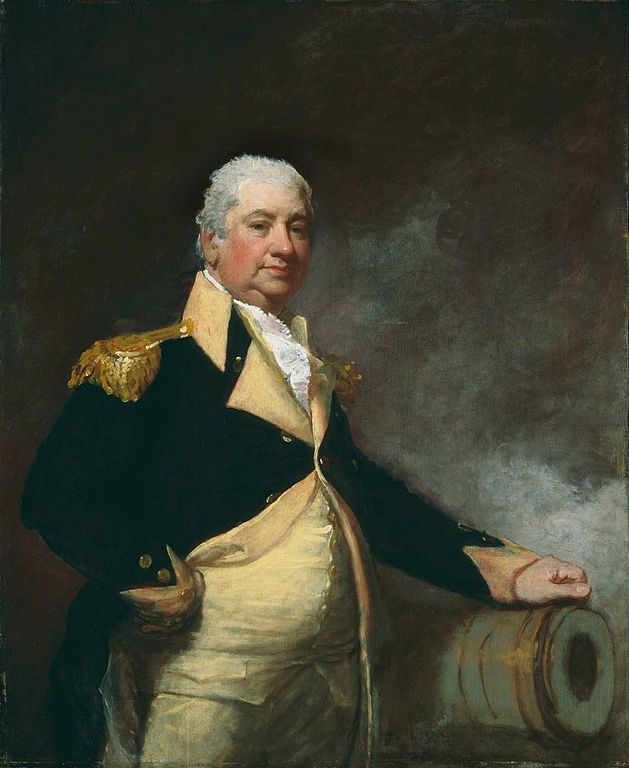

A Portrait of Henry Knox, by Gilbert Stuart, 1806

It was the middle of August 1783 and peace was at hand. While the fighting of the American Revolution had ceased, the British still occupied New York City and western outposts. But despite the peace, General Washington was annoyed. The General had just returned from a tour of upstate New York. He visited battlefields at Saratoga, Fort Ticonderoga, Crown Point and Fort Stanwix. When he returned to his quarters at Newburgh, he found his wife suffering from a fever. He also found a letter from the Continental Congress requesting his presence at its new temporary capital at Princeton, New Jersey. This would mean moving his military family, his sick wife and all their baggage to a new headquarters.

After allowing time for Martha’s recovery, Washington and his military family set off for Princeton on August 18th. Washington stopped at West Point for a few days to settle the affairs of the army and prepare for the occupation of the western outposts. Many officers thought it would be the last time they would see Washington.

Colonel Heman Swift who commanded the consolidated Connecticut regiment wrote to Washington’s aide David Humphreys on August 16th, “It is with the most affectionate Feelings of Respect we are informed the Commander in Chief is soon to leave the Army & uncertain whether he will return to this Post—as he has not publickly announced his Departure we are not at liberty formally to take our Leave of him—We cannot however in justice to our Feelings reconcile his Departure without giving him the liveliest Testimonials of our Sentiments & Esteem, & wish you to communicate them to him in such Manner as under the present Circumstances, is thought most proper…”

Between the sad sentimental officers and a grumpy Washington there was an unhappy tension in the air. As they walked through a West Point storehouse someone lightheartedly suggested that they all weigh themselves on a large scale normally used to weigh sacks of grain. Washington, looking to change his mood, agreed. As a result, we have the following figures.

“August 19, 1783

Weighted at the Scales at West Point.

Gen. Washington, 209 lbs.

Gen. Lincoln, 224

Gen. Knox, 280

Gen. Huntington, 132

Gen. Greaton, 166

Col. Swift, 219

Col. Michael Jackson, 252

Col. Henry Jackson, 238

Lieut. Col. Huntington, 232

Lieut. Col. Cobb, 186

Lieut. Col. Humphreys, 221”

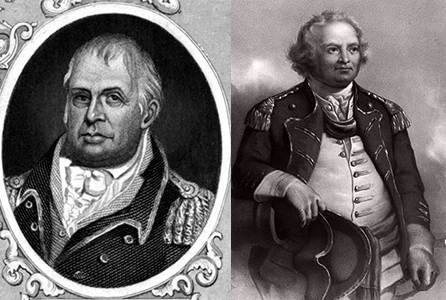

General Benjamin Lincoln, portrait by Henry Sargent, courtesy Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

General Benjamin Lincoln, portrait by Henry Sargent, courtesy Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.For those who were curious, General Lincoln was Benjamin Lincoln who was serving as the Secretary of War. General Henry Knox, who commanded the army’s artillery, had been appointed two days earlier to take over the command of all the troops at West Point during Washington’s absence. Jedediah Huntington was a brigadier general from Connecticut. While John Greaton from Massachusetts had recently been promoted to the rank of brigadier general. Colonel Heman Swift, who lamented Washington’s departure, commanded the Connecticut regiment. Colonels Michael and Henry Jackson both commanded Massachusetts regiments. Ebenezer Huntington was a lieutenant colonel who had served in the Light Infantry during the Virginia campaign of 1781. Finally, lieutenant colonels David Cobb and David Humphreys both served as aides-de-camp to General Washington.

The fever that Martha had contracted in Newburgh had spread through Washington’s servants and aides. In New Jersey on September 23rd, Washington wrote to General Knox, “…Humphreys & Walker have each had an ill turn since they came to this place—the latter is getting about, but the other [Humphreys] is still in his Bed of a fever that did not till yesterday quit him for 14 or 15 days.” He also joked about Humphrey’s weight revealed by the West Point scales, “The danger I hope is now past, and he has only his flesh to recover, part of which, or in other words of the weight he brought with him from the Scales at West point…”

While the weights eleven officers might seem trivial, it’s really a rare bit of historical information. Scales were not a common item in 18th century homes. The weights of people were rarely recorded. Though I did find one other instance of an officer weighing himself. This account comes from the diary of Lieutenant Jabez Fitch a prisoner of war on Long Island, “…I went down to the Grist Mill & observing a pare [pair] of large Scales, desire’d Mr. Crane to weigh me, which he did, & found my Wt. 203 lb….”

In most cases eighteenth century people really didn’t care about someone’s exact weight. At this point the modern phenomenon of “body shaming” wasn’t in vogue. Baroque paintings of this period, by artists like Rubens, usually feature plus-sized women and stout men. People with a bit of weight were considered prosperous because they could afford extra food and didn’t burn off the weight by hard exercise. Fat, within reason, was fashionable. But fat in excess was not favored.

The average 18th century American man was about five feet, nine inches tall. The average weight of an men of that height varies between 129 to 183 pounds. Except for Washington, I don’t know the heights of our eleven officers. But only three men [Jedediah Huntington, John Greaton and David Cobb] fell within the “average weight” range. The other eight were heavier than average. General Knox at 280 pounds was the heaviest.

But was Henry Knox the biggest man in the Continental Army? While we have few other recorded weights, we do have some descriptions of some of the huskier officers in the Continental Army. Marquis De Chatellux described General Knox, at 280 pounds, this way, “General Knox… is a man of thirty-five, very fat, but very active, and of a gay and amiable character.”

While Claude Victor de Broglie said that “Mr. Lincoln, the Secretary of War is also quite corpulent.” Weighed at West Point, Lincoln was 224 pounds. And Chatellux described General Heath as “His countenance is noble and open; and his bald head, as well as his corpulence, give him a striking resemblance to Lord Granby.” Doctor James Thacher thought that General Putnam was “In his person he is corpulent and clumsy, but carries a bold, undaunted front.”

Despite all these corpulent officers, veteran Christian Shank in his pension application stated that his former colonel, “Emphraim Martin, …was said to be the stoutest man in the army” But without an actual weight, the title is uncertain.

However, if there was a prize for the heaviest man in the Continental Army it probably would go to Colonel Israel Shreve of the New Jersey Brigade. Shreve’s own son in a pension application described his father Israel as “a very fleshy man” and “a very corpulent man.” In a published recollection of his father John backed up his claim with the facts stating, “My father being very fleshy, weighing three hundred and twenty pounds, left the service on half pay…”

While not the winners, Lincoln and Knox were stout men. Based on the known weights, General Knox at 280 pounds takes second place.

Portraits of General William E. Heath and General Israel Putnam

Special thanks to "Uncle" Eric and Morristown National Historical Park for this overflowing entry! And in case you were curious...British Brigadier General Lawrence Nilson [below] shows that British officers could be corpulent too!

SOURCES

- Painting - Henry Knox - Wikipedia

- From Heman Swift to David Humphreys, 16 August 1783, National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-11697

- The Central Gazette, Charlottesville, Virginia, September 29, 1820

- Painting - Benjamin Lincoln Papers | National Archives

- Who Was Who in the American Revolution, by L. Edward Purcell, Facts on File , New York, c.1993

- From George Washington to Henry Knox, 23 September 1783, National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-11847

- Lt. Jabez Fitch, 17th Connecticut Regiment, The New York Diary of Lieutenant Jabez Fitch edited by W.H. W. Sabine, 1954, pg. 235

- getcalc.com/health-ideal-weight-calculator.htm?gender=male&height=5ft9in

- Marquis De Chatellux, Travels in North America in the Years 1780, 1781 and 1782, by Marquis De Chastellux, translated by Howard C. Rice, Vol. 1, 1963, pg. 112

- Claude Victor de Broglie, Narrative of the Prince De Broglie 1782, Translated from the Original MS by E. W. Balch

- The Magazine of American History, Vol. I, A.S. Barnes & Co. New York & Chicago, 1877, pg. 307-309

- Marquis De Chatellux, Travels in North America in the Years 1780, 1781 and 1782, by Marquis De Chastellux, translated by Howard C. Rice, Vol. 1, 1963, pg. 92 - 93

- James Thacher, Military Journal of the American Revolution…pg. 147-148

- Israel Putnam portrait - Israel Putnam - Wikipedia

- Engraving - William Heath - Wikipedia

- Pension application of Christian Shank, W 19344

- John Shreve Pension application S 3890, November 12, 1828, and August 28, 1832

- Personal Narrative of the Services of Lieutenant John Shreve, The Magazine of American History, Volume III, 1879

- Painting - Benjamin Lincoln - Wikipedia

- Painting of General Knox – National Park Service

- Painting British Brigadier General Lawrence Nilson by George Romney in The power paunch: body politics and eighteenth-century men's waistlines, Posted 12 Apr 2021, by Jon Sleigh

- Portrait of Alderman Richard Barham, The power paunch: body politics and eighteenth-century men's waistlines, Posted 12 Apr 2021, by Jon Sleigh