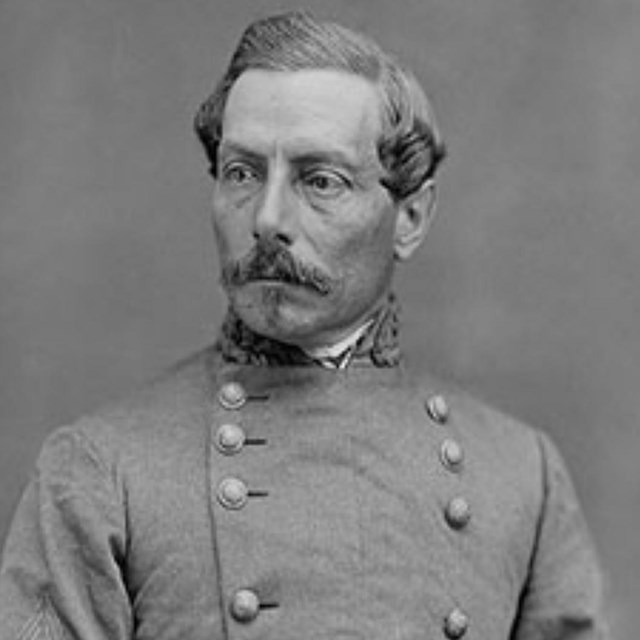

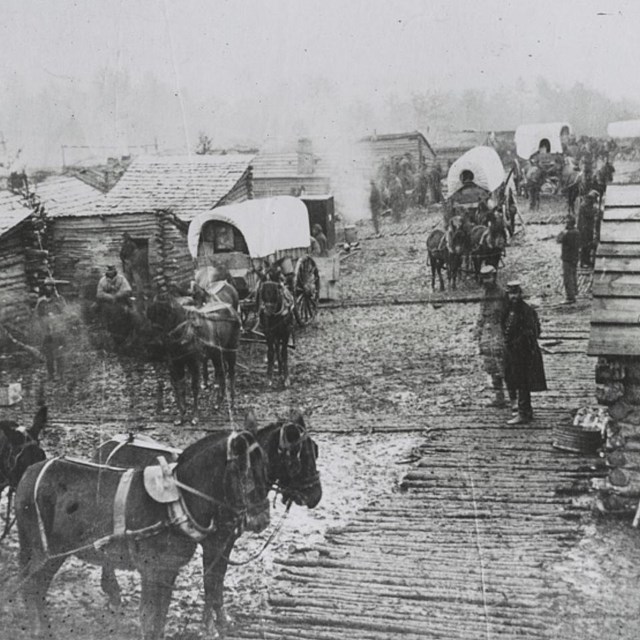

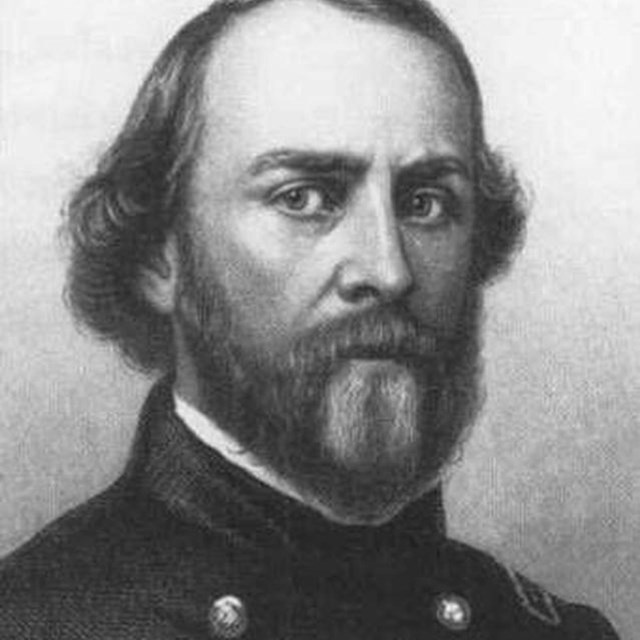

Prelude to BattleCheers rang out in the streets of Washington on July 16, 1861 as Gen. Irvin McDowell’s Federal army, 35,000 strong, marched out to begin the long-awaited campaign to capture Richmond and end the war. It was an army of green recruits, few of whom had the faintest idea of the magnitude of the task facing them. McDowell’s lumbering columns were headed for the vital railroad junction at Manassas. Here the Orange and Alexandria Railroad met the Manassas Gap Railroad, which led west to the Shenandoah Valley. If McDowell could seize this junction, he would stand astride the best overland approach to the Confederate capital. On July 18, McDowell’s army reached Centreville. Five miles ahead a small meandering stream named Bull Run crossed the route of the Union advance. Guarding the fords from Union Mills to the Stone Bridge were 22,000 Southern troops under the command of Gen. Pierre G.T. Beauregard. McDowell first attempted to move toward the Confederate right flank, but his troops were checked at Blackburn’s Ford. He then spent the next two days scouting the Southern left flank. In the meantime, Confederate Gen. Joseph E. Johnston's army, stationed in the Shenandoah Valley with 10,000 Confederate troops, were ordered to support Beauregard. Johnston gave an opposing Union army the slip and, employing the Manassas Gap Railroad, started his brigades toward Manassas Junction, with most arriving July 20 and 21.

July 21, 1861Morning The head of Union General Irvin McDowell's flanking column begins its march. The order of march consists of:

1. Daniel Tyler's Division: Tasked with diversionary attacks against the Confederate position at the Stone Bridge. 2. David Hunter's Division: Leading division in the flanking column - to cross at Sudley Springs Ford 3. Samuel Heinztleman's Division: The march is plagued by problems from the beginning, as the leading division slowly makes its way toward the Stone Bridge. As the Federal infantry began to snake its way around the Confederate defenses along Bull Run, the lone report of a cannon was heard.

Union artillerist Peter Conover Hains ordered his 30 lb. Parrott Rifle to fire on the Confederates near the Stone Bridge. The shell flew over the Confederate infantry and into the Van Pelt House on the bluff above the creek. The Battle had begun. Around 9 AM, Confederate signal officer E.P. Alexander, from his station on the Wilcoxen Farm, noticed the glint of cannon barrels and bayonets moving well beyond the Confederate army's left flank.

Using the new technologgy of signal flags, Alexander sent a message by wig-wag to Colonel Nathan Evans, the commander of the brigade holding the Stone Bridge: "Look out for your left, you are turned!" Receiving this order, Evans moved a majority of his brigade using farm lanes to cut off the Union attack. At roughly 10AM, the head of the Union attack column reached the vicinity of Matthews Hill. At the front was a brigade of New Englanders commaned by Colonel Ambrose E. Burnside.

For nearly two hours, Union and Confederate soldiers from eight different states were engaged across the Matthews Farm. Regiments involved hailed from New York, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, South Carolina, Louisiana, Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi. As one participant in the engagement noted, "I was in the very presence of death." As additional federal troops entered the fight, the Confederate line began to crack and quickly retreated southward, through the yard of the Stone House, and up the slopes of Henry Hill. While there was no large-scale assault made by the Federal army following their success on Matthews Hill, sporadic fighting across the battlefield continued.

With Confederate soldiers retreating up the northern slopes of Henry Hill, various newly arrived New York regiments continued the chase and engaged with their retreating foe around the Stone House. During this clash, Colonel Henry Slocum of the 27th New York Infantry was wounded. Further to the east, elements of various Confederate commands, including Colonel Wade Hampton's Hampton Legion and General Thomas Jackson's Virginia Brigade, engaged General Erasmus Keyes' New Englanders around the buildings of the James Robinson farmstead. While successful in pushing the Confederates back, Keyes called off his assault and remained in a position near the Stone Bridge for the remainder of the day. AfternoonThe Confederate refugees of the fighting on Matthews Hill were met by Generals Joseph Johnston and PGT Beauregard who immediately began the task of restoring order and creating a defensable position. Coming into position on the eastern slope of the hill were the 2,500 Virginians under General Thomas J. Jackson and a line of 13 artillery pieces. This new line was quickly challenged by federal soldiers striking at their right near the Robinson Farm and a long range artillery bombardment that continued for over an hour. At some point during the afternoon fighting on Henry Hill, Confederate General Barnard Bee remarked to the men of the 4th Alabama Infantry: "Yonder stands Jackson like a 'Stonewall.' Let us go to his assistance." With those words, the legend of Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson and the "Stonewall" Brigade were born. Gen. Irvin McDowell ordered the artillery batteries of Captains James Ricketts and Charles Griffin from their positions on Dogan Ridge to the western slopes of Henry Hill. Despite their protestations of this unsupported movement and their desires to remain at a safe distance to maintain their fire, Griffin and Ricketts' eleven (11) guns moved forward.

As Ricketts' guns moved into position on the hill, he quickly came under fire from Jackson's infantry and the massed Confederate artillery opposite him. In this early action on Henry Hill, Ricketts' cannoneers also opened fire toward the Henry House, with the artillery captain noting that his men "completely riddled it." Unbenknowst to Ricketts at the time, these salvos mortally wounded Judith Carter Henry, who soon succumbed to her wounds. Following the battle, soldiers buried her in her garden. The Federal artillery was not alone on Henry Hill for long. The promised infantry support soon arrived on the hill in the form of New Yorkers, Minnesotans, and the United States Marine Corps Battalion. This infantry surged across the hill and engaged with Jackson's brigade at close range.

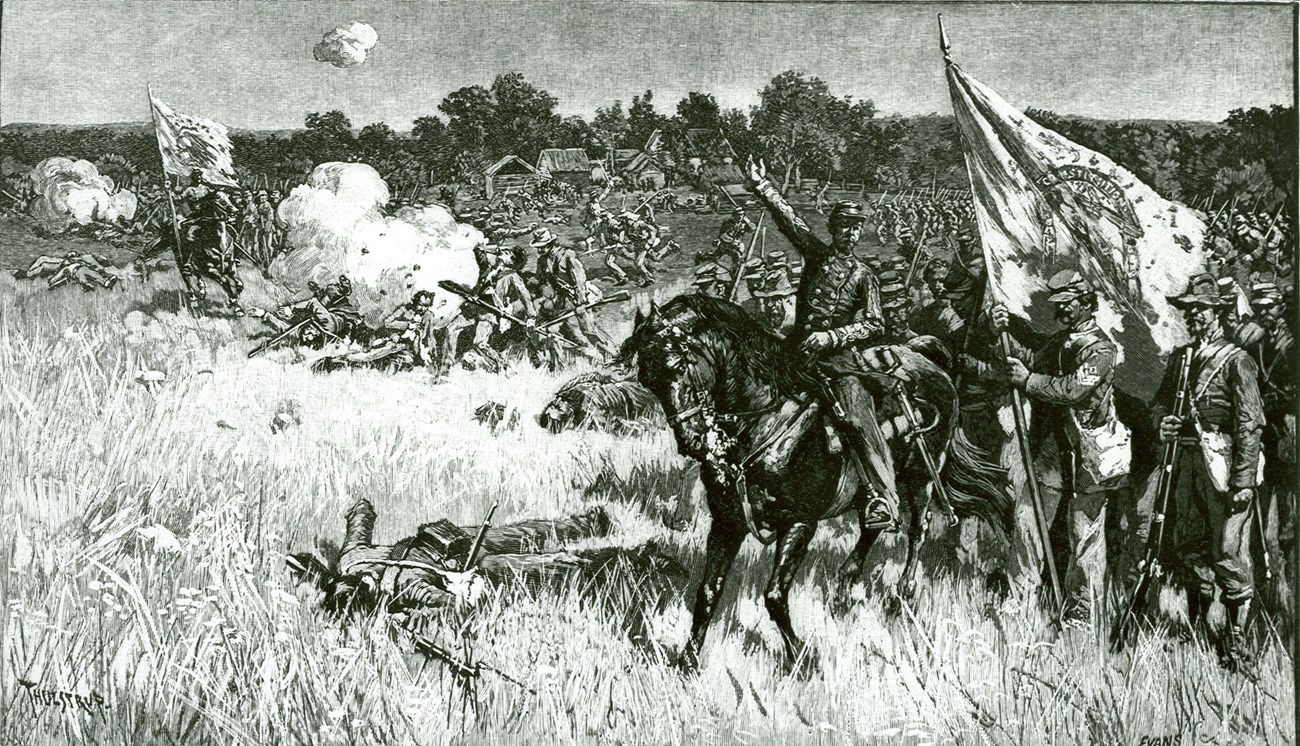

At nearly the same time, Captain Charles Griffin moved two of his five artillery pieces from their position north of the Henry House to the southern edge of the hill in an effort to enfilade the Confederate line. Confusion soon reigned as Griffin noticed an unknown body of troops moving around his guns. Believing them to be Confederates, the artillery opened fire. Soon, the federal army's artillery arrived and countermanded this order, believing these troops to be Griffin's supports. The unidentified body of men soon revealed themselves to be Confederates and promptly charged the guns and captured them. While these guns would change hands a couple of times, this marked a turning point in the fight on Henry Hill and in the battle more broadly. Following the capture of Griffin's two advanced guns, Jackson ordered his men to advance. Admonishing his men to "yell like furies," elements of his brigade surged towards the artillery on the western slope of Henry Hill. The fighting around James Ricketts' six cannons grew with intensity as the position changed hands three times. One Virginian noted of this fighting that: "The shouts of the combatants, the groans of the wounded and dying and the explosion of shells made a complete pandemonium…the atmosphere was black with the smoke of the battle."

During the fighting on Henry Hill, Gen. McDowell ordered 13 individual regiments to attack the hill. A soldier in a Wisconsin regiment noted of the position in the Sudley Road, "The poor fellows had crowded in and crawled one upon another, filling the ditch in some places three or four deep…I will not sicken you with a description of the road." Soon the fighting shifted to the west, as additional federal and confederate brigades engaged on Chinn Ridge. Colonel Oliver Howard's New Englanders were forced to retreat soon after arriving on this exposed position. The retreat soon grew as the whole Federal army began to withdraw from the field. AftermathAt first the withdrawal was orderly. Screened by the regulars, the three-month volunteers retired across Bull Run, where they found the road to Washington jammed with the carriages of congressmen and others who had driven out to Centreville to watch the fight. Panic now seized many of the soldiers and the retreat became a rout. The Confederates, though bolstered by the arrival of President Jefferson Davis on the field just as the battle was ending, were too disorganized to follow up on their success. Daybreak on July 22 found the defeated Union army back behind the bristling defenses of Washington.Learn More About First Manassas

|

Last updated: July 15, 2024