|

Who is an artist or entertainer that you believe will stand the test of time? That will still be spoken of in 100 or 200 years? Although the entertainment landscape was in many ways different from our own, there were certainly still many entertainers, musicians, and actors who captured the admiration of fans in Martin Van Buren’s time. There are certainly a few artists that modern society still remembers, some that even predate Van Buren’s lifetime, such as Mozart. However, the vast majority of the entertainers of the past are forgotten. After all, 160 years is a long time. But if you had asked Van Buren about the entertainers of his lifetime and who might stand the test of time, he likely would not have given the correct answer.

1830 lithograph by Joseph Kriehuber. Digitalized by Peter Geymayer. Fanny ElsslerWhat were some of Van Buren’s favorite forms of entertainment?Ballet, while popular in Europe, never became quite as widespread in the United States. Despite this, one of the most famous entertainers to cause a stir stateside during Van Buren’s presidency was Fanny Elssler, a ballerina from Austria. Elssler arrived in New York City in 1840 to begin an American tour at the tail end of a many-weeks-long publicity campaign by her agent heralding her arrival. After her first few performances, her celebrity was truly established. People came from far and wide to see her perform, and there was such a demand for seating that seats were often auctioned off to the highest bidder. On several occasions, upon her arrival in a city, she was met by crowds that unhitched the horses from her carriage and dragged it through the streets themselves. She met or performed for numerous famous Americans. Most famously, when she performed in Washington, D.C., Congress could not muster a quorum to vote because too many congressmen were out watching her dance. John Van Buren toured her around New York City, and she met Martin Van Buren at the White House. The tour brought her great financial success as well as fame. By the end of the tour she was successfully charging $1,000 a night for performances as well as keeping gifts she received

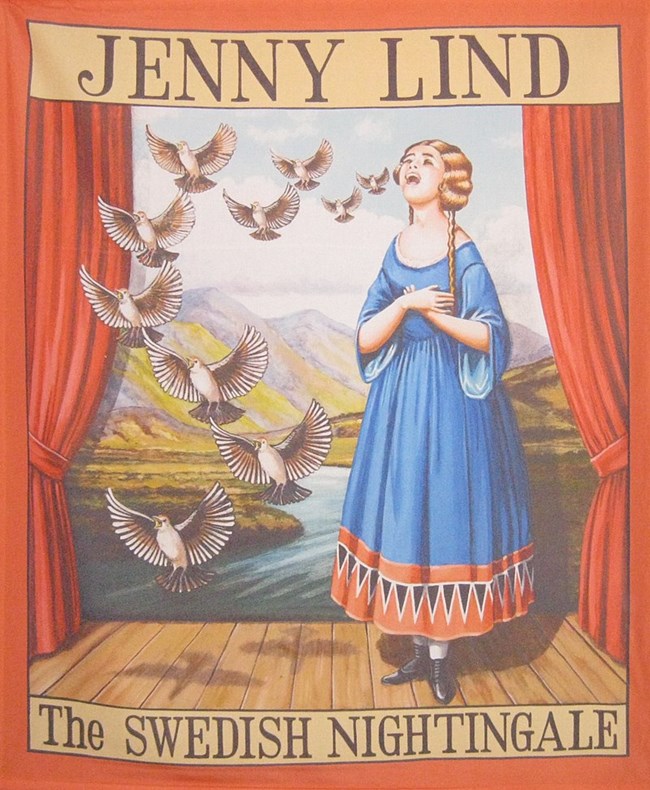

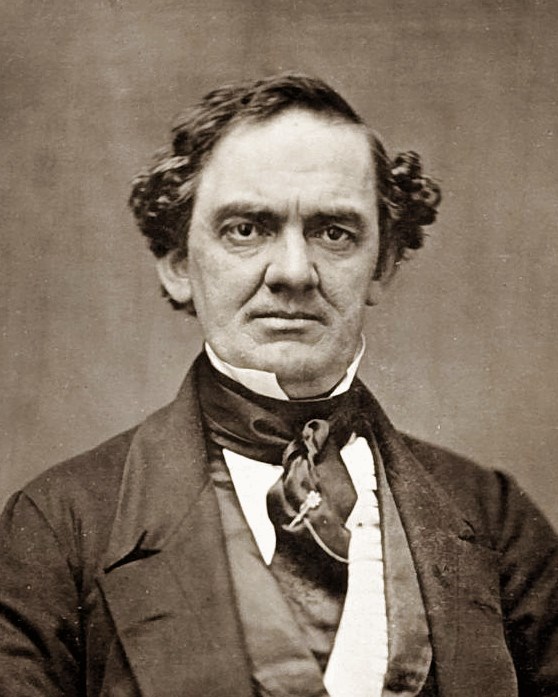

Jenny LindOpera was similar to ballet - a mostly European form of entertainment that enjoyed some popularity among America’s upper-class. But the arrival of another European performer, Jenny Lind, would bring it to the forefront of American Society.Lind had retired at the age of 29 after a whirlwind career of fame throughout Europe, but was convinced to come out of retirement by future American circus magnate P. T. Barnum. Lind saw this as an opportunity to make money for her favorite charities, mainly the Swedish public-school system, and accepted. Barnum aggressively promoted her arrival, referring to her as the “Swedish Nightingale” and stating that her music would be good for American moral education. The tour was wildly successful, but Lind eventually became uncomfortable with Barnum’s marketing of her. His media frenzy surrounding her created such demand for her performances that Barnum often sold the tickets via auction. Lind decided to finish the tour on her own, which the earlier contract she had negotiated with Barnum stipulated she could do. Newspapers reported the fame and adulation that followed her as “Lindmania,” and she eventually returned to Sweden having made the equivalent of around ten million dollars for her 90 performances. Barnum for his part made the equivalent of around 15 million.

By unattributed (Harvard Library) P. T. BarnumVan Buren is known to have enjoyed opera and other European forms of entertainment in the latter years of his life. Yet he also retained a love for entertainment that he himself deemed as a form of escapism, reading for pleasure being his biggest example. The two previous people's careers highlight more escapist forms of entertainment.P. T. Barnum remains much more of a household name in the modern United States than either of the previously mentioned entertainers. This is perhaps due in large part to the survival of the circus he created in the intervening centuries. But why did the circus survive? Cirques were much more affordable for the average American. Barnum, however, did not start his career with his now famous circus. His first foray into entertainment was in creating a traveling theater troupe in the mid-1830s. The acts associated with his early performances were often deeply exploitative. The story of his first "act" was a good example. In 1835, Barnum purchased a blind and almost completely paralyzed enslaved woman named Joice Heth, whom a business associate of his was exhibiting in Philadelphia. The act claimed she was 160 years old and George Washington’s former nurse. She died a year later, and as a final "performance," Barnum hosted a live autopsy of her body. Spectators could pay 50 cents to watch as Barnum sought to "prove" that she was in fact only 80 years old at the time of her death. Barnum’s financial success with his troupe ended during Van Buren’s presidency when the financial Panic of 1837 disastrously impacted both of their careers. Barnum was able to diversify, and actually became a Republican politician before and during the Civil War. After the Civil War, Barnum returned to the traveling circus business. His work largely defined circuses as we still think of them today.

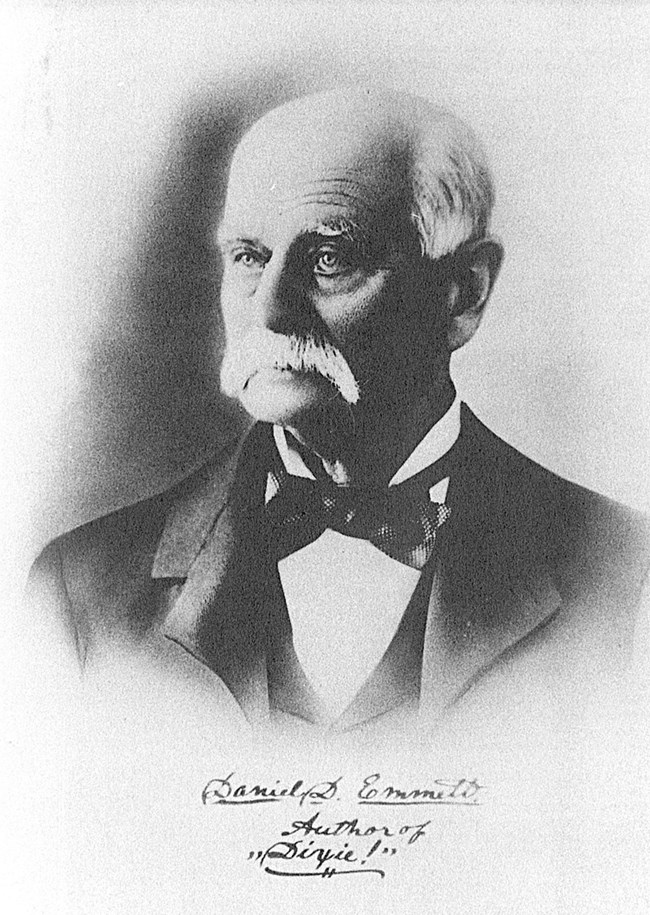

Photograph of Dan Emmett taken from the belongings of Ben and Lew Snowden. Dan EmmettIt would be remiss to conclude any discussion of 19th century entertainment without discussing Dan Emmett, a man who is largely credited with solidifying the creation of an American form of entertainment.Emmett was a founding member of the Virginia Minstrels, and while they were far from the first to put on "minstrel shows," they are largely responsible for codifying what would become a national art form. The Virginia Minstrels consisted of four members who performed music and comedy in blackface. Before Emmet’s group began their performance in New York City, minstrelsy applied to any number of white traveling performers. But after it was synonymous with blackface, Minstrel performances in this fashion became enormously popular from their beginnings in the 1840's and lasted well into the 20th century. At first, there was great diversity in the content of the performances. One example is the now popular children’s song "Jimmy Crack Corn," originally credited to Dan Emmett’s Virginia Minstrels. The song features an enslaved man describing, with undertones of celebration, the death of his master. By a decade later, these performances had crystalized into romanticized and strictly pro-slavery narratives. Their dialogue was generally racist, satiric, and white in origin. Caricatures such as the prominent character "Jim Crow" were depicted as lazy, unwilling to work, and, in some cases, craving some form of subjugation. There were numerous examples of songs about slaves yearning to return to their masters, and figures like northern dandies, African American freedmen, made frequent appearances. Their obvious point, explicitly or otherwise, was that slavery was a benign institution, and northerners should not be concerned with the lives of the enslaved.The minstrel shows well outlasted Van Buren’s lifetime, but their legacy lasted even longer. Many of the stereotypes projected onto African Americans still exist, and even find themselves in the media. Both the popular film Gone With The Wind and Disney’s infamous Song of the South in many ways perpetuate the caricatures that minstrel show performances often presented. The most widely referenced minstrel show character name is probably the character associated with the popular song lampooning a black man, "Jump Jim Crow." In the 20th century, Jim Crow became the name associated with segregationist laws throughout the United States in the 20th century. These four entertainers, or entertainment groups, provide us with a broad view of America’s entertainment landscape during Van Buren’s lifetime. Despite Elsseler and Lind’s popularity and wild success in their own lifetimes, they aren’t really remembered by modern Americans. P.T. Barnum has the widest name recognition of the four discussed here, perhaps because the idea of circuses are so closely tied to his name. The Virginia Minstrels, though, are perhaps in the most interesting position of the four. The name Virginia Minstrels, or its founder, Dan Emmett, is not well known in modern America. And yet, culturally, the tropes, stereotypes, and, in some cases, songs popularized by their performances permeate our everyday life. In the end, entertainment may have been what they sought to make, but in a larger sense, they made real history as well. Of the four, it seems likely that Van Buren would have chosen Lind or Elssler as the most likely to stand the test of time, and yet it is fascinating to think that it might well be the tropes of Minstrel shows that would be the most intelligible to Van Buren in modern media. A modern showing of Gone with the Wind would be something he could understand culturally. What modern artist, entertainer, or creator do you think will stand the test of time? |

Last updated: April 23, 2025