The common perception of war in American culture is men shooting guns on battlefields. Films such as Saving Private Ryan, Sands of Iwo Jima, and Lawrence of Arabia depict war as a masculine endeavor. Yet war has never only been a man’s concern. History, myths, and pantheons depict women taking leading roles in war across time, space, and the human imagination. History? Joan of Arc, Lakshmibai, Njinga of Angola. Myths? Hua Mulan, the Amazons, La Adelita. Pantheons? Athena, Sekhmet, Parvati. Women—both real and imagined—have taken active parts in war since ancient history.

Sanitation: Modern Cleanliness Standards in WarArmies throughout history suffered from high mortality rates. In the mid-1800s, people—particularly women—finally organized to do something about it. During the Crimean War (1853-1856), high mortality rates in the British Army caused public outrage. The Crimean War was a pushback by the Ottoman Empire, Great Britain, and France against Russian expansion south. Despite Russia's eventual loss, the war was deadly for the British army. When Florence Nightingale, a British nurse, saw the extent of the "constant sickness" and mortality during the Siege of Sevastopol in the winter of 1854-1855, she used statistics to evaluate hospitals from the Crimean War and the earlier Peninsular War (1808-1814). During the Peninsular War, 21% of the army was sick at any given time; during the Siege of Sevastopol in the Crimean War, 38.9% of the army was sick at any given time. And while one batallion during the Peninsular war faced a 33.7% mortality rate during the winter of 1812-1813, certain corps at Sevastopol faced a 73% mortality rate. In the span of forty years, rates of sickness and death had practically—or more than—doubled. Florence Nightingale led the charge to bring modern sanitation into the military. She led a team of British nurses to Crimea to work in the military hospitals there. She was commonly known as "the lady with the lamp" and called a "ministering angel" by the London Times for making hospital rounds in the dark. But her public image as a gentle caretaker hides her other accomplishments. Nightingale was the first person to use statistics to evaluate hospitals, as seen above. Her careful work provided hard numbers for both official and public use. As a woman interacting with military men, she was seen as a nuisance by officers she considered incompetent, as she refused to back down in getting what was needed to improve the lot of British soldiers. Nightingale was awarded an Order of Merit in 1907, but her work during the Crimean War had a far-ranging impact decades before.

Bringing Sanitation to the Union ArmyThe American Civil War broke out on April 12, 1861. For men in the Union, the way to support their country was clear: enlist, and fight. For women, the answer proved vital for all those enlisted men: women worked together to support the army. The Women's Central Relief Association of New York, for example, first met on April 25, 1861 and grew out of varied ladies' organizations. However, their desire to help was stymied by a lack of information. In order to best aid the Union, they needed a direct line to the government. The creation of the United States Sanitary Commission filled that gap in knowledge. The USSC was a private relief agency founded on May 23, 1861 to supplement the unprepared and undersized Medical Bureau. The founders were inspired by the works of Florence Nightingale, the British Sanitary Commission, and women's societies like the Women's Central Relief Association. The Commissioners successfully lobbied for changes to the Medical Bureau to improve conditions for Union soldiers both in sickness and health. On May 23, they asked President Lincoln and his Secretary of War for a draft of powers, in which they said:

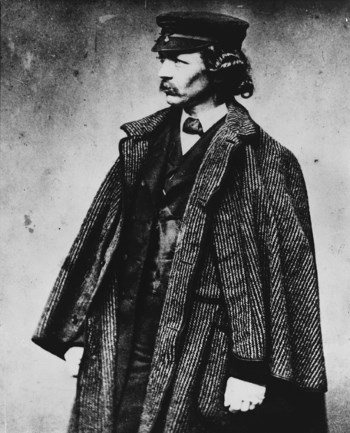

"It is a good big work I have in hand."Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) was best known at the time as the creator and superintendent of Central Park and as the author of an impressive account of conditions in the South. His work on Central Park had gained him national fame as an administrator, and his journalistic writing under the pen name "Yeoman" exposed the horrors of enslavement and what he saw as the uncultured conditions in the South. Unlike many abolitionsists, Olmsted used economic and rational arguments to support abolition, not emotional arguments. When the Civil War broke out, Olmsted was unable to join the army due to the aftereffects of a carriage accident the previous year which left him permanently disabled. But thanks to his well-known experience at Central Park, he was approached to serve an administrative role in the USSC on June 20, 1861. As Resident Secretary, and later as General Secretary, Olmsted coordinated the distribution of donations and USSC personnel throughout the Union Army. These roles were a perfect use of Olmsted's talents to support the Union. His success, and the success of the USSC at large, was possible only with the support of the women he worked with.

Women at Work: "The Fruitful Energy of All"One of Olmsted's collaborators in the USSC was Katharine Prescott Wormeley (1830-1906), an English-born resident of Newport, Rhode Island. She joined the Newport Women's Union Aid Society in 1861 and volunteered for the USSC in 1862. She worked closely with Olmsted in Virginia as a superintendent of nursing, a field she remained interested in for the rest of her life. In addition, Wormeley wrote The United States Sanitary Commission: A Sketch of its Purposes and its Work, a history of the USSC, to raise funds for the organization. After the war, she published a collection of her letters from her time in Virginia as part of the Peninsular Campaign, where she worked chiefly on hospital ships such as the Spaulding. Wormeley and other privileged white women served in leadership roles in aid societies across the Union, but women of all classes played roles in relief efforts. Women and girls sewed socks, knitted scarves, and collected money in support of the USSC in cities and town from coast to coast. California, Massachusetts, and states in between contributed essential funds and supplies to the war effort. Sanitary fairs, organized and run by women, were held across the nation to raise money for the USSC. Art, food, concerts, and more drew crowds across the Union. Similar aid work was done by privileged white women in the Confederacy as well, though not on a scale to rival the work overseen by the USSC. In "'The Finest Kind of Lady': Hegemonic Femininity in American Women's Civil War Narratives," Melissa J. Strong argues that the work done by the upper-class women during the Civil War for organizations like the USSC—in both North and South—played a large role in extending the role of 'femininity' outside of the home and into professions such as nursing and administration.

While Florence Nightingale and the British Sanitary Commission had solid government support at their backs during the Crimean War, the USSC had to fight tooth and nail to provide adequate aid. As the war went on, regional divisions caused tension within the organization. Olmsted was frustrated by his slipping control and by the loss of what he saw as the true reason for the USSC: cooperation across state and regional lines. He resigned as General Secretary on September 1, 1863. And yet...Despite bureaucratic issues and internal conflict, the USSC continued to support the army through the end of the war and only disbanded in May 1866. The Commission's work has had myriad lasting effects. The American Red Cross. Civil War nurse and social reformer Clara Barton (1821-1912) founded the Red Cross in 1881 based on the International Red Cross and the USSC. Women's Suffrage. After the war, many women who had served in leadership positions for the USSC and local women's aid groups went on to join the movement for women's suffrage. Abigail Williams May, head of the New England Women's Auxiliary Organization during the war, served in multiple suffragist organizations afterwards. Olmsted moves to Brookline. In 1883, Frederick Law Olmsted moved to Brookline, Massachusetts to work on Boston's Emerald Necklace. On March 2, 1889, The Chronicle printed a summary of a talk Olmsted gave to the Brookline Club, which explains that "[his] attention was first directed to this town by its generosity during the war. At that time he was in Washington, and learned of the car-load of supplies forwarded to the soldiers by the late Ginery Twichell. With Brookline it seemed to be 'Deeds, not words.'" Olmsted's Brookline residence and office is now the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site. Women's work in the Civil War saved lives. Their work set the stage for women to explore more types of work outside the home while maintaining their femininity. And aid from Brookline inspired Frederick Law Olmsted to make his home and office here at Fairsted, a place you can still visit today. Rebecca Beit-Aharon, volunteer. January 2020.

Interested in learning more. Explore the stories on the History of Women in Landscape Architecture, look Behind the Scenes of the Olmsted Office, and check out this video.

|

Last updated: March 5, 2024