Kenneth Lingerfelt photo

NPS photo Part of the Park

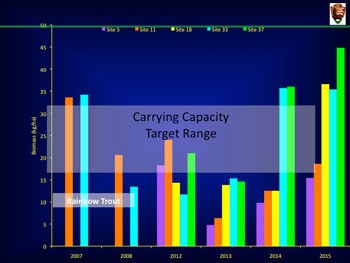

Rainbow trout (Onchorhynchus mykiss) and brown trout (Salmo trutta) were introduced to the park in the early 1900's and 1950's to improve fisheries as a natural resource to the public. Managers were unaware that these non-native species would outcompete and force native brook trout into the uppermost reaches of many southern Appalachian streams, further fragmenting many populations. This decrease in connectivity will lead to a decrease in genetic diversity, which would result in low resiliency to future threats, such as disease, climate change and pollution.

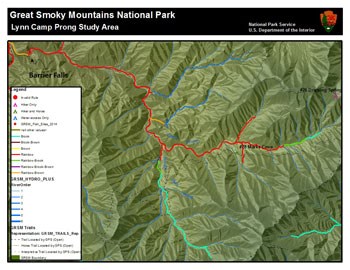

In an effort to follow the park service mission by preserving the remaining southern brook trout and restoring connectivity among populations, removal of non-native species of trout is occasionally necessary. However, this can be an extremely difficult task. A barrier (natural, such as a cascade, or constructed) must be present in order to permanently separate the restored population of brook trout from the non-native species downstream. Cascades, such as the one below on Lynn Camp Prong, provide such a barrier to nonnative fish reinvasion.

Kenneth Lingerfelt photo

NPS photo Restoring Lynn Camp Prong

The Lynn Camp Prong restoration project was developed in 2007 and began in 2008 with the treatment of 8 miles of stream. After encountering some difficulty with uncooperative, hungry bears and illegal stocking of hatchery rainbow trout, the final treatment of the Lynn Camp Prong restoration project occurred in 2011. The park has now restored 11 brook trout populations totaling 27.6 miles of stream. There are another 13 miles of 9 streams that have barriers and may be restored in the future, however the remaining park streams will continue as they are with the species currently present. Currently the population of Lynn Camp Prong brook trout is flourishing as a part of one of the largest native brook trout restoration projects in the southeast. For the first time since the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was established, every stream in the park is open for fishing and harvest, so if you enjoy chasing native brook trout in headwater streams, make sure Lynn Camp Prong has a spot on your calendar!

For more information:

|

Last updated: August 7, 2015