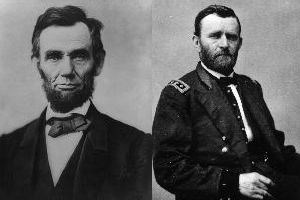

By Timothy P. Townsend, Historian, Lincoln Home National Historic Site "Hold on with a bulldog grip, and chew and choke as much as possible." These determined words of advice were given to General Grant as reassurance and approval of his costly plans for defeat of the Confederate army from a war-weary President Lincoln, just months before the 1864 presidential election that seemed unwinnable at the time. The last year of the Civil War brings to mind a turn in fortunes for the Union and for the retreating Confederate army--of Lincoln planning for reconstruction as General Grant finishes the war by crushing Lee's rag-tag force. What adds an even more fascinating twist to the chain of events is that a national presidential election was held in the midst of Civil War. A work of fiction couldn't be written to match the events of the American Civil War. Especially when one considers the way Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant came together from obscurity to end the nation's bloodiest conflict. This essay will take a closer look at the events that brought these two leaders to prominence and how they worked and thought in concert to achieve their goals--victory in the 1864 election and victory in the war.

Illinois attorney Abraham Lincoln's 1860 election to the presidency was the result of the nation's turmoil. Lincoln was outraged at the passage of the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act. Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas championed this law as a way to end the ongoing debate in Congress on whether to admit states as free states or slave states. According to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the people living in the Kansas and Nebraska territories could decide whether Kansas and Nebraska entered the Union as slave states or free states. This was also known as popular sovreignty. Lincoln opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act because he believed that Congress had already prohibited slavery from these territories. Lincoln saw this, and the Supreme Court's Dred Scott decision, as steps toward the nationalism of slavery. In an autobiographical statement, Lincoln wrote in the third person of his reaction to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, "In 1854, his profession had almost superseded the thought of politics in his mind, when the repeal of the Missouri compromise aroused him as he had never been before." His law partner, William Herndon, described Lincoln as being "astounded," "thunderstruck," and "stunned" when he heard of the Act. Throughout 1855-57, Lincoln traveled extensively giving political speeches. On June 16, 1858, he accepted the Republican nomination to run against incumbent Stephen A. Douglas for the U.S. Senate, and delivered his famous "House Divided Speech" in the Illinois state house: "A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved--I do not expect the house to fall--but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery, will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in course of ultimate extinction; or its advocates will push it forward, till it shall become alike lawful in all the States, old as well as new--North as well as South."

With that speech, the famous Lincoln-Douglas Debates commenced. They included stops at seven communities across the State of Illinois. In November, Lincoln lost the senate race to Douglas, but he later wrote: "I am glad that I made the last race. It gave me a hearing on the great and durable question of the age, which I could have had in no other way; and though I now sink out of view, and shall be forgotten, I believe I have made some marks which will tell for the cause of liberty long after I am gone." Building on the national popularity that he gained in the debates, Lincoln spent the next two years giving speeches throughout the country. Gradually, he began to have the prominence of a presidential candidate. But, Lincoln was not entirely convinced of his presidential potential, although he did admit, "the taste is in my mouth a little." On May 18, 1860 Abraham Lincoln was chosen by the Republican Party to be its presidential nominee. With the Democratic Party split among two presidential candidates and an additional candidate running, Lincoln's presidential election was all but assured. While Lincoln was observing events from his home in Springfield, Illinois during the 1860 campaign, Ulysses S. Grant was clerking at his father's leather goods store in Galena, Illinois.

After having attended West Point from 1839-1843, Grant saw military action in the 1846-48 Mexican War and spent the next several years in mundane service at several remote military outposts. Grant resigned his commission in 1854, and worked a variety of jobs including farming a portion of his father-in-law's St. Louis farm. In 1860 Grant and his family moved to Galena. In his memoirs, Grant wrote of the 1860 election: "It was evident, from the time of the Chicago nomination to the close of the canvass, that the election of the Republican candidate would be the signal for some of the Southern States to secede. I still had hopes that the four years which had elapsed since the first nomination of Presidential candidate by party distinctly opposed to slavery extension, had given time for the extreme pro-slavery sentiment to cool down; for the Southerners to think well before they took the awful leap which they had so vehemently threatened. But I was mistaken."

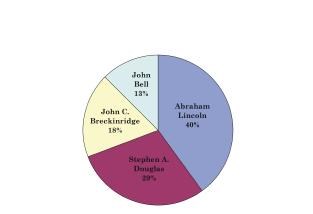

Republican Abraham Lincoln received 40% of the popular vote to northern Democrat Stephen A. Douglas' 29%, southern Democrat John C. Breckenridge's 18%, and Constitutional Union John Bell's 13%. Lincoln left Springfield, Illinois on February 11, 1861 and arrived in Washington, D.C. on February 23. On March 3 he was inaugurated as the sixteenth President of the United States, beginning one of the most difficult presidencies in American history. Even during this time of crisis, Lincoln extended a message of peace in his inaugural address: "I am loth to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearth-stone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature." This last-minute appeal failed to stop the approaching war. On April 12, 1861 southern forces fired upon Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. The fort surrendered two days later. In response, Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 volunteers. The "House Divided" crisis that Lincoln had predicted two years earlier had come to pass. Grant recalled that a company of volunteers was raised in Galena and, while he declined a captaincy, he offered his services by overseeing the company's drill and escorted the group to Springfield. Once at the state capitol, Grant felt that he had completed his duties and was preparing to return to Galena when Illinois Governer Yates convinced him to assist in the Illinois Adjutant-General's office. Grant's military experience came in handy for the state of Illinois and he remained in state service until Lincoln's call for 300,000 more troops in July of 1862. At this time, Grant ended his state service and enlisted in the federal army. Once at the state capitol, Grant felt that he had completed his duties and was preparing to return to Galena when Illinois Governer Yates convinced him to assist in the Illinois Adjutant-General's office. Grant's military experience came in handy for the state of Illinois and he reamined in state service until Lincoln's call for 300,000 more troops in July of 1862. At this time, Grant ended his state service and enlisted in the federal army. Over the course of the next several years Grant steadily moved up in rank. His western theater victories at Fort Henry, Fort Donelson, and Vicksburg won the appreciation and admiration of the nation and President Lincoln. But while Grant was steadily moving up in rank by winning battle after battle, on the eastern front, Lincoln was constantly replacing generals.

In the summer of 1861, General Irvin McDowell led the Union soldiers south from Washington, D.C. with all expectations that it would be a ninety day war. McDowell's devastating defeat at the Battle of First Manassas on July 21, 1861, ended that notion and left Lincoln to search for a new general. Lincoln's next choice, General George B. McClellan, displayed remarkable organizational skill in forming a new army - The Army of the Potomac. Unfortunately, his tactical skill was not as impressive. McClellan's campaign against Richmond, Virginia, although successful in moving the Army within twenty miles of the Confederate capital, ended with withdrawal to the banks of the James River where the advance had begun, and eventually a full withdrawal back to Maryland. After McClellan's failed Penninsula Campaign, General John Pope attempted to take Richmond by advancing, not from the east as McClellan had, but from the north. He failed too. The Confederate General Robert E. Lee defeated him at the Second Battle of Manassas, although Lee had 10,000 fewer soldiers under his command. Against the recommendations of some of his cabinet members, Lincoln re-appointed McClellan to command of the Army of the Potomac. In September of 1862, McClellan successfully defeated Lee at Antietam, although he failed to pursue Lee as Lincoln had wished, causing the President to remove McClellan from command again. On Novemer 7, 1862, Lincoln gave the command of the army to General Ambrose Burnside. Burnside considered himself unfit to command the army, and in practice, this proved true. At the Battle of Fredericksburg, the Union Army reported 13,000 casualties while the Confederates had suffered less than 5,000. In early 1863, the President appointed Joseph Hooker to command of the army. Lincoln wrote him: "I have heard, in such as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the Army and the Government needed a Dictator. Of course it was not for this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who gain successes, can set up dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship." The risk proved relatively small. Generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson handily defeated the Army of the Potomac under Hooker's command at the Battle of Chancellorsville. On June 28, 1863, Lincoln appointed George Gordon Meade to command the Army of the Potomac. Although Meade had achieved victory at the decisive Battle of Gettysburg, his failure to pursue the Confederates as they retreated exasperated Lincoln. In the Spring of 1864, Lincoln made one final change.

In the Spring of 1864, Lincoln had Congress revive the rank of Lieutenant General, a rank last held by George Washington. Lincoln appointed Grant to this rank, and in the summer of 1864, although Meade remained with the Army of the Potomac, it was Grant who now decided the course and tactics of those Union soldiers. Lincoln's promotion of Grant was the culmination of a growing confidence in this general. As early as 1862 when Grant received criticism for the heavy losses at Shiloh, Lincoln responded, "I can't spare this man, he fights!" However, along with saving the Union, there was another issue that Lincoln and Grant considered crucial: the issue of slavery. Slavery, the divisive issue that thrust the nation into the Civil War, remained contenious throughout the conflict, and was very much a part of the national conversation. Both Grant's and Lincon's views on the need for, and timing of emancipation coincided closely. Grant included his views on abolition in a November, 1861 letter to his father: "My inclination is to whip the rebellion into submission, preserving all constitutional rights. If it cannot be whipped in any other way than through a war against slavery, let it come to that legitimately. If it is necessary that slavery should fall that the Republic may continue its existence. Let slavery go. But the portion of the press that advocates the beginning of such war now, are as great enemies to their country as if they were open and avowed secessionists." Lincoln wrote a response to New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley on August 22, 1862, a response almost identical in sentiment to Grant's: "My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union." Early in the war, Lincoln only wanted to restore the Union, but he continued to push for compensated emancipation with colonization. By the summer of 1862 Lincoln told a group of border state representatives: "If the war continue long, as it must, if the object be not sooner attained, the institution in your states will be extinguished by mere friction and abrasion--by mere incidents of the war. It will be gone, and you will have nothing valuable in lieu of it. Much of it's value is gone already. How much better to thus save the money which else we sink forever in the war. How much better for you, as seller, and the nation as buyer, to sell out, and buy out, that without which the war could never have been, than to sink both the thing to be sold, and the price of it, in cutting one another's throats." The border state delegation rejected Lincoln's proposal, but the President was undertaking an alternative course of action. He had already drafted an Emancipation Proclamation that would free slaves in the Confederate States. Lincoln read the proclamation to his cabinet on July 22nd, and one member, Secretary of State William Seward, recommended that he wait for a Union victory. Lincoln took Seward's advice and waited. Lincoln waited two months until September 17, 1862, the bloodiest single day of the Civil War, when the Union forces halted the Confederates at a creek named Antietam. The Confederates retreated south of the Potomac and five days later, Abraham Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. The final one was signed and took effect on January 1, 1863. As with other issues and questions of the war, Grant agreed with Lincoln about emancipation, although he evaluated it with a decidedly military slant. In August 1863 he wrote Lincoln: "I have given the subject of arming the negro my hearty support. This with the emancipation of the negro, is the heaviest blow yet to the Confederacy. The South rave a great deal about it and profess to be very angry. But they were united in their action before and with the negro under subjection could spare their entire white population for the field. Now they complain that nothing can be got out of their negroes." Grant wrote further: "By arming the negro we have added a powerful ally. They will make good soldiers and taking them from the enemy weaken him in the same proportion they strengthen us. I am therefore most decidedly in favor of pushing this policy to the enlistment of a force sufficient to hold all the South falls into our hands and to aid in capturing more." These sentiments, combined with Grant's military successes led to his eventual selection as General-in-Chief by Lincoln. Ironically, the military success that gave him the most prominence occurred at the same time as the Union victory at Gettysburg, although Grant was hundreds of miles away trying to capture Vicksburg. The Vicksburg siege had come at the end of a seven month military campaign. Some criticised Grant, but Lincoln defended him, "Whether Gen. Grant shall or shall not consumate the capture of Vicksburg, his campaign from the beginning of this month up to the twenty second day of it, is one of the most brilliant in the world." On July 4, the day after the Battle of Gettysburg concluded, Confederate General Pemberton surrendered his force to General Grant. The surrender was a stunning victory for the Union: the Federals gained control of the vital Mississippi River, and captured thousands of Confederate soldiers. Following the victory at Vicksburg, Lincoln wrote Grant: "I do not remember that you and I ever met personally. I write this now as a grateful acknowledgement for the almost inestimable service you have done the country. I wish to say a word further. When you first reached the vicinity of Vicksburg, I thought you should do, what you finally did - march the troops across the neck, run the batteries with the transports, and thus go below; and I never had any faith, except a general hope that you knew better than I, that the Yazoo Pass expedition, and the like, could succeed. When you got below, and took Port-Gibson, Grand Gulf, and vicinity, I thought you should go down the river and join Gen. Banks; and when you turned Northward East of the Big Black, I feared it was a mistake. I now wish to make the personal acknowledgment that you were right and I was wrong." Lincoln, well aware of the differences in performance between the eastern and western armies, wanted to place Grant in command of the entire Union Army. Prior to this appointment, however, he wanted some assurances that Grant would not do what his predecessor McClellan was doing--run for the Presidency.

Talk of Grant's candidacy was circulating in both parties and there was some enthusiasm for this successful commander. Following the Vicksburg victory, a Union captain wrote, "The backbone of the Rebellion is this day broken. The Confederacy is divided - Pemberton is a prisoner. Vicksburg is ours. The Mississippi is opened, and Gen. Grant is to be our next president." During late 1863 Grant wrote of this enthusiasm for his potential candidacy: "Nothing likely to happen would pain me so much as to see my name used in connection with a political office. I am not a candidate for any office nor for favors from any party. Let us succeed in crushing the rebellion in the shortest possible time, and I will be content with whatever credit may be given me, feeling assured that a just public will award all that is due." In another letter, Grant wrote: "Everybody who knows me knows that I have no political aspirations either now or for the future. I hope to remain a soldier as long as I live, to serve faithfully any and every administration that may be in power, and which may be striving to maintain the integrity of the whole Union, as long as I do live. . . . Under no circumstances would I use power for political advancement, nor whilst a soldier take part in politics. If, in the conventions to meet, one candidate whos election I would regard as dangerous to the country, I would not hesitate to say so freely however. Further than this I could take not part." Unlike Grant, McClellan did have political aspirations for the presidency. By the fall of 1863 McClellan was making public political statements and endorsements of candidates. He agreed with Lincoln about the need to preserve the Union but did not feel that the slavery issue needed to be addressed. McClellan was courted by the Democratic Party for the 1864 presidential contest and became their candidate while still serving in the army. McClellan found himself in the unique position of being a candidate who felt that the war should be fought to preserve the Union, while running on a Democratic platform that advocated peace, and concluded that the war was a failure. The Democratic platform read, in part, "That this convention does explicitly declare, as the sense of the American people that after four years of failure to restore the Union by the experiment of war . . . the public welfare demands that immediate efforts be made for a cessation of hostilities, with a view to an ultimate convention of the States." The progress of the Union armies slowed following the two victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. A growing weariness of the war and dissatisfaction with its progress developed, and the tenuous alliance of northern war Democrats, abolitionists, and former Whigs that helped to elect Lincoln in 1860 began to unravel. Despite the stress and strain of the office, Lincoln wanted to retain the presidency for another term. When asked about his intentions, Lincoln wrote to Illinois Congressman Elihu Washburne in the fall of 1863: "A second term would be a great honor and a great labor, which together, perhaps I would not decline, if tendered." However, several high profile Republicans were also vying for the presidency, or at least were working for support. These included Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase and 1856 Republican candidate and failed military commander John Charles Fremont. In anticipation of a close election, the Republican Party, to appeal to war Democrats, changed its name to the National Union Party for the 1864 election. The Confederacy was also very interested in the outcome of the presidential election. And, as Grant wrote to one of his commanders in August of 1864, the Confederates also had a preferred candidate: "The rebellion is now fed by the bickering and differences North. The hope of a counter-revolution over the draft or the Presidential election keeps them together. Then too, they hope for a Peace candidate who would let them go. A 'peace at any price' is fearful to contemplate. It would be but the beginning of war." By August of 1864, Lincoln's political insiders advised him that his reelection was in jeopardy. Republican leader Thurlow Weed wrote to Secretary of State William Seward, "I have told Mr. Lincoln that his re-election was an impossibility."

Lincoln seemed to agree that his administration was not going to be re-elected. On August 23 Lincoln called his cabinet together and asked them to sign the back of a sealed document. The document was a memorandum that stated: "This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probably that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so co-operate with the President-elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he can not possibly save it afterwards." The close election demanded attention to every political constituency, especially the Union soldiers. Each individual state determined on their own the process by which soldiers' vote was to be handled. Wisconsin was the first to permit their soldiers to vote in the field through absentee ballots. California, Connecticut, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New Hampshire, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania all followed suit. However, Illinois, Indiana, and New Jersey, which all had Democratic-controlled state legislatures, did not pass legislation allowing soldiers to vote in the field. Likewise Delaware, Rhode Island, Nevada, and Oregon failed to permit absentee voting. Whenever possible in these cases, soldiers were granted leave so that they could return home to vote. The presidential candidates offered the soldiers two distinct choices. A victory for the current Lincoln administration would mean the continuation of the war. A victory for General McClellan, offered the hope for immediate cessation of hostilies and the possibility of permanent disunion. It might seem that the soldiers would rather vote to end the war so that they could return home. But a vote for McClellan would invalidate all of the sacrifices that they and their comrades had made. As one soldier put it, "I can not vote for one thing and fight for another." Another wrote saying, "I do not see how any soldier can vote for such a man, nominated on a platform which acknowledges that we are whipped." What would have been the normal boredom of camp life was stirred up with the coming election. One soldier wrote in his diary "politics keep up quite an excitement on our company." Grant, while supportive of the soldier vote, wrote to the Secretary of War with the following guidelines for the election season, "No political meetings, no harangues from soldiers or citizens and no canvassing of camps or regiments for votes." On August 31, 1864, Lincoln spoke to members of the 148th Ohio Regiment, who were their way home after completing their term of service. In his remarks, Lincoln stressed the importance of their service to protect the American system of democratic government, and at the same time promoted his candidacy for re-election: "We are striving to maintain the government and institutions of our fathers, to enjoy them ourselves, and transmit them to our children and our children's children forever. To the humblest and poorest amongst us are held out the highest privileges and positions. The present moment finds me at the White House, yet there is as good a chance for your children as there was for my father's. Again I admonish you not to be turned from your stern purpose of defending your beloved country and its free institutions by any arguments urged by ambitious and designing men, but stand fast to the Union and the old flag. Soldiers, I bid you God-speed to your homes." Most historians agree that two factors carried Lincoln to victory: first, the progress of the Union military in 1864, especially General Sherman's capture of Atlanta, and secondly, Lincoln's supporters successfully conducted a campaign that portrayed the Democratic platform as traitorous.

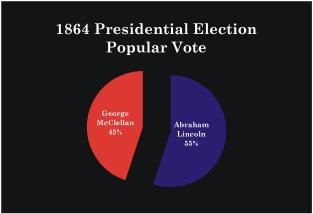

Republican Abraham Lincoln received 55% of the popular vote to George B. McClellan's 45%. The soldier vote only accounted for 4% of the total vote cast. Despite Lincoln's fears in August, he overwhelmingly defeated McClellan in the popular vote by receiving 78% of it compared to 22% for his opponent. Lincoln interpreted his re-election as a mandate that the war should continue with the outcome of reunification of the nation without slavery as the only acceptable result. Following the election, Grant wrote to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton: "Enough now seems to be known to say who is going to hold the reins of Government for the next four years. Congratulate the President for me for the double victory. The election having passed off quietly, no bloodshed or riot throughout the land, is a victory worth more to the country than a battle won. Rebeldom and Europe will so construe it." Grant also wrote that the results would help to end the war and secure the nation's place in the world: "The overwhelming majority received by M. Lincoln, and the quiet with which the election went off, will prove a terrible damper to the rebels. It will be worth more than a victory in the field both in its effects on the rebels and in its influence abroad." The importance of the 1864 election cannot be overemphasized. The fact that during a civil war, when Lincoln could have made a case to retain his presidency without an election, the democratic process continued unimpaired was a testimony to the democratic system of government. The election of McClellan and the peace Democrats would have ended the war, but reversed the progress that was made toward emancipation and the end of slavery. Historian Mark E. Neely Jr., went so far as to write that "Had he [McClellan] won, slavery would doubtless have survived the war, and the history of American racial relations might be a good deal more like South Africa's." Thankfully we can only speculate about Neely's conclusion. Because of the resolve of Lincoln and Grant, two western heroes who were relatively unknown a decade earlier, the war was pushed. They pushed relentlessly with the same vision on two fronts: by Lincoln in Washington, D.C., on the political front and by Grant in the field at the military front. |

Last updated: April 10, 2015