Jutting out from rugged sea cliffs lies the flat Kalaupapa Peninsula, one of the most remote locations in Hawai'i on the north shore of Moloka'i Island. Over millions of years, several episodes of volcanic and geologic activity created the peninsula and its towering cliffs. This landscape is one of natural isolation, utilized for over a century to quarantine peoples with Hansen's disease.

An Ever-Changing IslandThe Hawaiian archipelago is a chain of eight major islands, reefs, and shoals extending more than 1,600 miles in the Pacific Ocean. The seven inhabited islands in the southeast end of the chain, from northwest to southeast, are Ni`ihau, Kaua`i, O`ahu, Molokai, Lana`i, Maui, and Hawai`i. The islands were formed by volcanic action, mainly basaltic volcanic domes. Molokai is the fifth largest island of the Hawaiian chain. During the Tertiary Period, two separate islands, West and East Molokai, rose above sea level. As the two islands grew, they gradually merged. Lava from East Molokai filled in the channel between the two islands to create the current configuration. Molokai now measures about thirty-eight miles long by a maximum of ten miles wide. The island’s highest elevation is the 4,970-foot Kamakou Peak. The people at Kalaupapa refer to the main body of the island as “topside” Molokai. Molokai’s north coast faces the ocean with sheer cliffs. Deep, steep valleys were subsequently cut into the cliffs by stream erosion. Protruding from this rugged coastline is the flat, sea-level peninsula of Kalaupapa, cut off from the rest of the island by the massive cliffs. Towering Sea CliffsMolokai’s massive sea cliffs rise to three thousand feet above sea level, making them among the highest in the world. For decades, geologists thought these cliffs were created through wind and water erosion. However, now it is believed the cliffs formed approximately 1 to 1.5 million years ago after the northern 1/3 of Molokai island collapsed into the sea. Rubble deposited on the sea floor from the event extends over forty miles north of the island. As it split, the northern flank broke into large blocks that subsided in different amounts. These formed steps in the submarine slope leading up to the remainder of the island. As the rubble settled, several large fragments remained above sea level, creating three offshore islands, `Ōkala, Mōkapu, and Huelo. The isolated Huelo Island retains original plant species found on Molokai over two thousand years ago, including a rare native loulu palm tree forest.

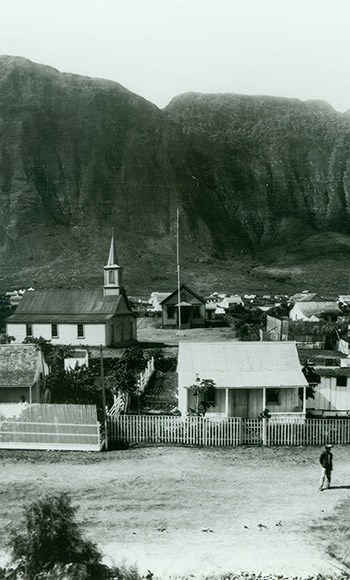

A Stunning LandscapeHundreds of thousands of years following the cataclysmic landslide, which created the dramatic Molokai cliffs, another geologic event occurred. An off-shore volcanic eruption formed the broad flat plain. These two geological events created Kalaupapa's stunning and scenic landscape—the flat, leaf-shaped peninsula against the towering sea cliffs.

The Peninsula FormsGeologists theorize that between 230,000 and 300,000 years ago, long after the extinction of the volcanoes that created the rest of the island, an off-shore shield volcano erupted from the sea floor. This volcano, named Pu'u'uao, formed a relatively flat triangle of land through continuous flows of extremely hot and fast-spreading pāhoehoe lava. The peninsula was formed over multiple eruptions, which built up land from the sea's floor. The land mass, created by the cooled lava, eventually connected with the main part of the island and became the peninsula known today. Kalaupapa translated means "the flat plain." Flying over or looking down from topside Molokai, it becomes clear how the Hawaiian name describes this land. The peninsula is an area of approximately five square miles, 2 miles from cliffs to the tip and 2.5 miles in width at the base of the cliffs. The peninsula's highest point is the Kauhakō Crater, which rises to about 500 feet above sea level. The volcano is now extinct, but the crater remains and is still connected to the ocean by a lava tube. The lake in the middle of the crater has become one of the world's deepest lakes, with a depth of more than 800 feet.

Geology of ImprisonmentSurrounded on three sides by rough ocean waters and cut off from the rest of Molokai by towering cliffs, the Kalaupapa Peninsula has always been one of the most remote places in Hawai’i. In the 1860s, the Hawaiian Kingdom planned to isolate people with Hansen’s Disease and looked to the peninsula of Kalaupapa. Turbulent ocean waters limited places for boats to land. Its natural isolation by the tall cliffs made entry and escape extremely difficult. After visiting in 1889, author Robert Louis Stevenson described the place as “a prison fortified by nature.” On January 3, 1866, the first twelve people were dropped off on the east side of the peninsula. Though they were in advanced stages of the disease, likely having little or no feeling in their limbs and possible blindness, they were expected to create a self-sustaining way of life. In the 103 years that followed, more than 8,000 people living with Hansen’s Disease were sent to Kalaupapa. For those who were taken from their families, friends, and homes, the rolling ocean and towering sea cliffs must have been a constant reminder of their geographic and social isolation imposed on them by a fearful and ignorant world. |

Last updated: December 5, 2022