|

The large number of entries in the category of school campuses, which encompasses locations in many places in the United States and Canada, testifies to the importance of educational clients to the success of the Olmsted firm. It also reflects the ever-increasing importance that education came to occupy in American life after the Civil War. Frederick Law Olmsted was of a generation of social thinkers who gave credence to the notion that the physical environment of learning- buildings and grounds- played a significant role in the success of education. Olmsted had planned campuses for the new universities, notably Cornell University and Stanford University; his successors carried on and expanded this sphere of landscape architecture. The names of many well-known colleges and universities, such as Wellesley College, Johns Hopkins University and Princeton University, highlight the list of commissions from institutions of higher education. Together with many private and public universities, the Master List includes public elementary schools and secondary schools, religious and private schools, private preparatory schools, normal schools, liberal arts colleges, women’s colleges, and agricultural colleges. The bulk of the projects in this category date from the first three decades of the twentieth century, the time during which John Charles Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. guided the firm.

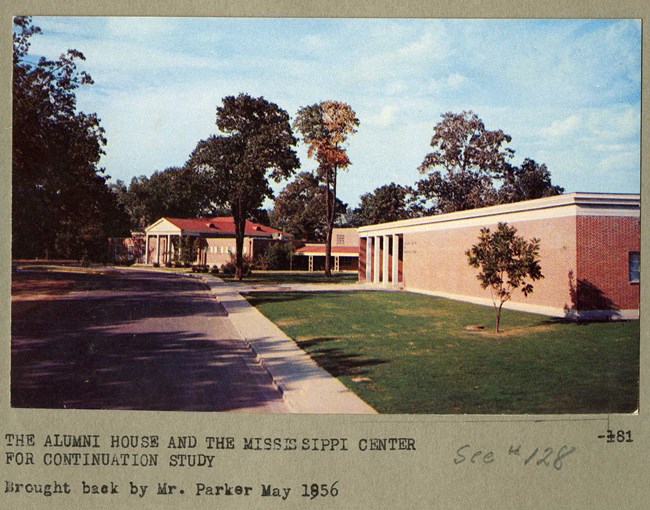

Olmsted Archives University of Mississippi (Oxford, MS)Years before Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. had even begun his career as a landscape architect, the grounds for the University of Mississippi had already been landscaped. Completed in 1848, the campus was made of a parklike octagonal green space, surrounded by institutional structures. Like many successful schools, enrollment increased, and the campus became too small to house its student body.A century later, Olmsted Brothers were hired to develop a plan for the now 640-acre campus to accommodate future enrollment of over five thousand students. Firm member Carl Parker was tasked with overseeing the work at Ole Miss, where he established an east-west axis along a central ridge of the campus. The design was meant to honor the original plan with a series of open quadrangles, all connected through green paths. Parker chose to relocate roadways and parking areas to the periphery of the campus, allowing the pedestrian-oriented core to dominate. Olmsted Brothers planting plan emphasized placing varieties of dogwoods, oak, and fruit trees across the campus. For nearly forty years through Olmsted Brothers and into Olmsted Associates, the firm remained involved at the University of Mississippi.

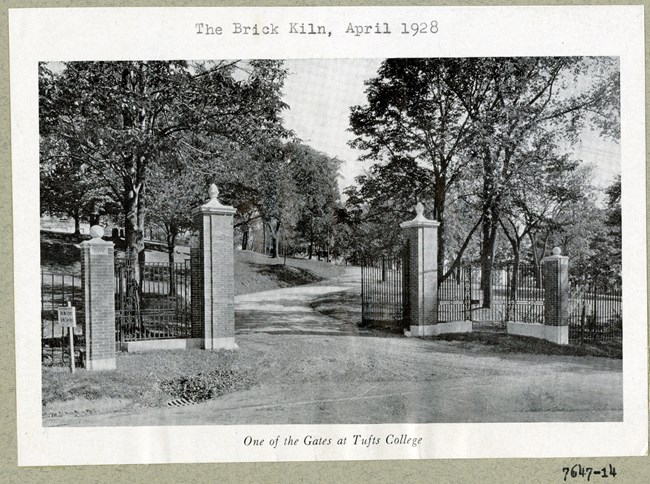

Olmsted Archives Tufts University (Medford, MA)Olmsted Brothers were hired by Tufts University in the 1920s to consult on the growth of the campus. The school had grown from a small liberal arts college to a top-tier research university, housing a significantly larger student population.Led by Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., he brought to Medford the classic Olmstedian ideals of landscape architecture, spearheading the design of Memorial Steps as well as the surrounding area. Olmsted Jr. recommended unused lots along the hill behind Ballou Hall be preserved for open green space. Olmsted Jr.’s 1920s plan would shape the campus for the next fifty years. Dorms were grouped around campus greenery, making it feel less like a campus and more like a community. The plan also included a teaching hospital for the medical school., which would later be relocated to Boston. For many years, Olmsted Brothers served as managers of Tufts campus grounds, even hiring the University’s first full-time buildings and grounds employee.

Olmsted Archives Iowa State College (Ames, IA)Olmsted Brothers were hired by Iowa State College in 1906 to give recommendations on the campus layout and design. The number of students attending Iowa State had grown immensely since it opened its doors nearly 50 years prior, even more so in the last 10 years.The student body had consisted of about 300 ten years prior but when Olmsted Brothers were brought on, that number had increased to nearly 1,000, and the campus needed additional buildings and space for the increased size. Olmsted Brothers recommended modifying the location of campus roads to create a more pleasing aesthetic. This potential change upset many in the campus community, with an appeal from Iowa State’s alumni stating that “this change from the natural or English-park style so carefully planned, and tried for nearly forty years on our grounds, to the formal or French style, so artificial and as we believe so unsuited”.

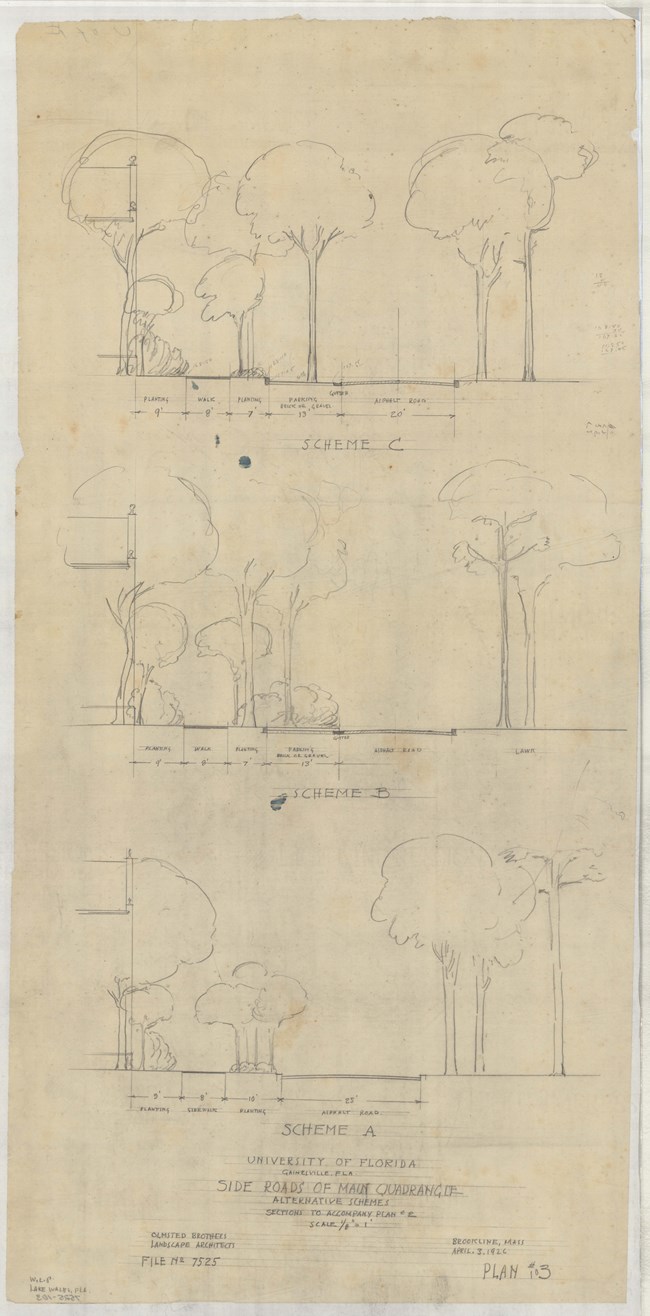

Olmsted Archives University of Florida (Gainesville, FL)The campus design at the University of Florida was born from an ongoing expression of social and architectural change within a context of architectural compatibility. The campus character can be broken into three historical eras. The first era, from 1905 to 1925, was around the implementation of the original campus plan. The second era, from 1925 to 1944 was based on coalescence and enhancement, which was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.Olmsted Brothers was responsible for redesigning and unifying the campus through a planting plan of native vegetation. In 1925, University of Florida hired Olmsted Jr. and firm member William Lyman Phillips to lead the re-design of the campus, specifically to improve the landscape of the quadrangle. The quadrangle, which Olmsted Brothers referred to as the campus green, was the focal point of the early campus and was designed to serve as an entrance to the University. In 1931, the campus green was renamed the Plaza of the Americas, to honor the University hosting the first meeting of the Institute of Inter-American Affairs. Additionally, 21 live oak trees were planted on the Plaza of the Americas, with 21 flags to represent the attending nations.

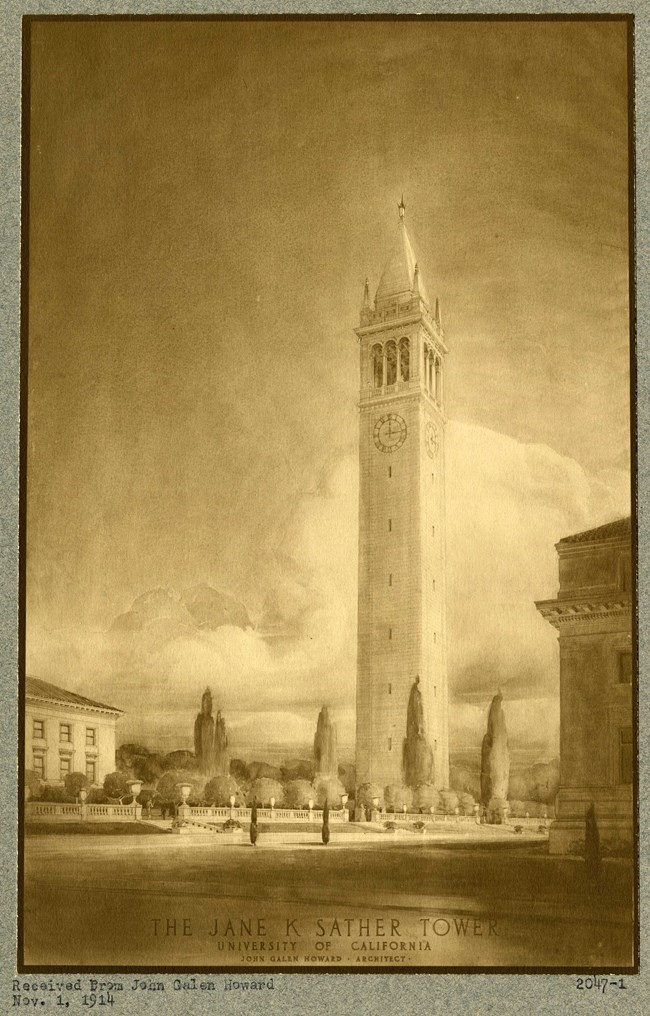

Olmsted Archives University of California, Berkeley (Berkeley, CA)While in California managing the Mariposa Estate gold mine, Frederick Law Olmsted asked in 1865 by the trustees of the College of California to draw up a plan for a campus and residential area on grounds that were once used as a farm. After visiting the site in the foothills of San Francisco Bay, Olmsted proposed a plan where students live in cottages arranged in a picturesque style, with meandering roads and paths around them.Olmsted envisioned a divided roadway curving through the base of surrounding hills, lined with private residences with landscaped grounds. The 1886 “campus park” plan established an east-west axis and characterized by the sloping terrain of the area. By integrating the campus into the surrounding community, Olmsted believed students would benefit from a balance between “a suitable degree of seclusion and a suitable degree of association” with the rest of the world. One of Olmsted’s first campus plans, it was not implemented by Berkeley’s founders, though it would form the basis for Olmsted’s ideas on campus planning. Olmsted would depart from more traditional, symmetrical campus designs that he felt weren’t conducive to growth and expansion. As with his parks, Olmsted designed with the future in mind.

Olmsted Archives Stanford University (Palo Alto, CA)When Leland Stanford Sr.’s son died of typhoid fever at the age of 15, the railroad tycoon felt the best way to honor his son would be to dedicate a new college in his honor. Stanford wanted the best, so for the grounds of his campus, he hired Frederick Law Olmsted.From his arrival in the Fall of 1886, Olmsted’s relationship with Stanford would be a tumultuous one. From the selection of the site to determining the orientation of the main quadrangle, Stanford was involved in every major decision on the campus. Stanford wanted his school to rival those of New England’s Ivy League campuses, however Olmsted proposed a campus uniquely suited to California’s climate. Stanford dictated much of Olmsted’s design work on the project, envisioning a campus monumental in scale and formal in design, while Olmsted proposed a campus nestled into the hills around the property. However, Stanford insisted the campus be built on flat land, with a grand axial approach in the center of campus. As a strong-willed client, and putting in $30 million to the design, many of Stanford’s ideas were largely implemented. Nevertheless, Olmsted won a key disagreement when he proposed the main campus quadrangle be paved and contain plantings of native trees and shrubs. While Olmsted’s vision of open, interlocking quadrangles was gradually lost due to campus development, the quad design illustrates a key Olmsted principle-sustainability. Olmsted's recommendation of paved space and native plants over lawns showed an understanding of the resources needed to maintain a landscape.

Olmsted Archives Huntingdon College (Montgomery, AL)When the campus of the Tuskegee Female College would no longer suffice for a growing campus, it was decided to move the college, which would be renamed the Women’s College of Alabama before becoming Huntingdon College, to the more populous, urban environment of Montgomery.Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. would begin creating plans for Huntingdon in 1908, though he would not oversee its implementation. Given 58 acres to work with on what was then the outskirts of Montgomery, Olmsted Jr. 's plan would create a beautiful campus on rolling hills, with a natural amphitheater and lush greenery.

Olmsted Archives Phillips Academy (Andover, MA)In 1891, Phillips Academy was going through a period of expansion and reached out to Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. to develop a master plan for the campus, connecting it with the new cottage-like dormitories. It was John Charles Olmsted who would respond to that initial request, and he was joined by Olmsted Jr, and firm assistants Herbert j. Kellaway and George Gibbs.The Olmsted firm developed a plan that would allow for campus expansion west of Main Street, integrating academic and residential areas with gently curving walks that responded to the natural topography of the campus. The work that began in 1891 would carry over five decades, with projects of diverse size and purpose, but always being respectful of the historic character of the land while ensuring an aesthetically cohesive campus plan as a learning environment. The Olmsted’s advised on the locations of buildings like the heating plant, archaeology museum and gymnasium, as well as the grading and planting of roads and paths. In 1908 John Charles took a step back from Phillips Academy, with the project now being supervised by firm member Percival Gallagher. While in charge, Gallagher sited new academic buildings and dormitories, an infirmary, and gave advice about tree care. Over many decades, the Olmsted firm would refine and expand the campus landscape as it grew.

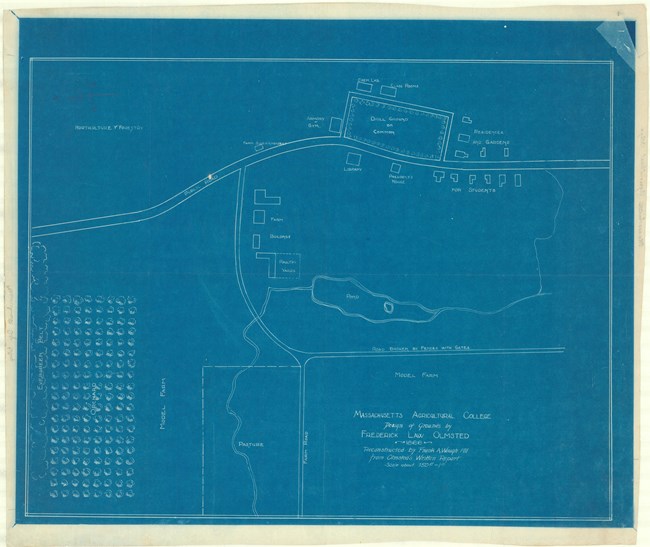

Olmsted Archives Massachusetts Agricultural College (Amherst, MA)When the Lincoln Administration passed The Morrill Act of 1862, it required all states to provide public lands for Land Grant Colleges. The Morrill Act promoted the “liberal and practical education of the industrial classes for the benefit of Agricultural & Mechanical Arts.”In 1864, six Amherst farms of 310 acres were purchased for the site of the new Massachusetts Agricultural College. In 1866, the board of Trustees for the future college asked Frederick Law Olmsted to submit a proposal for the campus and some buildings. Instead of siting the building as requested, Olmsted recommended that the entire college be located on the Eastern slope and be modeled after a typical New England village. Olmsted believed that “the individuality of an agricultural college lies in its agricultural setting, not in its buildings, which is a mere piece of apparel to be fitted to the requirements of the agricultural trunk. In his report, Olmsted recommended that a village green be constructed at the center of the farmland campus. This was the only recommendation of Olmsted’s the Board of Trustees took; they viewed his response to building placement to be an improper response to the assignment and fired him. The Board of Trustees then chose to site the college on the Western plateau. Olmsted’s vision for a Campus Pond and its extensive surrounding lawns was accepted and is a great example of the early use of ecological principles in landscape architecture as well as a central gathering place and focus feature of the campus.

Olmsted Archives Vassar College (Poughkeepsie, NY)In August of 1868, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux made a visit to Vassar College, to begin consultation on the campus's design. A day after their visit, Olmsted wrote to his wife Mary, reporting that “they have a miserable plan to be amended, that’s all.”For the next 65 years, past the time of Olmsted Sr. and into Olmsted Brothers reign, Vassar periodically called on the Brookline based firm for their professional guidance in the expanding campus plan. Of the two Olmsted Brothers, John Charles took the lead at Vassar College, but it was Percival Gallagher, partner at Olmsted Brothers, who contributed most to the college. Taking over from Beatrix Farrand, Gallagher served as consulting landscape architect to Vassar from 1929 to 1933. In addition to adding to the growing arboretum Farrand had started, Gallagher also suggested that the intersections of diagonal walks along the campus quad, collections of Japanese Maples should be planted. Gallaghers suggestion was approved, and one can still walk along the Japanese Maples today.

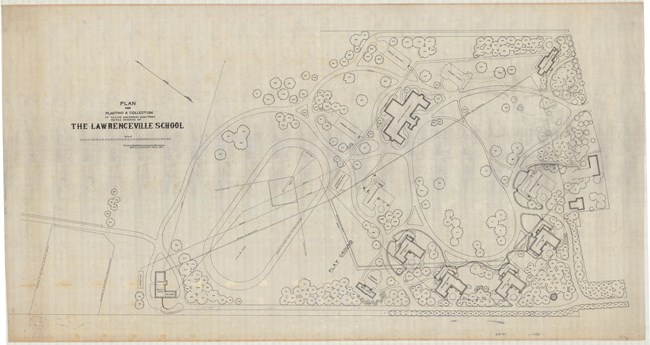

Olmsted Archives Lawrenceville School (Lawrenceville, NJ)One of the first preparatory boarding schools in the United States, Frederick Law Olmsted was hired by Lawrenceville School’s board of trustees in 1880 to create a master plan for the school. Olmsted’s goal was to foster a vibrant academic community in a parklike setting.As always, Olmsted worked closely with the architects on the project, this time Peabody & Stearns, to choose an appropriate place for the dozen school buildings. The plan for the all-boys boarding school was inspired by great English institutions, with buildings arranged around a central green. At Lawrenceville School, Olmsted created a living museum for students, with 371 different species of trees planted throughout the landscape. Many of the trees Olmsted planted were only four to five feet tall and were left over from his work at the Arnold Arboretum. Olmsted was in constant contact with the headmaster at Lawrenceville, sending him various letters during the planning and execution of the design. In the 1920s, Lawrenceville expanded to accommodate its growing population. Olmsted Brothers served as the consulting landscape architects at that time. A walk around Lawrenceville School today will still show you Olmsted Sr.’s original vision.

Olmsted Archives Middlesex School (Concord, MA)The founder of Middlesex School, Frederick Winsor, was a close friend of then Harvard President, Charles Eliot. Eliot’s son, also Charles, was a member and partner in the Olmsted Firm and a protégé of Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. After young Eliot’s untimely death, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. took over as a partner and in 1901 this new firm, Olmsted Brothers, was awarded the contract to design Middlesex School.Creating over three hundred drawings for Middlesex School, Olmsted Brothers began by experimenting with a figure eight design for the central campus. In the end, the Olmsted Brothers chose an oval to design the campus on. To this day, campus development has kept intact the Olmsted Brothers’ original design.

Olmsted Archives Louisiana State University (Baton Rouge, LA)When Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. drew up his campus plan for Louisiana State University in 1921, he did so with the belief that his plan would accommodate 3,000 students. Olmsted’s plan tied the existing trees, topography and features together by establishing a cruciform-shaped quadrangle at the center of campus.For unknown reasons, Olmsted Brothers were dropped from the project, and architect Theodore Link took over. While Olmsted Brothers had originally envisioned a Spanish or Mexican style design for the university, Link designed the campus with stucco walls, red-tiled rooftops, and extensive porticoes to emulate the Italian Renaissance style. Despite dropping the Olmsted Firm, the plan they had created for LSU was meant to be expanded, which is exactly what Link and future landscape architects did. To this day, the campus remains faithful to the Olmsted Brothers design.

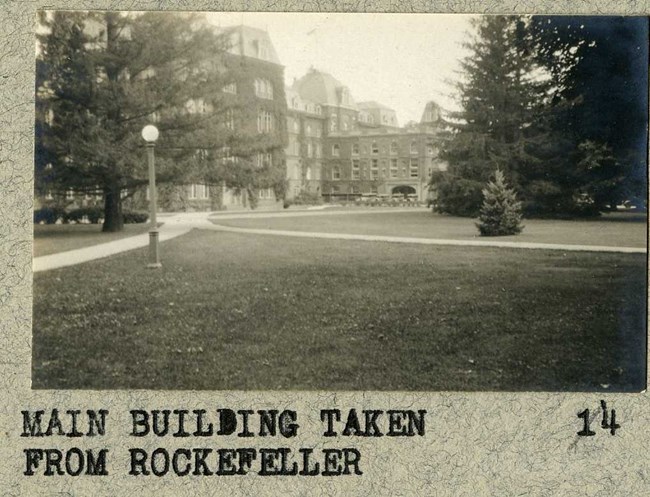

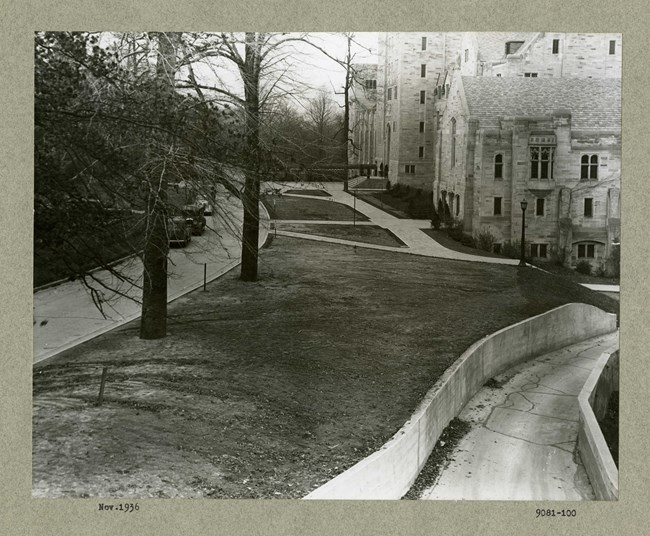

Olmsted Archives Indiana University (Bloomington, IN)Starting in 1929, Indiana University hired Olmsted Brothers to help in the planning and development of their campus. Working at the University for a total of seven years, Olmsted Brothers developed 161 plans for the campus.In a June 1936 letter to Indiana University’s Board of Trustees, Olmsted Brothers sent photographs of two models done for schools, one for Phillips Andover Academy, the other for Phillips Exeter Academy. Olmsted Brothers believed the University could seriously benefit from studying the model, particularly regarding the future development of the campus. Olmsted Brothers wanted the University’s trustees to understand how much easier it would be to experiment with models when deciding sites for new buildings, specifically its size, form, and character. Models allowed everyone to visualize the problem, leading to conclusions with clearer understanding. After having already placed some buildings on campus, Olmsted Brothers noted that had a model been available, they likely would have chosen a different site, one less crowded. Olmsted Brothers also encouraged the University to place a potential model in a highly trafficked part of campus, so people would frequently see it, and get enthusiastic about the new design. Though Olmsted Brothers warned Indiana University that purchasing a model may seem like a large expenditure, one could reasonably call it insurance for the development of a well-organized and efficient plan.

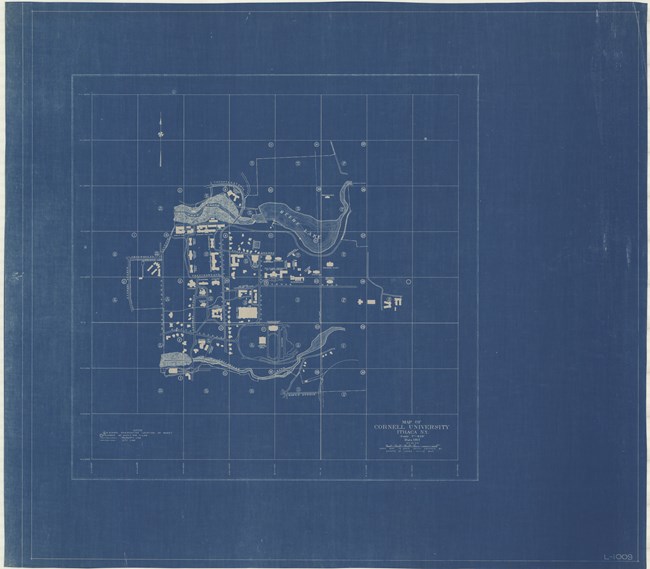

Olmsted Archives Cornell University (Ithaca, NY)In 1685, Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White joined together and founded Cornell University. By May 1867, Cornell and White were disagreeing on what their campus should look like, and so White contacted Frederick Law Olmsted to consult on the appearance for a new campus.Cornell pushed for a design around a quadrangle, which Olmsted recommended they abandon. Olmsted urged the University to lean towards a freer disposition with the buildings. Olmsted didn’t want to fight with the rugged topography of the site but rather worked it into his plan. As with many of his designs, Olmsted predicted that Cornell University would continue to grow, and that the campus they made today needed to handle the unforeseeable demands of later generations. As is sometimes the case, Olmsted’s recommendations came in too late, as planning was already underway with Ezra Cornell’s plan around a quadrangle. After learning the building site he recommended wasn’t chosen, Olmsted wrote to White stating “The site of your second building having been determined against my judgement, it seems to me to be very important that nothing should be done which shall make the suggestion which I offered to you in regard to a terrace impracticable”.

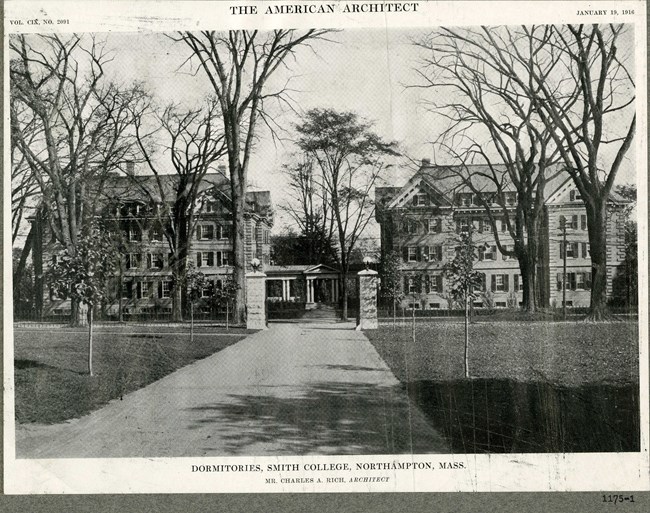

Mr. Charles A. Rich, Architect Smith College (Northampton, MA)In 1891, Smith College Trustees began planning to beautify their campus, while also developing a scientifically organized botanic garden, to serve the new botany department established the year before. They brought in Frederick Law Olmsted to turn the entire campus into an arboretum.Smith College was only twenty years old when Olmsted delivered his first set of plans the following January. Olmsted formed the upper campus in an irregular circle of buildings, which he approvingly characterized as “informal and unpretentious…irregular [and] homelike”. Olmsted’s views were formed by the New England village setting he grew up in, and when laying out any college campus, he proposed a “domestically scaled suburban community, in a park-like setting”. The founders of Smith shared these views, wanting curved lines, open spaces, and diverse plantings. There were several arguments on what would be included in the final design, and after going behind his back and hiring a young botanist to procure all the plantings, correspondence between Olmsted and Smith College stopped. In 1897, when the need for expansion became too pressing a matter to ignore, Smith College again reached out to Olmsted, this time, John Charles, and Frederick Jr. Olmsted Brothers was now faced with the difficult task of putting more buildings on a college campus that had grown in every way but acreage. In one of their final correspondences with Smith College, Olmsted Brothers warned against clipping shrubby, instead encouraging it to grow wild.

Olmsted Archives Columbia University (New York City, NY)Charles McKim of McKim, Mead & White, was chosen to design Columbia’s master plan. Because landscape architecture was such a new profession, many of these brilliant minds ended up working together quite often. McKim had apprenticed with Olmsted Sr.’s close friend H.H. Richardson for two years before leaving in 1879 to work with Mead and White. Olmsted Sr. had already worked with McKim at the World’s Columbian Exposition, where the two had introduced the City Beautiful movement to America with well-designed and maintained grounds. Olmsted Jr. would also end up working with McKim again, when in 1901 they were both chosen to serve on the Senate Park Commission, which would redesign the core of Washington, D.C. The two Harvard alums would also go back to do improvement on their alma mater, with McKim carrying out Olmsted’s plan. Olmsted Sr. noted of McKim’s design that “these courts and quadrangles are entirely cut off one from another, they are entirely independent of each other” -Frederick Law Olmsted Papers: School Buildings and Grounds, Columbia University (1893). McKim’s entire campus was a rectangular, symmetrical design that conforms to the natural topography of the site while taking advantage of the campus’s high position in New York. Olmsted trusted McKim in his arrangement of the campus, praising McKim’s ability to remove trees and replant them in more favorable locations.

Olmsted Archives John Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD)When entrepreneur and philanthropist John Hopkins donated money for both a university and a hospital, he likely knew the medicinal benefits the hospital provide. Hopkins never knew the health benefits his University would provide to students, thanks to Olmsted Brothers. In 1904, Olmsted Brothers were asked to design a myriad of plans for the University, which they worked on till 1917. The plans established two quadrangles for the campus, as well as grading around academic buildings. In their 1904 report, Olmsted Brothers proposed dividing the University’s large land, keeping most for the campus, but others to be used as parkland. The University agreed with Olmsted Brothers, which is why you can find Wyman Park walking distance from campus. Olmsted Brothers identified Wyman Park as one of the finest single passages of scenery so close to a major city they had ever seen. With Olmsted Brothers adding more green space on campus, as well as another retreat off campus, both the hospital and the university at John Hopkins provides good health and wellness.

00058-01 Olmsted Archives University of Chicago (Chicago, IL)In 1902, Olmsted Brothers was asked to revise early campus plans to include a quadrangle. John Charles and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. recommended pathways leading to the center of campus, providing small vistas to University students and faculty. They also collaborated with John Coulter, the first chair of the University’s botany department, on a botany pond. Both Olmsted Brothers and Coulter were bringing lush flora into the campus and felt the botany pond would not only serve as a serene place for students, but a scientific corner to observe the life cycles of plants and animals. Though the botany pond would not get official botanical garden designation until 1997, it reflects a guiding ideal that Olmsted Sr. taught to all who would listen. That “the enjoyment of scenery employs the mind without fatigue and yet exercises it; tranquilizes it and yet enlivens it.” Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. quite literally paved the way for his sons to help plan the University of Chicago; Jackson Park, Washington Park, and the Midway Plaisance, all done while Olmsted Sr. was working on the Columbian Exposition, are walking distance from the University. Specifically looking at the Midway Plaisance, University of Chicago plans to widen the pedestrian paths to create well-lit spaces that invite people into the Midway to appreciate Olmsted Sr.’s work. Olmsted’s original plan for the Midway incorporated more bridges, and the restoration work being done will reinforce that concept. If we look at Olmsted Brothers work at the University of Chicago and Olmsted Sr.’s work on Chicago’s parks for the Columbian Exposition, the similarity is that, despite enduring for years, there are still improvements to be made. With the continued restoration of both these landscapes, old visions unable to completed during the Olmsted’s lifetimes are finally being realized.

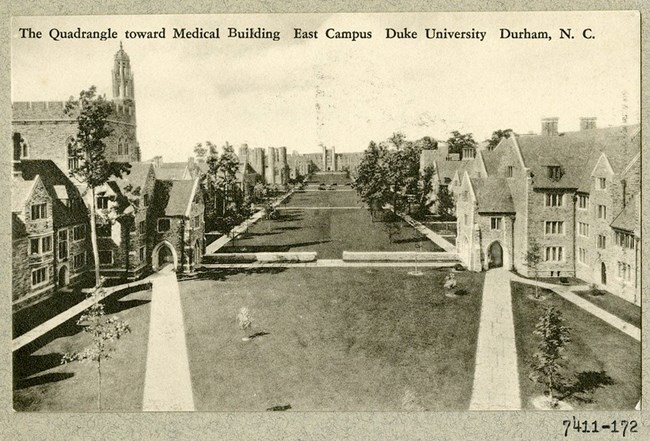

Olmsted Archives Duke University (Durham, NC)Once endowed in 1924, James B. Duke promised his university to be a beautiful, elite Southern campus to rival the colleges of the Northeast. While Duke had to whittle down a lengthy list of architects to one, Horace Trumbauer, there was only one landscape architecture firm he wanted designing his campus: Olmsted Brothers. Corresponding constantly with Trumbauer, Olmsted Brothers worked with the architect on the layout of buildings. Olmsted Brother’s plan was heavily influenced by Beaux Arts style design, with long vistas and strict axial designs. A part of their axial design would be Campus Drive, a forested thoroughfare serving as the spine of the campus, centering everything together. At Duke University, Olmsted Brothers were responsible for grading the land, establishing patterns of canopy trees, designing, and planting both quads, as well as the paths and roadways for the rest of the campus. Olmsted Brothers left Duke with a commitment to excellence in design and planning that still exists today, with the campus retaining a parklike setting of two thousand acres of open space along with six thousand acres of forest.

Olmsted Archives Bryn Mawr College (Bryn Mawr, PA)At the request of Bryn Mawr’s second president, Martha Carey Thomas, Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. made his first visit to the college in the spring of 1895. Olmsted’s one-time partner, Calvert Vaux, had developed the campus’ original plan 11 years earlier, but Thomas saw it as outdated, with populations and buildings growing in the years since. In association with the campus architects, Olmsted began working out a general plan for the campus. The focus of Olmsted’s plan would be to place buildings around the perimeter of the property, allowing for open space in the center intended for outdoor activities and attractive, unobstructed views. Olmsted’s ability to work closely with architects on the placement of larger buildings, such as the library, ensured his landscapes would compliment those structures. One of Olmsted’s final additions to the campus was a quarter mile oval bike path, lined with trees and looking in on that open recreational space. After Olmsted’s death, the firm would be inactive at Bryn Mawr until April of 1908, when Thomas again called on an Olmsted to help update an outdated plan. John Charles Olmsted would take over work at Bryn Mawr after his fathers’ death, and during his time working on the project, he received many letters from Thomas. While John Charles gets much of the credit for continuing the Olmsted work at Bryn Mawr, it was Martha Carey Thomas who was the driving force behind their involvement. In a letter to John Charles in November of 1908, she writes “of course we cannot afford to do much in any one year, but what we do ought to be done right”. Spoken like someone who has spent a good amount of time around the Olmsted’s. Thomas was involved in every detail of planning and execution for Bryn Mawr, a place she truly cared about and wanted to see succeeded. She even sketched a version of Olmsted’s 1897 plan that could be reproduced inexpensively, raising funds to complete the project.

Olmsted Archives Williams Colllege (Williamstown, MA)In 1902, Olmsted Brothers were asked to renovate areas of Williams College’s campus, including the President’s House and Cemetery. Though work on that initial design was completed in 1912, Williams chose to retain the advice of John Charles and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. Over the course of six decades, Olmsted Brothers would advise Williams through their gradual transformation with a campus design that was adaptable. Olmsted Brothers 1923 design for George A. Cluett’s estate was purchased by Williams College, adding to campus acreage. In the one hundred active years of the Olmsted firm, Williams College would be their largest commission in Western Massachusetts. From 1902 to 1962, Olmsted Brothers advised on Williams’s development, believing the campus should be planned around discrete quadrangles interwoven with shared green space. Present day grounds of Williams College reflect much of the original Olmsted Brothers design, with quadrangles and diagonal walks. Though their father taught them never to include a straight line in their designs, the exception was college campuses. While the rest of the adult population often need to be forced to take the longer path and meander for a little while, college students already know to do that.

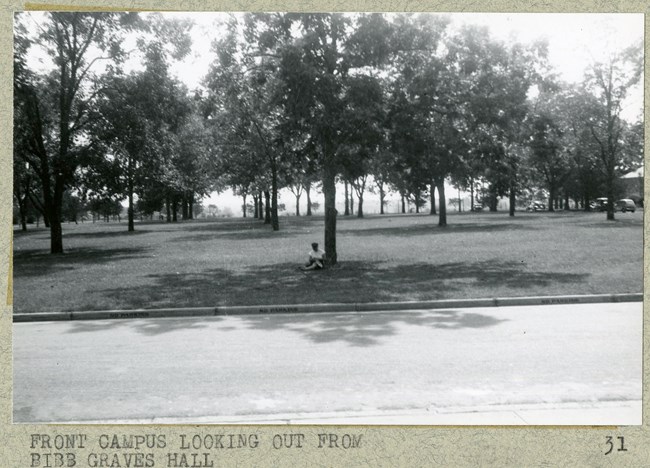

Olmsted Archives University of Alabama (Tuscaloosa, AL)In 1928, Olmsted Brothers were employed to perform a preliminary study for several of Alabama’s college campuses. That June, Alabama’s governor requested that an Olmsted representative visit each of the state’s colleges to estimate the cost of preparing a new campus plan. 36 total sites were visited, with the cost of the site visits totaling to $1,763.69.By 1928, John Charles Olmsted had been dead for eight years while Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. was nearing retirement, with 1934 being the year that Olmsted Jr. reduced his involvement in the firm to an advisory position. With Olmsted Firm members taking the lead, the Alabama College trustees did not approve their contract with the firm until October 1928. The Olmsted Firm provided landscaping plans and planting lists, as well as giving advice regarding the grading and engineering work of each property. Each Alabama institution would pay $1,500 for planning work, plus $1,500 to cover travel, assistants, drafting, and printing. Through their work together, Alabama’s Board of Education was required to consult the Olmsted Firm before allowing any alterations to be made to the finished plan.

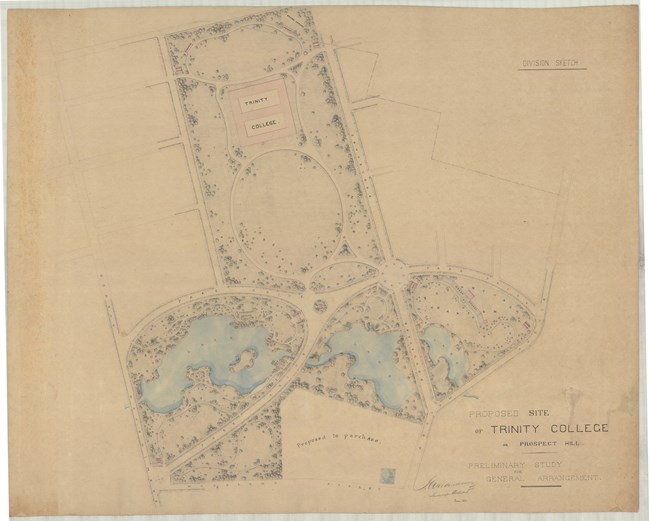

Olmsted Archives Trinity College (Hartford, CT)The passion Frederick Law Olmsted had for landscape architecture would make its way to his hometown of Hartford, Connecticut in 1872, when he worked with the city to relocate Trinity College to accommodate Hartford’s expansion. Trinity College’s Board of Trustees asked Olmsted to find the perfect plot of land and help design the college.Olmsted wrote to Trinity’s president, stating that a well- designed campus would foster the “acquisition of the general quality of culture which is the chief end of a liberal education.” The site for Trinity College was chosen according to criteria set forth by Olmsted, who also advised on the placements of buildings. Olmsted was involved in a massive expansion plan to add a chapel, dorms for students, lecture halls and recital rooms, a library, a museum of natural history, an observatory, an art gallery, a reading room, as well as homes for the President and professors. Olmsted and his sons would remain involved at Trinity up until the early 1890s, advising the planning and development of the campus for over twenty years.

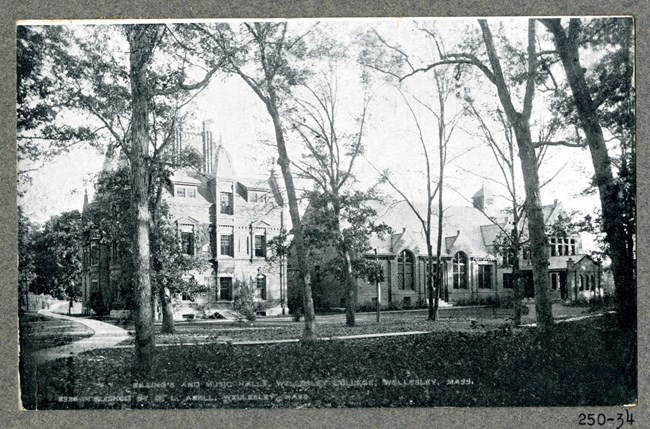

Olmsted Archives Wellesley College (Wellesley, MA)Frederick Law Olmsted Jr began his work at Wellesley College in 1902, providing a plan that accentuated the glacial topography of the area by grouping buildings on plateaus and edges, preserving the picturesque valleys. On his first visit to the campus, Olmsted Jr described the landscape as “not merely beautiful, but with a marked individual character not represented so far as I know on the ground of any other college in the country." He believed the glacial topography of the area gave the campus "its peculiar kind of intricate beauty."It wasn’t until the 1920s that Olmsted would be invited to develop the campus. With firm member Arthur Shurcliff, the firm completed a master plan that rejected the Beaux Arts quadrangle campus that was popular during the time. Olmsted Jr used his father’s design philosophy to preserve the site’s natural beauty. Olmsted Jr advised Wellesley to preserve its meadows, valleys, native plan communities and beautiful lake. Utilizing the natural configurations of the site, Olmsted Jr organized buildings into clusters, while framing the lake with quadrangles and courtyards. Meandering paths and boardwalks, lined with native and exotic vegetation, connected campus features while minimizing roads.

Olmsted Archives Phillips Exeter Academy (Exeter, NH)In 1781, husband and wife Elizabeth and John Phillips established an educational institution in their home of Exeter, New Hampshire. Years later, as the campus prepared to expand into the twentieth century, the Board of Trustees contacted Olmsted Brothers to assist in siting a new library, auditorium, dormitories, and to accommodate increased enrollment.Taking lead on Phillips Exeter Academy was John Charles Olmsted and associate Edward Whiting. In a thorough evaluation of the site, John Charles argued that certain properties must be acquired, regardless of cost, and that the elm trees already in Exeter should be preserved to provide an appropriate setting for the school’s library. While the first plan created was initial sketches for the location of the library, John Charles was determined to create an overall plan that would best serve the interests of the school. John Charles’ plan was met with mixed reactions, and work stalled. Olmsted Brothers continued to offer guidance at Phillips Exeter until 1952.

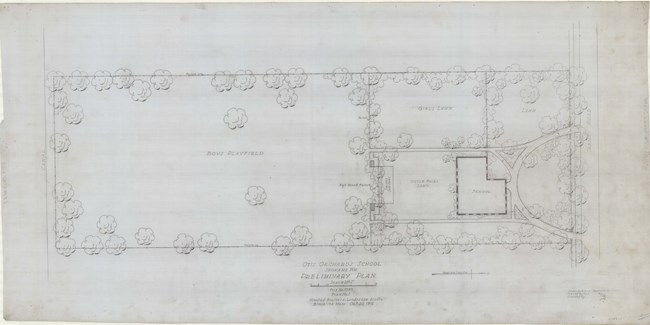

Olmsted Archives Otis Orchards School (Spokane, WA)In 1908, the Spokane Valley community of Otis Orchards built their “Cobblestone School” to replace their Territorial-era “Little White School on the Hill”. Designing the fieldstone school was Kirtland Cutter, who frequently collaborated with the Olmsted’s. Three years later in 1911, Olmsted Brothers drew up preliminary plans for the landscape of the school, creating separate play areas for boys, girls, and younger children.In Olmsted Brothers’ design for the school, they created a circular entry drive, lawns fenced in to protect the children, and trees planted along the perimeter. Unfortunately, the landscape crafted by Olmsted Brothers was lost in 1923 when the school burnt down, and a replacement was built on the site.

Olmsted Archives Troy Normal School (Troy, AL)Troy University got their Olmsted-designed landscape thanks to Edward M. Shackelford, a professor turned President of the growing University, who helped Troy in their greatest period of growth. While Shackelford got the Presidency in 1899, it wasn’t until 1922 that he reached out to Olmsted Brothers seeking guidance on the future of the school. Within days of Shackelford’s request, Olmsted Brothers responded expressing interest in working at Troy, estimating their cost between $1000 and $2000, however a lack of funding stopped Olmsted Brothers from beginning work in 1922.Thankfully, five years later, the Alabama State Legislature approved $5.4 million dollars for buildings throughout the State, and at the same time the Alabama Board of Education signed a deal with Olmsted Brothers to make plans for higher education institutions in the state. For several years, Olmsted Brothers studied and surveyed the landscape at Troy, eventually calling for a large, open pedestrian quad to anchor the campus. In a June 1930 letter, Olmsted Brothers wrote to Shackelford that Troy was “by far the largest of any of the schools” the firm was working on at the time. Olmsted Brothers worked with Troy for decades, with the Brookline firm sending a floral engineer to arrange plantings around the campus. When Shackelford saw the design, he called it “the finest piece of work of its kind that I ever saw.”

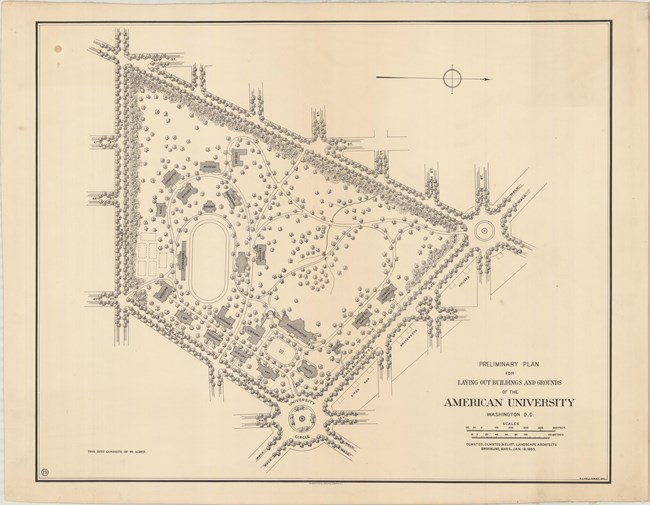

Olmsted Archives American University (Washington, D.C.)After working together on the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition, Frederick Law Olmsted and Henry Van Brunt partnered again for the design of Washington, D.C.’s American University. From 1891 to 1896, Olmsted and the architectural firm of Van Brunt & Howe transformed the former grounds of Fort Gaines into a 90-acre campus. A combination of financial constraints and subsequent development in the late twentieth century left much of Olmsted’s plans incomplete, however, some remnants remain.Olmsted and Van Brunt & Howe’s original L-shaped plan is still visible on the Main Campus, particularly in the Eric Friedman Quadrangle, a linear mall, with a religious house on one end and a library on the other.

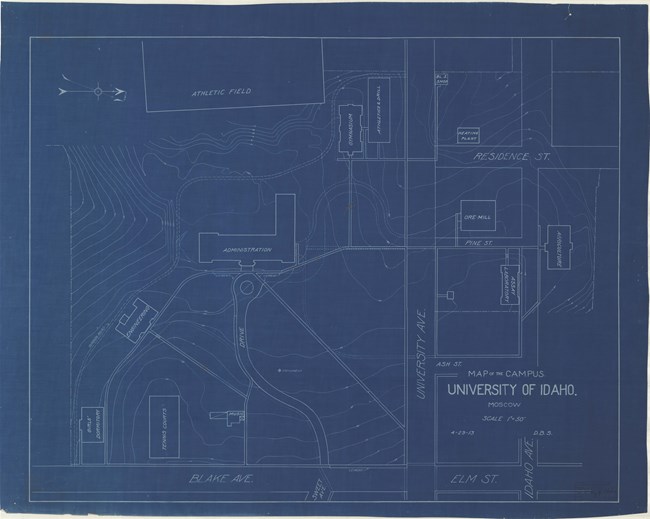

Olmsted Archives University of Idaho (Moscow, ID)In the Spring of 1907, Olmsted Brothers were invited to the University of Idaho by then President James McLean to provide a new plan for the growing campus. Visiting that summer, John Charles Olmsted created his report for the University in 1908, with sketches to accompany. John Charles called for the acquisition of land from the town of Moscow, including its railroad depot, so that roadways could be reconfigured to lead to campus.In a 1908 letter to McLean, John Charles wrote that “The university as a whole, both grounds and buildings, without a suggestion of lavishness or over decoration, ought to exhibit clearly, in all its outward appearance, the fact that it is the place of work and of residence of cultivated and careful people,”. To complement and frame academic buildings, John Charles recommended a conservative use of trees.

Olmsted Archives University of Louisville (Louisville, KY)In 1923, the University of Louisville was dealing with a rapid expansion, and to handle the new influx of students, the school began acquiring more property. To deal with the expansion, Olmsted Brothers were contacted by then University President Arthur Ford to inspect the site and create a plan. Olmsted Brothers sent firm member James Dawson down to Kentucky that year, though they would not formally begin working until two years later after the acquisition of a former children’s home and industrial school.In addition to James Dawson, Edward Whiting also guided work at the University of Louisville, adapting the grounds and recommending that drives and walks be rerouted to create a more cohesive campus. Whiting proposed a series of quadrangles to be anchored by the library, while local architects disagreed, suggesting an elaborate cross-shaped lawn. Whiting also suggested a single entry point for the University, which would diverge once inside the campus fence to discourage outside traffic from entering.

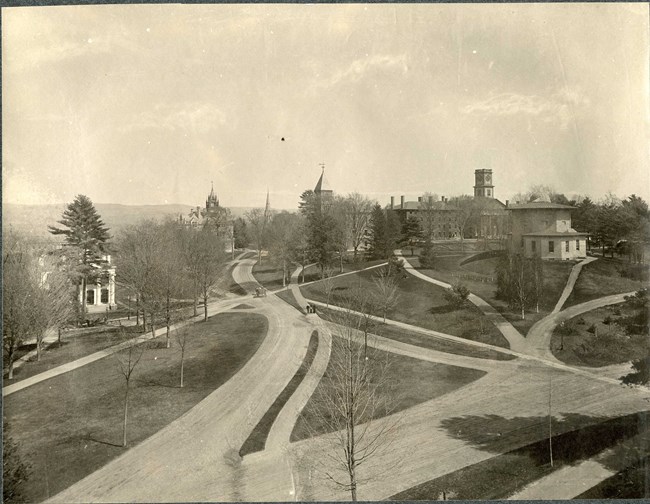

Olmsted Archives Amherst College (Amherst, MA)For fifty years, the Olmsted firm was involved in the improvement of Amherst College, starting with Frederick Law Olmsted Sr., and continuing to his sons John Charles and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. in 1870, Olmsted Sr. created the firm's first plans to improve the grounds, partnering with Calvert Vaux. To manage a growing campus population, Olmsted suggested school buildings be centered around a common green, like he had done in many towns and city designs and be connected via a circular path system.In the 1890s, with his father’s health beginning to fail, John Charles took over at Amherst, with the help of firm member Herbert Kellaway. During this time John Charles also collaborated with the architecture firm McKim, Mead, and White for the location of a new science building. By 1906 it was time for Olmsted Jr. to take over work at Amherst, with the college’s trustees creating the Commission for Improvements to Amherst College, with Olmsted Jr., McKim, Mead, Daniel Burnham and sculptor Augusts Saint-Gaudens all being appointed. That year the group submitted a report, making recommendations to acquire more land for the growing student population, while still following Olmsted Sr.’s original plan. In 1916, Amherst Trustees agreed to continue to honor Olmsted Sr. 's plan, with Olmsted Jr. and firm member Edward Whiting overseeing development until 1925. Today, Amherst College, at one thousand acres, retains much of Olmsted Sr.’s original design concept.

Olmsted Archives Hinckley School (Hinckley, ME)Work on the Hinckley School in Maine was first begun by Charles Rust Parker in 1914, when the school hired him for a campus extension. Parker began his career with Olmsted Brothers after graduating from Phillips Andover Academy in 1901. Parker stayed with Olmsted Brothers, learning everything he could until 1910, at which point he left Brookline to open his own practice in Portland, Maine.Wanting a home-like campus, Parker implemented a curvilinear road system, stone entrance gates, an artificial pond, and outdoor athletic fields. He also chose the location for new dorms, a dining hall, gymnasium, and the school’s administrative building. Parker also wove paths through woods and meadows, and spaced-out stone monuments across the campus, many of whom were leaders in the outdoor movement. During WWI, Parker closed his practice, choosing to lend his talents to the United States government. In 1919, he returned home to Maine, but this time as an employee for Olmsted Brothers. The Hinckley School reached out to Olmsted Brothers in 1926, and with his extensive knowledge of the site, Parker led the design, working until 1928.

Olmsted Archives University of Maine (Orono, ME)When President Lincoln signed the Morrill Land Grant College Act in 1862, Maine’s College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts became one of the nation’s first land grant colleges. Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux were called to design the campus in 1867, though their plan was initially rejected by the college’s trustees. The only section of Olmsted and Vaux’s plan that was adopted was the orienting of academic buildings towards nearby Stillwater River, and including an open parade ground and arboretum.The Olmsted name would have another chance in Orono, when Olmsted Brothers were hired in 1932 to address campus growth. Carl Rust Parker, who often took lead on Maine designs, called for a rectangular mall lined with elms and flanked by symmetrical, academic buildings. Parker also wanted to include a naturalistic lake and paths leading around the campus. Much of the original Olmsted design remains at the 600-acre campus. Olmsted Sr.’s original parade ground and arboretum are still intact, and Olmsted Brothers mall, though now lined with oak, is still present, and a major feature of the campus.

Olmsted Archives Princeton University (Princeton, NJ)In 1890, Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot were called to advise on the improvement of Princeton University, then called College of New Jersey. Creating a general plan for the campus, they focused on grading the land around existing buildings. In a letter to Moses Taylor Pyne, one of Princeton’s greatest benefactors and most influential trustees, John Charles Olmsted wrote that “The intention is to have long, graceful, easy slopes, nowhere steeper than would be practicable to walk upon, and leaving an ample breadth of nearly level ground all around the building, so that it will appear to have been placed upon a natural plateau.”

Olmsted Archives Rochester University (Rochester, NY)In 1923, Olmsted Brothers were hired by then Rochester University to help develop a new campus for a growing student population. Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. led the design team, with associates Edward Whiting and Faris Smith assisting. Their plan would develop the campus into an academic sanctuary, providing views of nearby Genesee River, and tying into the city’s strong horticultural tradition.The first section of the plan to be developed was the Eastman Quadrangle in 1927; an expansive lawn with symmetrical concrete paths cutting through, all framed by rows of oak and elm. While Olmsted Sr. was long gone when the development started, he had designed a nearby riverwalk, which Olmsted Jr. integrated into the campus grounds. Today, the 600-acre campus preserved as much of Olmsted Brothers design as possible.

Olmsted Archives West Point (West Point, NY)While most designs see a client or institution hiring landscape architects, in the case of West Point, architecture firm Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson chose Olmsted Brothers in 1902 to collaborate on the design and improvement of the existing grounds of the U.S. military campus. For ten years Olmsted Brothers worked at West Point, expanding the campus into newly acquired land.Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. took lead on this design, with assistance from Edward Clark Whiting. They felt that variety in trees and greenery should be introduced to the site. Olmsted Jr. felt this would “add interest and pleasure to places which are now rather monotonous or even disagreeable. My idea is that for this purpose much native shrubbery, to be collected in the reservation, should be used.” In addition to an extensive planting plan, Olmsted Brothers also drew plans for staff headquarters, Lieutenant’s quarters, a gymnasium, and several academic buildings. |

Last updated: June 18, 2024