NPS / James P. Jones Photography RI

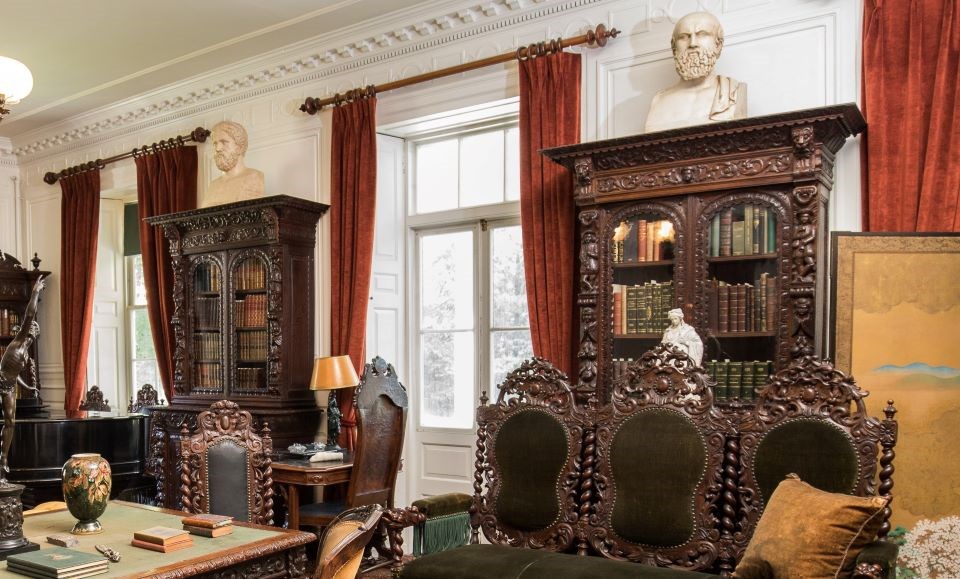

The historic books represent the largest single group of objects at Longfellow House - Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site. They number approximately 11,000 volumes dating from the fifteenth to twentieth century, and consist of the combined libraries of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Fanny Appleton Longfellow, their five children, grandson Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Dana, and extended family members. Over 5,000 volumes are marked with Henry Longfellow’s own signature, his bookplate, or a presentation inscription to the poet. The collection illustrates Longfellow's international academic, literary, and personal interests.

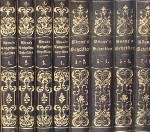

LanguageThe bulk of the collection is in English, but 45 languages, including dialects, are represented in the historic library. Many of these reflect Henry Longfellow’s interest in language and linguistics, with the majority in French, German, Italian, and Spanish – the languages he taught as a professor of Modern Languages at Harvard College. As a student and teacher of language, Longfellow collected utilitarian dictionaries and manuals; references he acquired on his first trip to Europe in 1826-29 include Theoretical and Practical Grammar of the French tongue, Grammaire Allemande, and Schul-und Reisetaschen Worterbuch der Franzoisischen und Deutschen Sprache. Even more interesting to Longfellow was European literature in its original language: Voltaire, Hugo, and Rousseau in French; Goethe and Richter in German; Dante and Goldoni in Italian; and Cervantes and Calderon de la Barca in Spanish. A smaller but still significant group of 174 Scandinavian-language books – today mostly housed in a tall study window retrofitted with bookshelves – indicate his interest in the languages and literature of Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Iceland. Even those languages represented by only one or two volumes – Bengali, Hindi, Sanskrit, Chinese, Greenlandic, Hungarian, Hebrew, Occitan, Persian, Romansh, Cornish, Creole, Frisian, Celtic, and Welsh – demonstrate the range of the travel and linguistic interests of the family.

Presentation CopiesNumerous presentation copies from admiring authors and friends illuminate Longfellow’s status as the preeminent American poet. The collection in the house today includes 484 volumes sent compliments of their authors, editors, publishers, and translators. Documents in the archive indicate that over 800 additional presentation copies were donated to Harvard following Henry Longfellow’s death by his daughter Alice and the Longfellow House Trust.

Museum Collection (LONG 2650) Collecting

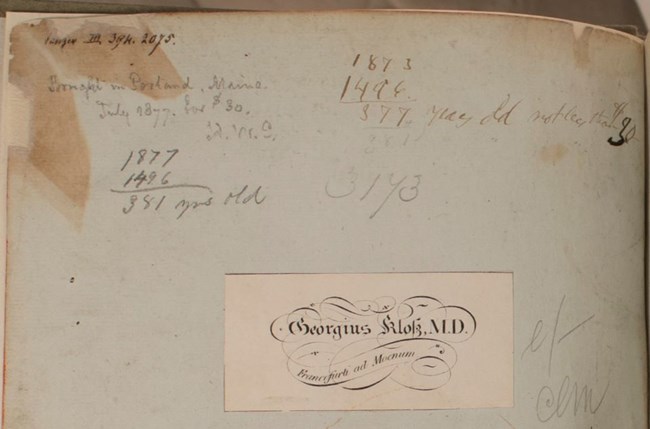

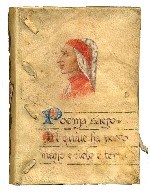

Though many of the books in the Longfellows’ library are beautifully bound, luxury objects, the majority of them were purchased for use and actively read. A few exceptions are books collected “on account of [their] age,” including Plutarch’s Lives, illustrated atlases of China, Africa, and Asia from the 1670s, and folios printed by Giambattista Bodoni from the 1790s. Reading Interests

The Longfellows immersed themselves in reading and literature for both work and leisure, and entries in family journals and letters document their extensive reading in their own library. Subjects covered by books in the collection include novels, collections of poetry and folktales, drama, ancient culture, mythology, biographies, and published letters and histories.

1910 Longfellow’s lifelong interest in the works of Dante Alighieri is represented by over 200 volumes by and about the Italian poet, dating from 1568 to after 1909. These range from a tiny pocket set of The Divine Comedy to editions illustrated by Gustave Dore. The Longfellows had an active interest in the anti-slavery movement, both as it unfolded around them and in retrospect after the close of the Civil War. Books in their library reflect this, including Orations and Speeches of Charles Sumner (1850), Stowe’s A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1853), and Wilson’s History of the Rise and Fall of the Slave Power in America (1876-1878).

Children’s literature is represented by over seventy volumes from the 1840s and 1850s. Fanny Longfellow read with her children and supervised their early education. In 1852, she sent a friend a list of books she recommended for her young son, writing, “It is not easy to find very good ones for a young child, & I remember, in my despair, I often thought of writing some myself knowing so well what pleased best my own children. They liked always stories of simple truth, without being spiced with horrors or with fairy fancy, but as they get older their tastes are less innocent.” Works of LongfellowThe historic library includes an extensive group of the poet’s published works. Many were owned by the author, others given by him as gifts to family members, and still more editions were sought out by H.W.L. Dana in the twentieth century. Together they demonstrate the broad appeal of Longfellow’s works and his deliberate marketing, ranging from cheap copies cloth boards to elaborately decorated gift volumes with gilt tooling and edges. Some of these luxury copies are heavily illustrated with artwork by Ernest Longfellow, Birket Foster, and F.O.C. Darley; an 1865 edition of Hyperion includes individually printed photographic illustrations of the European scenes. Longfellow’s work is also represented in translation – Danish, Dutch, French, German, Italian, Latin, and Spanish – with titles including Lied von Hiawatha, Evangelina, and Leggenda d’Oro. Though not a comprehensive bibliography, the twentieth century editions collected by Dana demonstrate that Longfellow’s work remained widely – and beautifully – available, even as his literary reputation diminished. |

Last updated: January 3, 2024