Above: An example of the stamps required by the British Parliament to be affixed to colonial legal and commercial documents.

Among early historians researching New York during the American Revolution, the lack of numerous large scale public radical acts against British authority helped forge the reputation of it having been a largely Loyalist colony. If one looks closer however, this reputation is undeserved. It was in fact a very radical public act that brought about a change in how pre-war opposition to England would be handled by “rebel” leaders in New York.

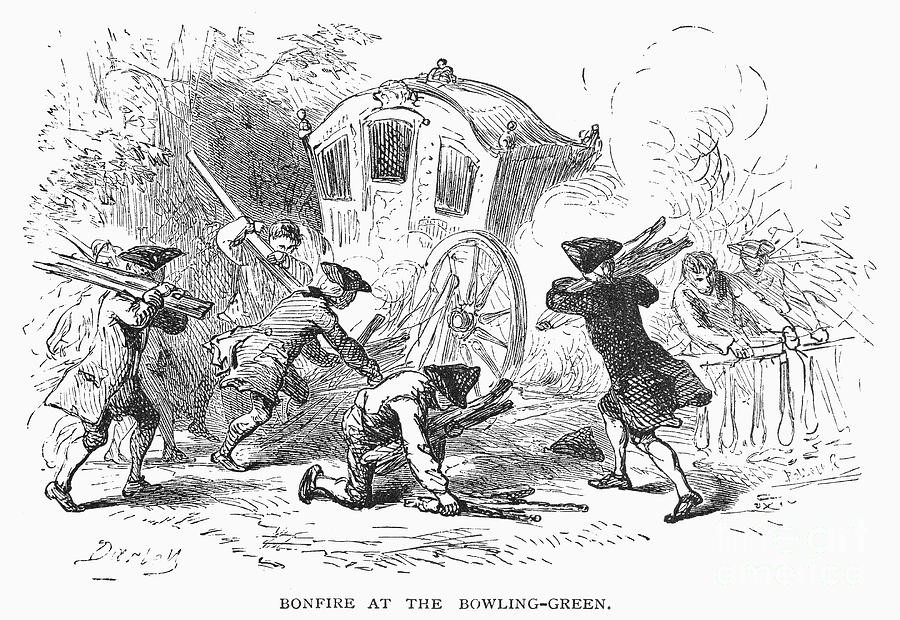

The Stamp Act was passed on March 22, 1765. This was the first attempt by parliament to place an internal tax on the colonies. It required an official government stamp (which had to be purchased) to be affixed to all colonial commercial and legal papers, including newspapers, playing cards and almanacs. When the ships bearing the stamps arrived in New York City on Oct. 23rd, around 2000 residents gathered at the harbor to protest. On the evening of October 31 (the stamps were to go into effect the next day), a mob of another 2000 coordinated by the city’s “Sons of Liberty” group threatened to storm Fort George where the stamps were secured. The mob tried to goad the soldiers into firing at them, and bloodshed was only narrowly averted. Lieutenant Governor Cadwallader Colden’s coach and several of his sleighs were burned in sight of the fort and the house of the fort’s commander, Royal Artillery Major Thomas James, was ransacked and all his possessions burned.

Above: The burning of Governor Colden’s carriage during the Stamp Act Riots in New York City

A later attempt to storm the fort was narrowly stopped by more moderate leaders, but further rioting and vandalism occurred. When a second ship arrived in January 1766 with additional stamps, it was boarded, and the stamps removed and burned. This sort of “mob rule” and violence continued until news of the repeal of the Stamp Act reached New York City in May of 1766.

Even city and colony leaders in favor of resistance against the British government were appalled by the anarchy caused by the “Sons of Liberty” and their supporters. They resolved to limit the ability of a mob to control large scale resistance against the crown in the future. For the rest of the years leading up to the war, most resistance would be overseen by moderate leaders who favored economic and political measures to voice their displeasure to the British Parliament.

One example of this was New York City’s response to the Quartering Act. Also passed in 1765, it required the colonies to provide quarters, food and necessities to the British troops quartered there. Choosing passive resistance as their weapon, the New York Provincial Legislature simply ignored the measure. Parliament finally passed the “New York Restraining Act” in 1767. This allowed the Royal Governor of New York to dissolve the sitting assembly and reform new assemblies more open to parliament’s wishes. This occurred in both 1767 and 1769. It would not be until 1771 that the New York assembly finally passed any sort of funding for the lodging of British troops.

The mob could not be contained in every case however, particularly in New York City where friction between inhabitants and soldiers quartered there increased with each passing year. Part of what fueled this friction was the Liberty Pole that sat in view of the soldier’s barracks. Far from being a “loyalist colony,” the first documented raising of a Liberty Pole in the colonies was in New York City in 1766. Since that time, city inhabitants and British soldier had sparred over the pole, with new poles going up whenever the soldier were successful in cutting them down.

Above: A period cartoon of New York City’s Liberty Pole.

In January of 1770, the latest version of this fracas led to “The Battle of Golden Hill” (so called because it started near a large field covered with yellow flowers) on January 19th. This running brawl started when two “Sons of Liberty” accosted soldiers putting up broadsides attacking the “Sons.” The soldiers were eventually ordered back to their barracks, but rumors that the soldiers had drawn their swords led to many civilians following the soldiers to intimidate them. The two soldiers were eventually reinforced by several their comrades, tempers flared, and fighting began. Many soldiers and civilians were badly cut and bruised before all the soldiers were finally forced back to their barracks by their officers. Additional scuffles continued over the next few days. The transfer of most of the troops to Pensacola in May finally helped reduce further friction.

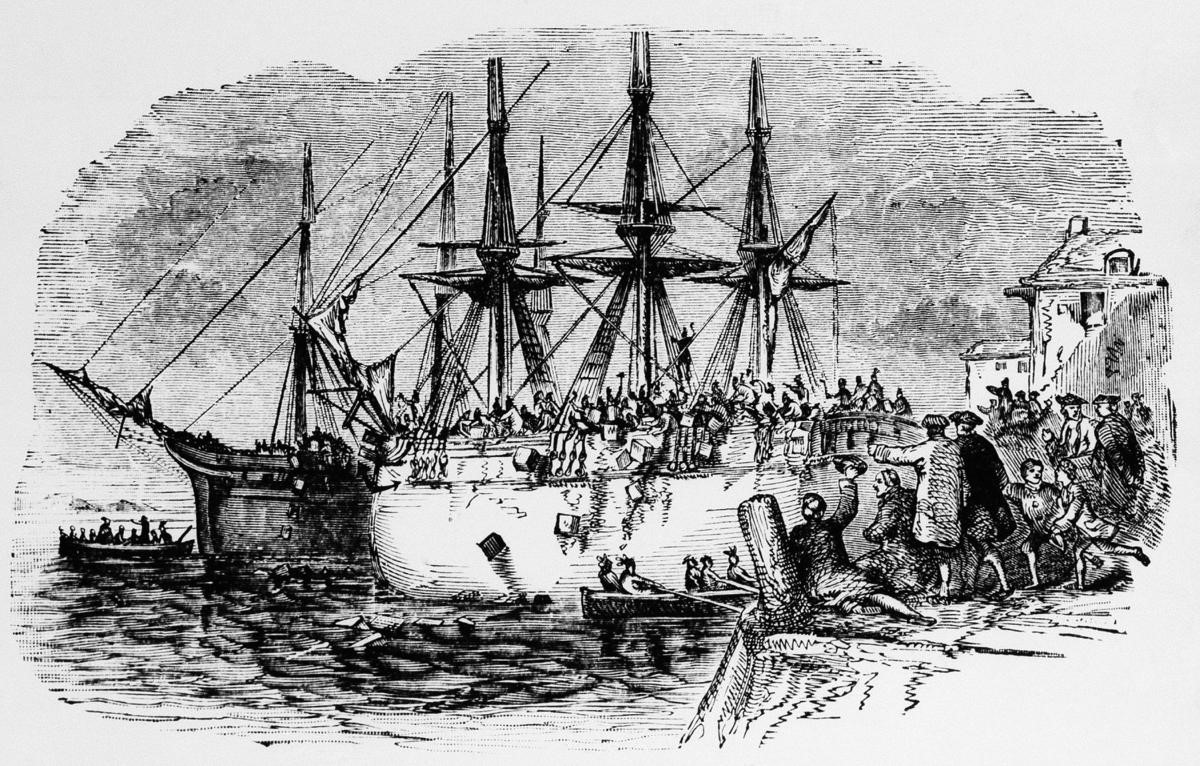

When news reached the colonies in 1773 that the East India Company would be allowed a monopoly to sell their tea in America, New York resolved to not allow the tea to land. It was in fact New York’s early public stand against the tea that finally provided Massachusetts radical Samuel Adams with the support he needed to shame Boston’s populace into not accepting the tea either. This led to the famous “Boston Tea Party” in December of 1773. Storms had delayed the tea ship bound for New York City, and it did not arrive until April of 1774. True to their word, New Yorkers finally forced the ship to return to England with the tea. In a mini version of the more famous “Boston Tea Party,” New York City residents boarded another ship holding a private stock of the East India Tea and dumped all 18 chests into the city harbor.

Unfortunately, many of the more radical colonies viewed New Yorks largely moderate approach of resistance as a betrayal of the colony’s commitment to maintain colonial unity in defying parliament’s measures. This laid the groundwork of mistaken notions that led early historians to brand New York as a mostly loyalist colony. If more researchers had come across this excerpt of a letter written by an English visitor with ties to the southern royal governments, they would have learned what royal authorities thought about supposedly “loyal New York”: “The inhabitants of New York have hitherto discovered sentiment favorable to government; but if the sword is unsheathed,…they will almost unanimously fall into the ranks of opposition.” – William Eddis, a young Englishman in the southern colonies, 1775.

Above: One of the many depictions of “Tea Parties” that took place in several of the colonies.

Sources:

Books

Ketchum, Richard M. Divided Loyalties: How the American Revolution Came to New York, New York: Owl Books, Henry Holt and Company LLC, 2002.

Ranlet Philip. The New York Loyalists, Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1986.

Internet

Carriel, Jonathan. The Grand Affray at Golden Hill: New York City, January 19, 1770, Journal of the American Revolution, February 25, 2020, March, 2020.