IntroductionAs cotton textile mills took over the landscape of Lowell, the laborers that worked in the mills needed housing that was near enough to commute on foot each day. The corporations built boarding houses and hired keepers to solve this problem and enable another level of control over the workers lives. The exhibit is housed in the Patrick J. Mogan Cultural Center, 40 French Street, in a reconstructed corporation boarding house. To learn more about this exhibit and to find current hours of operation, visit our Mogan Cultural Center page.

Lowell Historical Society The Boarding HousesIncorporated as a town in 1826, Lowell grew to contain numerous water-powered factories, as well as boarding houses for its workers. To attract and meet the basic needs of a varied workforce, the textile corporations built low-cost, communal living units. Early boarding houses in Lowell and other New England mill towns were two -and- a- half- story, whitewashed duplexes made of wood. By the mid-1830s, three-and-a-half-story brick rowhouses, reflecting the now more familiar Lowell boarding house design, became the norm. These dwellings housed 20 to 40 people and contained a kitchen, a dining room and parlor, a keeper’s quarters, and up to ten bedrooms. Row after row of boarding house blocks visually distinguished Lowell from earlier New England mill towns. The majority of the residents in Lowell’s boarding houses were single, female wage earners employed in the city’s textile mills. Known as “mill girls,” these young women hailed largely from New England’s rural villages and farms. They lived in closely supervised corporation-controlled boarding houses. The textile corporation managers sought control over their workers not only inside the mills, but also within the community. Their paternalistic practices extended to the moral guardianship and physical care of the young factory women.

Boarding House LifeUnder this early form of corporate paternalism, the millworkers’ behavior came under the watchful eyes of the boarding house keepers. The corporations required the keepers to report any unacceptable conduct to mill managers. Intemperance, rowdiness, illicit relations with men, and “habitual absence from worship on the Sabbath” were grounds for dismissal from the factory and removal from the boarding house. The keepers were also responsible for purchasing or renting everything needed to furnish a house and feed its occupants. Room and board costs, which ranged from $1.25 to $1.50 per week during the 1830s and 1840s, were deducted from wages. For this amount, workers received three meals a day, limited laundry service, and a bed in a shared room. Most mill workers shared living space with relatives, friends from home villages, and strangers. Their bedrooms provided little privacy. Typically four to six people slept in a room and often two women shared a double bed. Despite the overcrowded conditions, communal living in the boarding houses fostered close bonds between working women and helped new hires adjust to factory toil and city life. Although boarding house keepers were employed by the corporations, they functioned as small businessmen and women. TransitionsThe boarding houses remained an important part of the Lowell factory system through the late 19th and early 20th century. During these decades, Lowell’s textile corporations expanded their mills and improved their housing, adding such features as indoor plumbing, central heating, and other amenities. The mill workers who lived in the boarding houses, however, were increasingly foreign-born men and women. While the first workers in Lowell were of English, Scottish, and Irish descent, later workers included French-Canadian, Greek, and Portuguese immigrants, as well as immigrants from Poland and other Eastern European countries. They took up the many unskilled jobs in the mills. Immigrant workers, often in family groups, predominated as boarding house residents. By 1900, male boarding house residents outnumbered female, a remarkable departure from Lowell’s first few decades of industrial development.

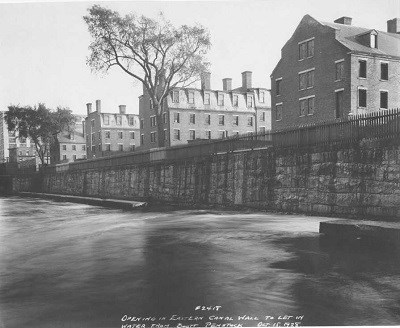

End of an EraChanging social values and competitive capitalism rendered old forms of paternalism obsolete. When corporations found boarding house maintenance too expensive, they began selling off the buildings, converting them to storage facilities or demolishing them to make way for warehouses or other structures. The Boott Mills’ corporation housing continued to be home to mill workers and their families long after the Yankee “mill girls” ceased to be the major part of the labor force. The boarding house system continued well into the 20th century, becoming mainly privately-run, family tenement housing, before finally expiring along with Lowell’s textile industry. Neglect and urban renewal resulted in the loss of almost all of Lowell’s boarding houses. Boott Cotton Mills' Boarding HousesThe Boott Cotton Mills, incorporated in 1835, originally built eight rows of boarding houses directly across from its factory. Each row of dwellings contained four boarding house units in the center and a tenement unit on each end. Unmarried textile operatives lived in the boarding house units, while supervisors and skilled workers lived with their families in the tenement sections. Unlike the boarding house units, which resembled dormitories, the tenements were more like apartments with individual kitchen facilities. Of brick construction, the boarding house rows measured 150 feet long, 36 feet wide, and were built in the early Georgian style. Their uniform appearance, which was visually enhanced by the lines of tall chimneys, gable-roof dormers, and symmetrically placed windows, expressed the Boott corporation’s desire for orderliness and rigid discipline.

|

Last updated: October 11, 2023