactic (as it would surely become in the 1950s and 60s).

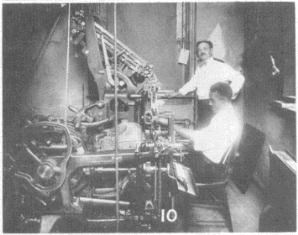

Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site GrowthAs the Independent Order of St. Luke organization grew in the first decades of the twentieth century to include members in twenty-three states and the District of Columbia, the number of subscribers of The St. Luke Herald grew as well. By 1916, the Herald had four thousand subscribers; in 1924 this number had grown to six thousand. This successful expansion in membership however caused issues within the Order's Insurance Department and the overall management system of the organization. In 1928 an accounting firm was hired to review the business processes of all of the St. Luke ventures, Insurance, Banking, Adult Membership, Juvenile Division, the Printing Department and the Herald, to improve the effectiveness of all operations. By February 1929 almost all of this review's efficiencies had been adopted by the Order's trustees except for the recommendation to eliminate the Printing Department to reduce operating costs and payroll. This outsourcing would have meant the elimination of professional African American jobs within the organization, a move that would have been a retreat from the Order's progressive policy to expanded employment opportunities for African Americans. Owning and operating the Printing Department was a point of pride for the Order and its ability to print the twelve page Herald, produce regalia and all other St Luke's print requirements was trumpeted in the Order's advertising. The Printing Department was retained as the elimination of this capability would have been a blow to the Order's belief in its own self-sufficient stance. By 1929 the Herald had eclipsed the Richmond Planet in local circulation to become the city's leading African American weekly. Thirty percent of African American families in Richmond subscribed to The St. Luke Herald, fourteen percent still subscribed to the Planet, and twenty-five percent took an out-of-town weekly such as the Chicago Defender, the Pittsburgh Courier, or the Norfolk Journal and Guide. DeclineUnfortunately the Great Depression would end the economic growth and prosperity of the 1920s in the United States. The impact of the Depression hit the Independent Order of St. Luke at the end of 1931. Membership declined, member dues were late or unpaid, and the profits of the St. Luke ventures fell as the economy slowed. Because of the overall decline in revenue it became necessary for the Order to cut operating costs. Cuts specific to the newspaper included a decline in its scope and size. The Herald shrank from a weekly, twelve-page, newspaper-size paper, with national news and special features, including a children's page, to become a monthly, twelve-page, letter-sized St. Luke Fraternal Bulletin. Additional sacrifices were made when the senior St. Luke's employees, including those on the paper's staff and the printers of the Print Department, took 10 to 70 percent cuts to their own pay to shield the jobs of the newer employees. The Independent Order of St. Luke survived the Depression and carried on through the Second World War into the 1980s, but the St. Luke Fraternal Bulletin never regained the journalistic stature the Herald achieved in its early years. In the 1930s and 40s fewer black newspapers were published nationwide, but those that were had greater circulation than their predecessors. By 1930 the Chicago Defender had a circulation of 280,000 and by World War II the Norfolk Journal and Guide's circulation had grown to 100,000. The Norfolk Journal and Guide was also the only African American weekly from the southern United States to publish a national edition and was the largest employer of African Americans in the South. Once The St. Luke Herald and the Richmond Planet passed from the scene these African American weeklies took up the torch to oppose racial injustice and struggled for economic advancement for African Americans. |

Last updated: January 4, 2017