“Magic,” was Ecologist Lewis Sharman’s simple response when I asked why he has worked at Glacier Bay for 35 years. “I’d always wanted to come here,” he added. “Once I did, I never looked back.”

Not that one could. At least not today, anyway. With a dense fog hugging the ground, looking back was no different than looking forward. Or to the side for that matter.

As a science communicator for the National Park Service, I had boarded the rather stark research vessel Fog Lark at 6:00 am to experience water monitoring in the bay first hand. Seventy-two hours later, weary, wet and chilled to the bone, I staggered off that boat with a notebook full of details and a renewed respect for scientific research… and those who conduct it.

Neither rain, nor snow, nor sleet…research vessel Capelin stands at the ready for whatever conditions Glacier Bay may dole out.

Neither rain, nor snow, nor sleet…research vessel Capelin stands at the ready for whatever conditions Glacier Bay may dole out.For several years the park has been monitoring conditions in Glacier Bay. Their mission? To detect potential changes in the water’s physical and chemical characteristics, and to assess the condition of the microscopic organisms at the base of the food chain. Among other issues, they are concerned about the amount of fresh water entering the ocean from rapidly melting glaciers. Ocean water, being slightly basic, is naturally buffered against ocean acidification. Fresh water, on the other hand, is neutral or even somewhat acidic. As glacial runoff increases, park scientists are concerned that the bay, itself, may become more acidic.

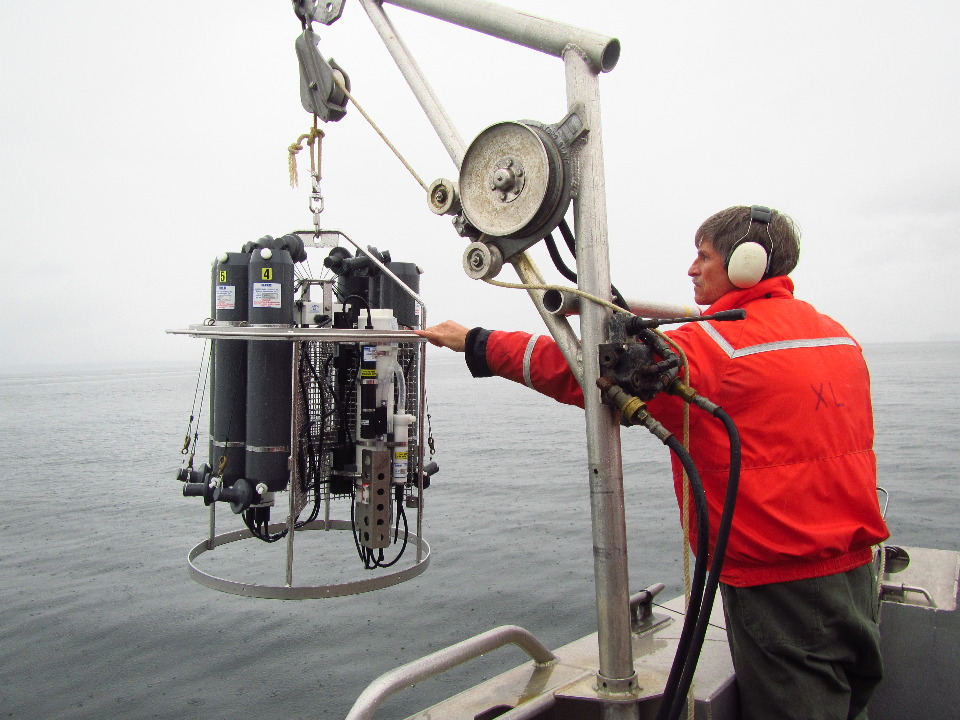

Lowering the conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) probe into the water where it will record water temperature, salinity, and depth as it descends through the water column.

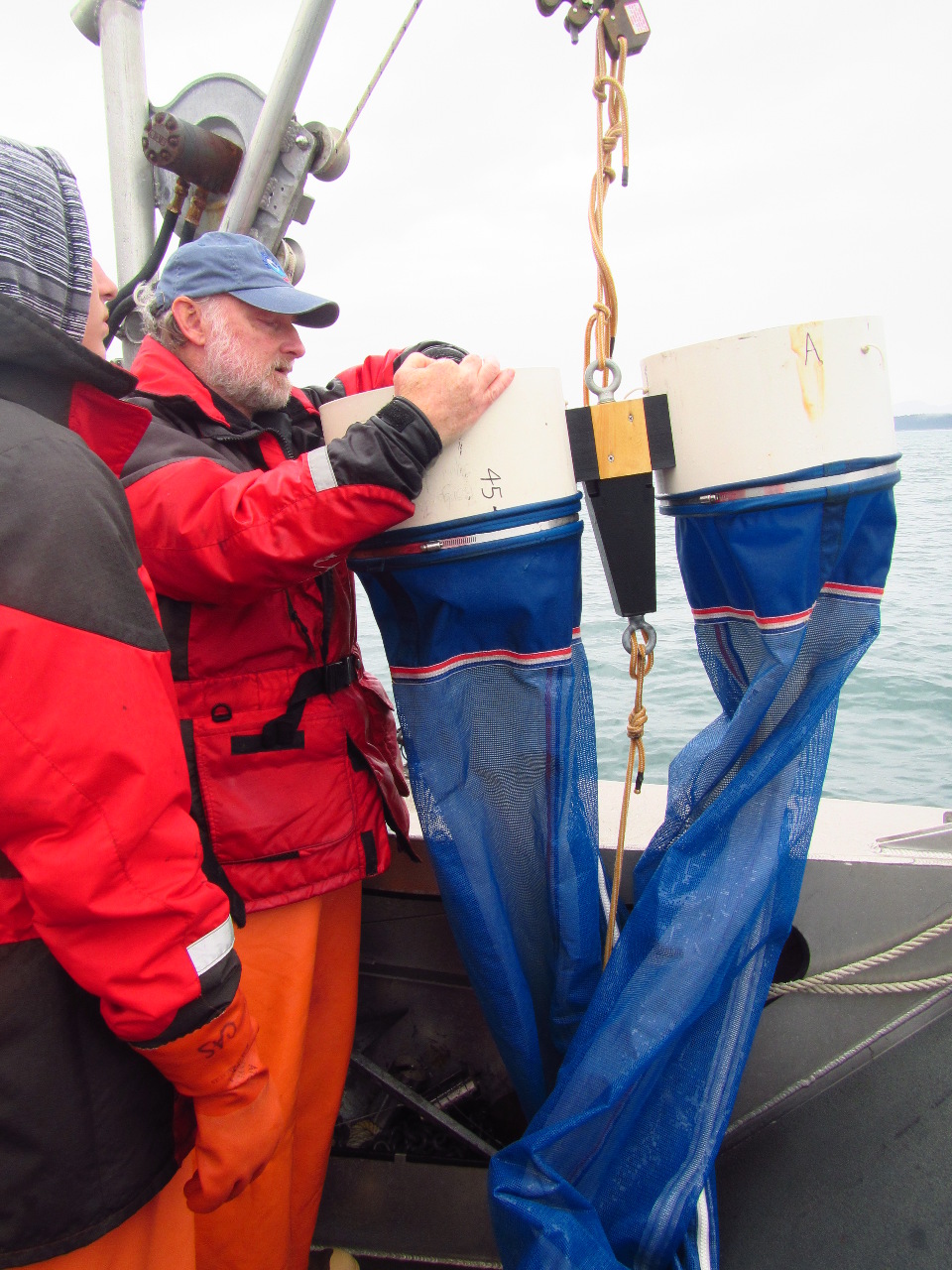

Lowering the conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) probe into the water where it will record water temperature, salinity, and depth as it descends through the water column. Preparing the vertical plankton nets to collect zooplankton.

Preparing the vertical plankton nets to collect zooplankton.So, with a boatload of equipment, four determined researchers and one game, but err….concerned writer (I had seen what was loosely termed our “toilet”), we headed deep into Glacier Bay’s interior where we would collect seawater and zooplankton samples from 22 sites. A specialized probe would measure the water’s chemical and physical properties at various depths at each location. Vertical nets would gather zooplankton samples to be later examined for signs of acidification, such as corrosive pitting in tiny planktonic snail shells.

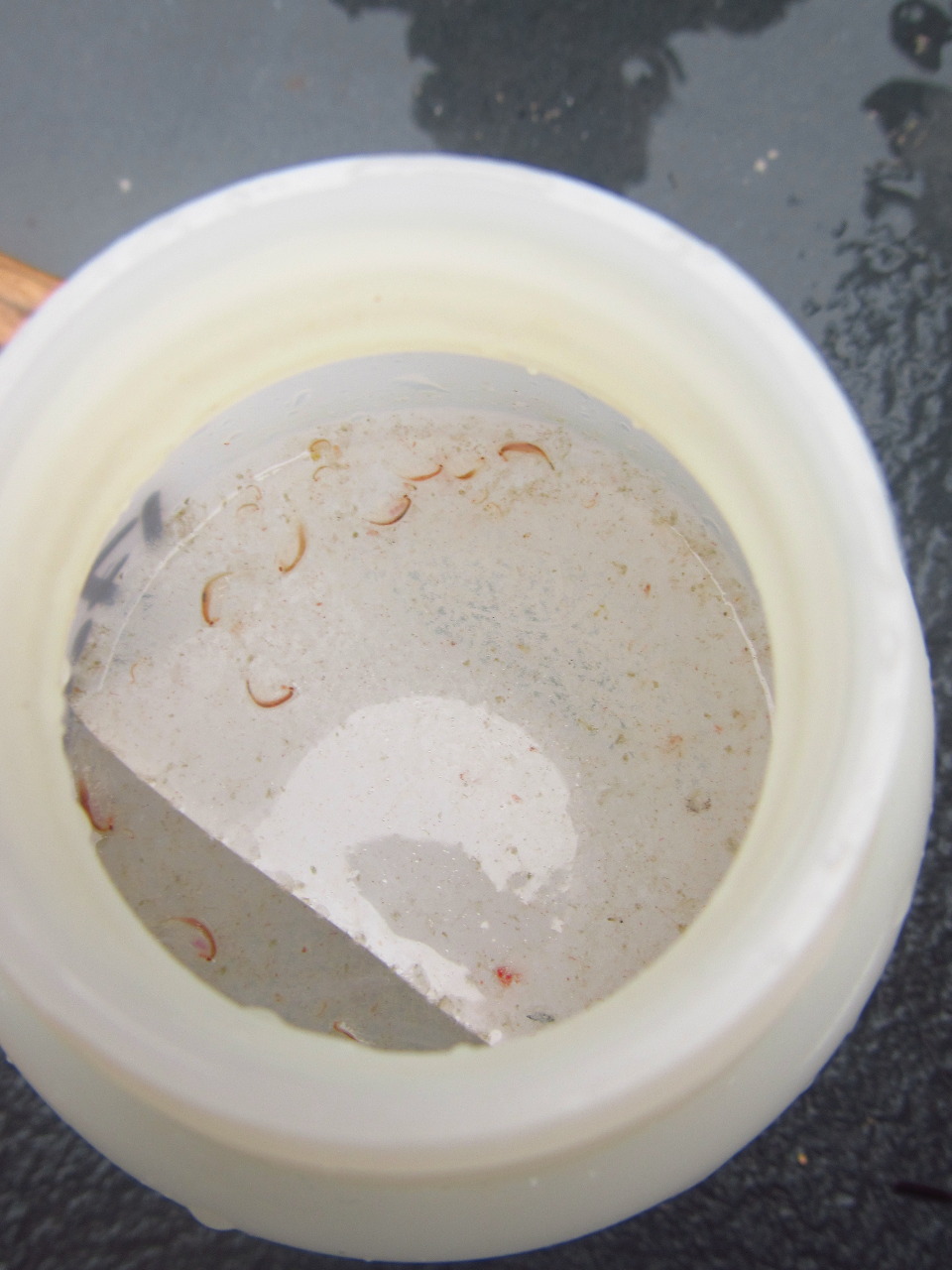

Cup of zooplankton stew anyone…anyone?

Cup of zooplankton stew anyone…anyone?Our work days were long and intense; requiring us to don damp float coats countless times and head out on deck to lower the equipment into the water, haul it back out and draw off water samples. The boat’s tight quarters required constant sidestepping around one another and the supplies that occupied every spare inch. Dreary weather, chilly temps and an occasional driving rain reminded us of our location on the globe; but so did the abundant waterfalls, throngs of seabirds, and the occasional thunder of calving glaciers.

Fog Lark’s hearty crew lowering the CTD probe onto the deck after hauling it out of the water.

Fog Lark’s hearty crew lowering the CTD probe onto the deck after hauling it out of the water.The results of our efforts will be added to the ever-growing set of data from similar excursions, some of which have been taking place since 1993. And, while we may not have been able to see far beyond the boat on this trip, the information we gathered will contribute to a valuable profile of the past, present and future conditions of Glacier Bay seawater. Such insight will help us understand how, and if, the bay is changing and what that might mean to the abundant marine life, and the people, who depend on it.