Public Domain New Territory: The Strike of 1834In February of 1834, the agents of Lowell’s mills were beset by hard times. The prices of textiles were falling, the market was sluggish, and much of the cloth being produced in the factories was sitting in warehouses and not selling well enough. In response, a 12.5% wage reduction for workers across the city was proposed and implemented. The mill workers were still not satisfied with a sudden 12.5% cut in their wages, however. Women met in the mills after work to plan a course of action, sending petitions around the city and talking about how best to get those wages back. Many of these methods would be used later by suffragists nationwide as well. Before a plan could be fully developed, the leader Julia Wilson was fired in the hopes this would crush the resistance. Wilson instead gave the signal to begin walking out early. Eight hundred women across the city left work to protest the wage cut and the Wilson’s unfair termination. All in all around a sixth of the working population left the mills, paraded around the city, and visited other mills in the hopes of drawing those workers out to aid in the fight. Ultimately, the strikers did not get what they asked for in 1834 and either left Lowell or returned to work. The turn-out was rushed and not fully organized, brought on by the leader’s abrupt termination. Mill owners were also incredibly efficient in handling the strike. However, the mill girls learned a lot from their first attempt at striking and would go on to have more success in the future, learning from past mistakes. The wage cuts themselves were the main reason many women turned out in February of 1834, but these workers also felt attacked on a more personal level. Women were indignant as “daughters of freemen” mirroring language popular in the American Revolution. The proposed wage cuts would threaten the women’s economic independence, which was something they took pride in, as it was often difficult for a single woman to make her own money. When a woman married, all of her funds legally became her husband’s through a system called “coverture” – which also prevented a woman from voting. The mill owners thought the protesters were being ungrateful and should take whatever they were given. The language they used and their opinion of the female strikers in particular focused on how “unseemly” or “unwomanly” their actions were. The chief agent of the Lawrence Mills in Lowell, William Austin, on multiple occasions referred to the protesters as “amazons,” which in Greek mythology are a race of incredibly strong and violent women. It was not intended as a compliment.

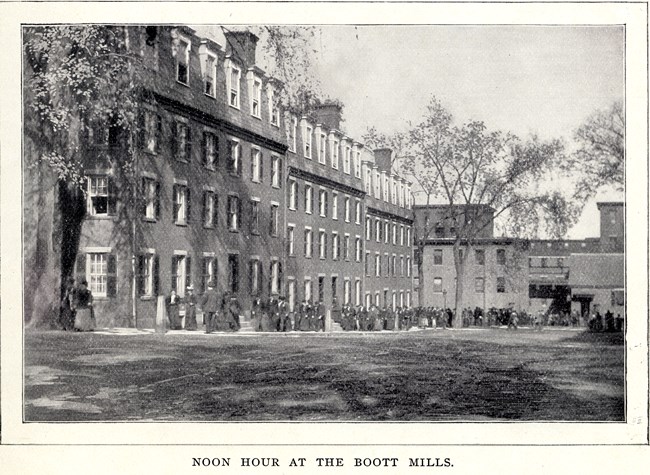

Lowell NHP Collection Take Two: The Strike of 1836In October of 1836, in the face of rising inflation, boardinghouse keepers – the women in charge of cleaning, cooking, and caring for the workers living on factory grounds – made the argument to management that they could no longer make ends meet. In response, mill management increased the amount of money deducted from women’s weekly earnings for room and board. Without a corresponding increase in pay this was essentially a pay cut, and that is certainly how the workers saw it. Unlike the 1834 pay cut, the market was booming at this time and in fact the factories were looking for more workers to keep up with demand, making a strike incredibly costly. The women knew this, and used it to leverage support for the cause. This time anywhere from 1500-2000 workers turned out, and with better planning they were able to keep up the strike for months at a time instead of just a few days like two years prior. The Factory Girls’ Association was established to help workers cover the cost of boarding while they were not earning wages, and the mills were forced to work below capacity for much longer. Many women would learn to organize and rally support during strikes like these, and go on to use that knowledge to support other causes like antislavery or women’s rights. One prominent striker in 1836 was Harriet Hanson (1825-1911). Though only 11 years old at the time, the young worker found herself deeply moved by the workers’ display. This experience would inform Hanson’s later opinions of woman suffrage and labor. Ultimately, many of the companies would cave at least to some degree. At the Hamilton Company, rate increases were removed for those paid on a daily basis. They were removed entirely at the Boott and Merrimack Corporations. |

Last updated: October 26, 2021