Out of the corner of my eye, a tiny white puff appeared along the horizon. To an inexperienced eye, this sighting would not even register. But with thousands of recorded humpback whale surfacings under my belt and a clear search image, I reflexively began dictating data into my voice recorder – behavior, distance, bearing, observation conditions – and simultaneously focused my laser rangefinder binoculars on the area as the white spout created by the whale faded. Moments later, the whale surfaced again, this time with a bit of its back visible before it lifted its tail and went into a longer, deeper dive from which it wouldn’t surface for another several minutes.

I am a Masters student in the Wildlife Biology Program at the University of Montana, and I partner with the National Park Service (NPS) in Glacier Bay to study humpback whale surfacing patterns around large ships. Over the course of the past two summers, I boarded 78 different cruise ships. As each ship entered Glacier Bay, a small boat brought me and several interpretive rangers alongside and we climbed aboard via a rope ladder. I then spent the day on the bow conducting shipboard surveys for humpback whales, ultimately observing for over 400 hours. The data I collected were added to a decade of research conducted by the NPS.

My head and binoculars are just visible as I observe from the bow. (NPS photo by Janet Neilson)

My head and binoculars are just visible as I observe from the bow. (NPS photo by Janet Neilson)Glacier Bay is a critical feeding ground for humpback whales. The many whales in the Bay provide an amazing viewing opportunity for visitors, but their presence also requires vessel operators to be vigilant and ready to modify their course and speed if a whale is seen nearby. Whales may not be able to pinpoint approaching vessels due to complex underwater acoustics, or they may exhibit delayed responses if they’re focused on caring for young or feeding. It gets more difficult to detect whales as the distance from the ship increases, and the water vapor produced from a whale’s spout dissipates after only a few seconds. Spouts may also be difficult to see, especially if the light is poor or the waves are breaking. Mariners use spouts to locate whales in their vicinity, so understanding whale respiration patterns is extremely important for predicting their behavior and avoiding close encounters and potential collisions.

Heavy raingear was a necessity on most survey days in 2017.

Heavy raingear was a necessity on most survey days in 2017.The goal of our research is to help inform ship operators about the behavior of whales around ships and identify conditions when whales may be more vulnerable to close encounters or collisions. Ultimately, we hope this research contributes to the larger goal of facilitating visitation by cruise ships while protecting important resources like humpback whales. Stay tuned for more information in Spring 2018, when I plan to finish and defend my Masters thesis.

A ship passes through Glacier Bay's Tarr Inlet

I want to extend my deep gratitude to the bridge personnel and crew aboard each of the ships I boarded this summer, as they were a pleasure to work with and were very inspiring in their ability to detect difficult-to-see whales and other wildlife at great distances.

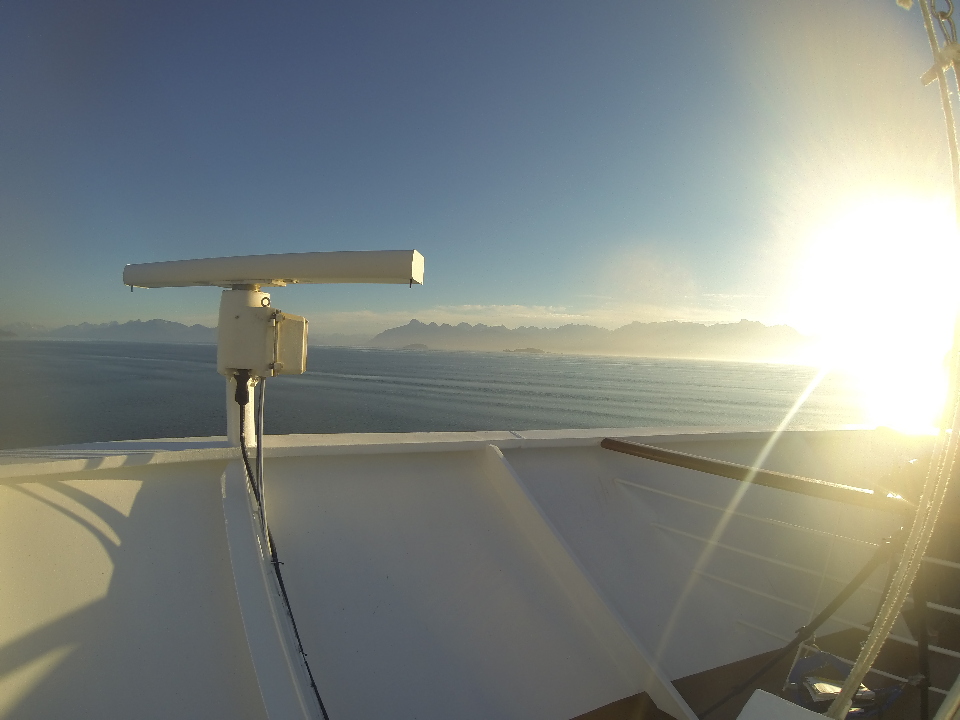

The sun rises as we pass through Sitakaday Narrows

The sun rises as we pass through Sitakaday NarrowsFor related information, below is a link to a publication from a study in Glacier Bay that utilized a similar protocol:

Williams, S. H., Gende, S. M., Lukacs, P. M., & Webb, K. (2016). Factors affecting whale detection from large ships in Alaska with implications for whale avoidance. Endangered Species Research, 30, 209–223.