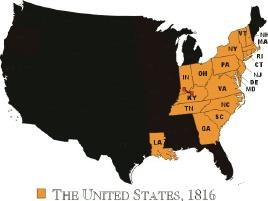

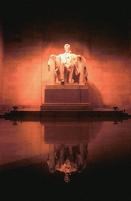

By Timothy P. Townsend, Historian, Lincoln Home National Historic Site Today we most often see Lincoln in the form of larger-than-life statues, such as this one that sits in the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC. Yet through most of his life Lincoln was just one of many frontier boys, or militia members, or attorneys, or, as he was in 1809, just one of many Americans entering the world on the frontier of a young nation. Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809 near Hodgenville Kentucky, in a one room log cabin. It had a dirt floor and no glass windows. Lincoln was the second of three children born to Thomas and Nancy Hanks Lincoln. Lincoln's older sister, Sarah, was born in 1807 and his younger brother, Thomas, who died in infancy, was born in 1812. Abraham Lincoln was the first president born in a log cabin, and the first born outside the original thirteen states. Lincoln's father was a farmer who spent much of his life on the frontier continually pushing west for better opportunities. Lincoln lived with his family on the farm of his birth until 1811 when they moved several miles away to a farm on Knob Creek.

The Lincoln family stayed on the Knob Creek place another five years until December 1816 when they moved approximately 90 miles to the northwest, to southern Indiana. As Lincoln wrote later in life: "This removal was partly on account of slavery; but chiefly on account of the difficulty in land titles in Ky." Abraham, though very young, was large of his age and had an axe put into his hands at once; and from that till within his twentythird year, he was almost constantly handling that most useful instrument -- less, of course, in plowing and harvesting seasons. As for education, Lincoln found that "There was absolutely nothing to excite ambition for eduction" and, as for the teachers, he wrote that "no qualification was ever required of a teacher, beyond readin', writin', and cipherin', to the Rule of Three."

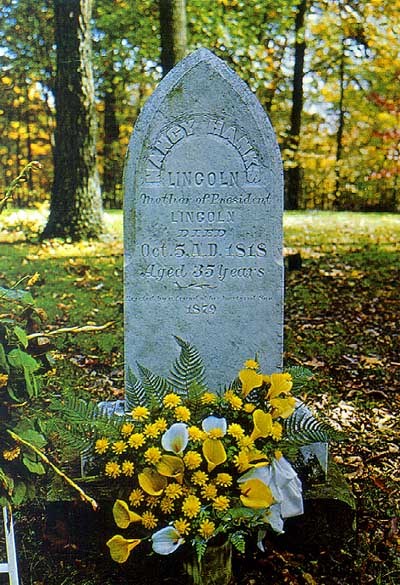

On October 5, 1818, Lincoln's mother, Nancy Hanks, died of "Milk Sickness" an often terminal illness that occurred when one drank the milk from a cow that had eaten a toxic plant -- white snakeroot. Lincoln was only nine years old when she died, and he wrote little about her. When he referred to her in later years, he described her as his "Angel Mother," that is, his deceased mother. The death of Lincoln's mother left young Lincoln and his sister responsible for the great amount of work involved with maintaining a frontier home and farm. On December 2, 1819, Thomas Lincoln married again to widow Sarah Bush Johnston and returned home with his new wife and her three children. "She proved a good and kind mother to A[braham]." The new Lincoln family continued to farm and the children attended school when they could. Lincoln later recalled that he "went to A.B.C. schools by littles" and 'the agregate of all his schooling did not amount to one year." Tragedy again befell the Lincoln family on January 20, 1828 when Lincoln's sister Sarah, who had married Arron Grigsby in 1826, died while in childbirth. Lincoln experienced the death of two close family members within ten years of one another on this harsh frontier. It was also in Indiana that "in his tenth year he [Lincoln] was kicked by a horse, and apparently killed for a time." but, after several minutes, Lincoln regained consciousness.

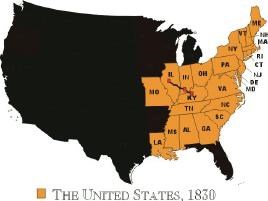

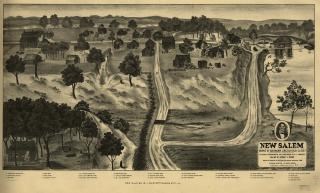

The following year Lincoln again hired himself out to take a flat boat to New Orleans. He completed the trip in July 1831. Upon his return, he moved to New Salem, Illinois to live on his own for the first time. Within a year of Lincoln's arrival at New Salem, he began his political career by campaigning for the Illinois state legislature. But his campaign was interrupted when he joined other volunteers in the 31st Regiment, Illinois Militia, formed to quell an Indian uprising. The company elected Lincoln as their captain and Lincoln later recalled that "he has not since had any success in life which gave him so much satisfaction." Lincoln traveled throughout northern Illinois during his four-month service in the Black Hawk War and had "a good many bloody struggles with the musquetoes; and, although I never fainted from loss of blood, I can truly say I was often very hungry." Upon his return to New Salem in July 1832, Lincoln made a last minute attempt to win the legislative seat but he came in eighth out of thirteen candidates. In 1833 he invested in a New Salem store, with William Berry as his partner. Later that year, he was appointed postmaster of New Salem. In 1834 he took up land surveying and won his first election to public office as a representative in the Illinois legislature. Lincoln was reelected in 1836 and it was during this time, under the persuasion of John Todd Stewart, that Lincoln began to study law. It was also during the New Salem years that Lincoln's first associations with women are recorded. The best known was his relationship with Ann Rutledge. While there are variations, the core of the story consists of the following: Lincoln and Rutledge became romantically involved sometime after Ann's fiancée, a Mr. McNamara, went back east to tend to family business. In the summer of 1835, nearly three years after McNamara's departure, Ann died of what was referred to as a "brain fever," either typhoid or malaria. The degree of Lincoln's grief following Ann's death is debated and ranges from his wanting to be buried with her, to stating that his heart is buried with her, to feeling sad at the loss of a friend. Another, better documented, romance of Lincoln's during this time was his relationship with Mary Owens. Lincoln proposed to Owens in the fall of 1837, but much to his relief she turned him down. She later recalled that "Mr. Lincoln was deficient in those little links which make up the great chain of womans happiness."

While Lincoln didn't have much luck in his romantic life, his political fortunes continued to succeed. In February 1837, the Illinois legislature approved the transfer of the Illinois capital from Vandalia to Springfield. This move was the culmination of intense political efforts by Lincoln and other Springfield area legislators, known collectively as the "Long Nine," all of whom--like Lincoln--were over six feet tall. Lincoln moved to Springfield in April of 1837 and began practicing law with John T. Stuart. He roomed with Springfield merchant Joshua Speed above Speed's downtown store and developed what would become a life-long friendship. For the next several years, Lincoln continued to practice law and was reelected to the Illinois legislature in 1838 and again in 1840.

During this time Lincoln also began courting Mary Ann Todd. Mary was from Lexington, Kentucky and was in Springfield visiting her sister Elizabeth Todd Edwards. Lincoln and Mary became engaged but the wedding was called off on "the fatal first of January," 1841, which threw Lincoln into a severe depression. Lincoln and Mary both stayed in Springfield for over a year, but avoided each other, until mutual friends brought them back together. They courted in secret until the day of the their wedding, November 4, 1842, when they were married at the home of Elizabeth and Ninian Edwards, Mary's sister and brother in law. Lincoln later corresponded to a friend saying "Nothing new here, except my marrying, which to me, is matter of profound wonder."

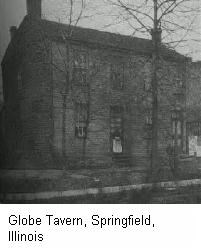

The newlyweds moved into a rooming house known as the Globe Tavern in downtown Springfield. Their first son, Robert Todd Lincoln, was born in the Globe on August 1, 1843. Robert was the only one of their sons who lived beyond the age of eighteen. After Robert's birth, the Lincoln family briefly lived in a rented house in downtown Springfield, and on May 1, 1844 moved into a small 1 1/2-story cottage at the corner of Eighth and Jackson Streets. This would be the only home Lincoln ever owned. Two years later, on March 10, 1846, Lincoln's second son, Edward Baker Lincoln was born. Lincoln continued his legal and political careers and traveled extensively throughout central Illinois on the Eighth Judicial Circuit. As a circuit-riding attorney, Lincoln was better able to make a name for himself as an attorney and politician. Lincoln and Stuart dissolved their partnership in April 1841 and Lincoln formed a partnership with Stephen T. Logan. The firm of Logan and Lincoln continued until 1844, when the firm was dissolved amicably because Logan wished to bring his son into the firm. In 1844 Lincoln became the senior partner of the law firm of Lincoln & Herndon with William H. Herndon. They would continue to actively work as partners until Lincoln's departure in 1861. Although in many law firms the senior partner would receive a majority of the fees, Lincoln operated his firm as a true partnership by splitting the fees equally with Herndon.

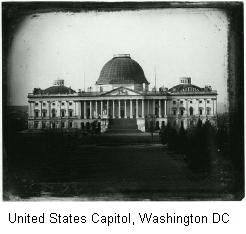

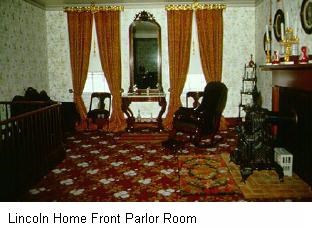

In 1846 Lincoln was elected as a representative in the 30th U.S. Congress. The following year Lincoln brought his family with him to Washington for the beginning of his term. Mary and the boys eventually left Washington in part because Lincoln thought Mary "hindered me some in attending to business." A few months later, however, Lincoln wrote that "having nothing but business - no variety" made life "exceedingly tasteless." Lincoln's term in Congress was fairly uneventful and upon its completion he returned to Springfield and his law practice. In an autobiographical statement, Lincoln later wrote, "Mr. L. was not a candidate for re-election. This was determined upon, and declared before he went to Washington, in accordance with an understanding among whig friends, by which Col. Hardin, and Col. Baker had each previously served a single term in the same District. Upon his return from Congress he went to the practice of the law with greater earnestness than ever before." On February 1, 1850, Eddie Lincoln died of "consumption," probably tuberculosis, after a fifty-two day illness. A funeral service was held in the Lincolns' parlor the following day. Several days later an anonymously submitted poetic tribute titled "Little Eddie" appeared in the Illinois Daily Journal. Many believe it was written by Abraham Lincoln. The sadness at the loss of Eddie must have been lessened somewhat with the arrival of Lincoln's third son, William Wallace, on December 21, 1850. The family greeted their fourth son, Thomas (Tad) on April 4, 1853. Since his 1847-49 term in the U.S. Congress, Lincoln had largely devoted himself to his law practice. He had continued to ride the Eighth Circuit, only now he was able to afford to take the train to many of the county seats. Lincoln became one of the most successful and sought after attorneys in the state and his client list was made up of individuals as well as corporations and powerful railroad companies.

This success led to increased prosperity which was reflected in the Lincoln family home which by 1856 had grown to a full two-story house. It was decorated with some of the most stylish furnishings, wallpaper, and draperies available. The nation's sectional slavery crisis thrust Lincoln back into politics with the 1854 passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. This act allowed the inhabitants of the territories of Kansas and Nebraska to decide the slavery issue through election. This in effect repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had admitted Maine as a free state, Missouri as a slave state, and prohibited slavery in the old Louisiana Purchase Territory above 36° 30'. "In 1854, his profession had almost superseded the thought of politics in his mind, when the repeal of the Missouri compromise aroused him as he had never been before." Lincoln took to the stump and was elected to the Illinois legislature in 1854. He resigned that seat, however, so that he could run for the U.S. Senate. The Senate had long been Lincoln's ultimate political goal. Lincoln, however, withdrew his name from consideration and supported another Whig candidate in order to prevent the election of a rival. Throughout 1855-57, Lincoln continued to practice law, but also traveled extensively giving political speeches. In 1858, he again ran for the U.S. Senate, this time against Stephen A. Douglas. On June 16, 1858 Lincoln accepted the Republican nomination to run against Douglas and delivered his famous "House Divided Speech" in the Illinois state house. "A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved---I do not expect the house to fall---but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery, will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in course of ultimate extinction; or its advocates will push it forward, till it shall become alike lawful in all the States, old as well as new---North as well as South." With that speech Lincoln began what came to be known as the Lincoln-Douglas Debates which included stops at seven communities across the state of Illinois. While Lincoln lost the Senate race to Douglas, he gained valuable exposure that helped propel him to a higher office two years later. He was not convinced of his presidential potential, but admitted, "the taste is in my mouth a little."

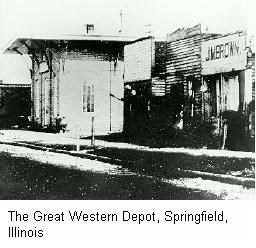

On May 18, 1860 he was chosen as the Republican nominee for the presidency and received official notification of his nomination in his Springfield home. Given that the Democratic party was split with three candidates, Lincoln's presidency was all but assured. Lincoln became the first Republican elected to the presidency on November 4, 1860. He spent the next three months selecting cabinet members, writing his inaugural speech, and greeting numerous well wishers and favor seekers. He also took time at the end of January 1861 to travel to Coles County, Illinois, to visit his father's grave and to see his stepmother, with whom he had an excellent relationship. He had always referred to her as "Mother" in his letters and he wrote of her--"she proved a good and kind mother." Back in Springfield, the Lincoln family packed their belongings and made arrangements to rent out their home during their absence. When finally packed, Lincoln wrapped the trunks and wrote on them, "A. Lincoln, The White House, Washington, D.C."

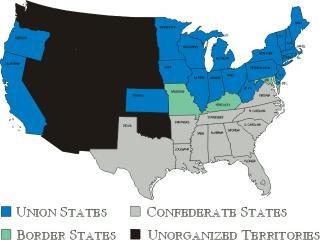

Throughout this hectic time, Lincoln had the weight of the impending crisis of Civil War on his shoulders. South Carolina had seceded from the Union on December 20, 1860. Ultimately twelve states would secede. The Confederacy would include South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Texas, Louisiana, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina. Lincoln's inaugural trip to Washington took twelve days during which he made several stops and public appearances. He arrived in Washington on February 23. On March 3 Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as the sixteenth president of the United States thus beginning what would prove to be the most difficult presidency in history. Even during this time of crisis, Lincoln held out the hope for peace in his inaugural address: "I am loth to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and heath-stone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature." This last minute appeal failed to stop the approaching war and on April 12, 1861 Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina was fired upon by the Confederacy. The fort surrendered two days later. In response, Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 volunteers, the first of many calls that Lincoln would make during his presidency. The "House Divided" crisis that Lincoln had predicted two years earlier had come to pass. Amid the pressures of war and the unending stream of favor seekers, Lincoln found time for his children. His oldest son Robert regularly visited from Harvard College and Willie and Tad were allowed to interrupt meetings at their whim. This was the first time that White House staff had to deal with children in a presidential family and to make matters worse, the Lincolns did not believe in strict discipline. The Lincoln family felt the tragedy of the Civil War in many ways and was especially struck when, on February 20, 1862, their son Willie died in the White House, probably of typhoid fever.

In the summer of 1862 Lincoln had made the decision to issue an emancipation proclamation that would free slaves in the Confederate States. His cabinet suggested that he should wait for a Union victory so that the proclamation did not have the appearance of an act of desperation. On September 17, 1862, what would prove to be the bloodiest single day of the Civil War, Union General George B. McClellan met Robert E. Lee's Confederate forces at Antietam Creek near Sharpsburg, Maryland. The following day, Lee began retreating into Virginia. Five days later Lincoln used his victory as this opportunity to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. The final Proclamation was signed and took effect on January 1, 1863. Lincoln took special pains to write a steady signature so that no one would think that he was not resolved in issuing the document. "And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons."

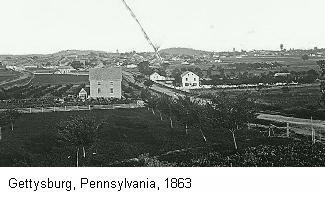

On November 2, 1863 Lincoln received an invitation to give a speech at the dedication of a military cemetery at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. He was not to be the main speaker. Edward Everett was invited a month before Lincoln received his inviation, leaving the President with less than two weeks to prepare his remarks. Lincoln prepared his "few appropriate remarks" in the White House prior to the November 19 ceremony and added some finishing touches in Gettysburg the night before. Following the two-hour oration from the featured speaker Edward Everett, Lincoln rose and gave his two-minute "Gettysburg Address." "Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth upon this continent, a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate - we can not consecrate - we can not hallow - this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us--that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion--that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain--that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom--and that government of the people, by the people, and for the people, shall not perish from the earth." Lincoln returned to Washington feeling that his speech was a failure and responded to a letter from Edward Everett with, "I am pleased to know that, in your judgment, the little I did say was not entirely a failure."

Lincoln had decided that he would run for reelection in 1864. On June 8, 1864, the National Union Party (the temporarily renamed Republican Party) nominated Lincoln as their presidential candidate and on November 8, he was overwhelmingly reelected, defeating former General George B. McClellan. However, the outcome had been in great doubt. Lincoln believed his chances were so poor, because of Union military setbacks and the nation's growing war weariness, that on August 23, he wrote a memorandum, folded it so that the contents were not visible, and asked his cabinet members to sign it. They all did without question. After the election one cabinet member asked about the contents of the memo. Lincoln had written: "This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so co-operate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he can not possibly save it afterwards." By the time Lincoln gave his Second Inaugural Address on March 4, 1865, Union victory was all but assured and Lincoln used the inaugural address to begin to reunite the nation. "With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan--to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations."

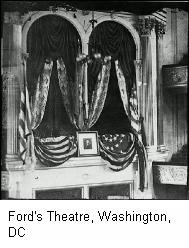

Now that Lincoln had guided the country through the Civil War, he began to concentrate on reconstruction of the Union and life with his family following the presidency. On April 14th he and Mary took a carriage ride and talked of the future. He seemed more cheerful than he had been in a long time. Later that evening Lincoln and Mary attended a play at Ford's Theatre. At 10:30 p.m. southern sympathizer John Wilkes Booth entered the presidential theater box, put a derringer pistol to the back of Lincoln's head, and fired. Lincoln was immediately taken to the Petersen House, a rooming house across the street from the theater. He remained alive for nearly nine hours after being shot, although he was unconscious the entire time. On April 15, 1865, at 7:22 a.m., Abraham Lincoln died. He was the first American president to be assassinated. A shocked nation was thrown into mourning. On April 21, after funeral services in Washington, the Lincoln funeral train, with Lincoln's remains and those of his son Willie, departed Washington and began a 12-day trip back to Springfield. The funeral train reversed Lincoln's 1861 inaugural train route to bring him back home. The citizens of the United States responded with a variety of gestures to express their feelings of grief. Throughout the nation, eulogies were given, poems and songs were written, artwork was produced, and cities located along the funeral train route were draped in black. Each city hoped to outdo the others in its attempt to show the rest of the nation how much it felt the loss of the president. The Lincoln funeral train arrived in Springfield on May 3rd and Lincoln's remains were laid in state in representative's hall of the statehouse, where he had given his "House Divided" speech seven years earlier. At 11:30 a.m. the following day, the Lincoln funeral procession, led by Lincoln's horse "Old Bob," left the statehouse and passed buildings associated with Lincoln's life--including the Lincoln home--on its way to Oak Ridge Cemetery.

Lincoln's remains, along with the remains of Willie, were laid to rest in a temporary vault. The dramatic sixteen day funeral had come to an end. Six years later, Lincoln's, Willie's, and Tad's remains were transfered to a new tomb in Oak Ridge Cemetery. Tragedy continued to befall the Lincolns after 1865. Tad died in 1871 and Mary passed away in 1882. But Robert lived until 1926 and was alive and present in 1922, to witness the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial. And the Lincoln Memorial was just one of many memorials dedicated to the memory of the 16th President. Historic sites, libraries, and museums, including Lincoln Home National Historic Site, receive visitors from across the nation and the world.

|

Last updated: April 10, 2015