Research Report

Mississippi's Historic Schools Survey

by Jennifer V. Opager Baughn

Schools are, and have historically been, at the center of their communities. Thus, an understanding of the history of school buildings must include insights into how events have shaped schools and how schools have shaped events. National movements such as Progressivism, the New Deal, and the fight for desegregation touched even the most rural counties through the schools. School buildings—through their construction, occupation, and abandonment—illustrate the rise and fall of populations, and the movement of people to the cities and towns and of African Americans to the North. Schools also demonstrate the increasing standardization of the building trades and the growing professionalism of architectural practice. The importance of these and other themes provides a solid basis for convincing school officials and the public of the significance of school buildings and of the need to preserve them.

In June 1999, the Mississippi Department of Archives and History initiated a survey of all public schools in the state built before 1960. This survey included all buildings constructed as schools, regardless of their current use. Fieldwork has been conducted in each of the state's 82 counties and should be completed by August 2005. Early results indicate that at least 800 extant schools will be documented, and information about another 3,000 non-extant resources will be added to Mississippi's Historic Resources Inventory.(Figure 1)

The historic schools survey assists Archives and History in its function as the State Historic Preservation Office for Mississippi, primarily in its task of collecting information about historic resources around the state and using that information to carry out Section 106 reviews.(1) In addition to its federal mandate, under Mississippi's Antiquities Law of 1970, Archives and History is responsible for protecting publicly owned historic properties by designating such buildings as Mississippi Landmarks and reviewing any changes to landmarks or buildings deemed eligible for landmark status. Since public schools are the most common publicly owned buildings in the state, Archives and History has been interested for some time in obtaining a better understanding of school buildings and their historic contexts in order to better evaluate the structures under the Antiquities Law. Until this survey, documentation of historic schools was not systematic. Moreover, Archives and History did not have a framework other than architectural style within which to consider buildings already documented in the Historic Resources Inventory. Emphasis on architectural design meant that the vast majority of historic school buildings in the state were ignored because they were vernacular in character rather than impressive stylistic statements.

Although the school survey grew out of admittedly bureaucratic priorities, the extensive research and travel needed to conduct the survey has broadened our staff's awareness of Mississippi resources and has forced us to focus on subjects larger than individual school buildings, such as the history of education and segregation, and national movements that brought sweeping changes to our built environment.

Fieldwork for the historic schools survey is organized around a valuable group of records created by the Mississippi Department of Education in the 1950s. At the center of these records is a statewide survey of public schools carried out by the Department of Education from 1953 to 1956 at the behest of the Mississippi legislature. This three-year survey was the beginning of Mississippi's attempt to bolster the state's system of racially segregated schools—which were, up to that time, separate but by no means equal—by bringing facilities for black and white children to the same standard. As part of this equalization effort, each of the state's 82 counties was required to survey its school buildings. The surveyors took photographs of each structure and documented condition, number of classrooms, date of construction, and other data. The result was a vast body of material about public schools at that time, including many that were abandoned by the end of the 1950s. Because so many small, unconsolidated schools for African Americans existed during the 1950s survey, the majority of the photographs document black schools—schools about which we previously had no knowledge because most have been lost through demolition or decay.

The photographs and reports of this 1950s survey eventually made their way to the state archives—a division of Archives and History and the official repository for public records deemed of importance to posterity. After an archivist brought this record group to our attention, we became more aware that the official archival records collected by different state agencies for their own purposes might be of similar use to Archives and History in building its Historic Resources Inventory.

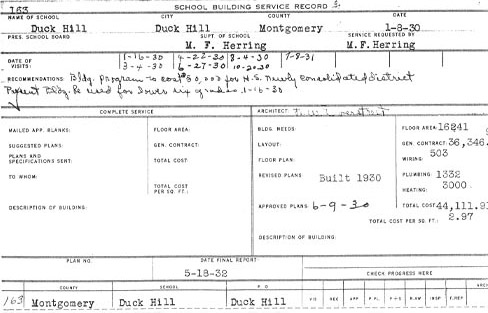

In addition to the 1950s school survey, the Department of Education record group also includes a card file called School Building Service Record Cards. These cards recorded standardized designs that were sent to school officials throughout the state by the School Building Service—founded in 1929 as a division of the Department of Education—and the dates of meetings between department staff and architects for each school construction project. Archives and History's research and fieldwork has uncovered much useful information about the School Building Service and its large collection of standardized building plans that were sent to school superintendents or principals upon request. Designs included schools ranging in size from 1 classroom to at least 12 classrooms, as well as vocational buildings, home economics cottages, gymnasiums, cafeterias, and teachers' houses. Unfortunately, the Department of Education apparently did not retain full sets of the designs, but recent research uncovered a number of the drawings in State Building Commission files in the state archives. Archives and History has also determined the characteristics of various standard types, previously known only by their Department of Education sequence numbers, through fieldwork on extant examples. Much work remains on this front, however, and we hope to find a complete set of drawings in the future. (Figure 2)

Another source of invaluable documentary material has come from the Julius Rosenwald Fund collection at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. The Rosenwald Fund contributed money and designs for African American schools throughout the South from the 1910s through the early 1930s, and its records include photographs of many of the schools that it helped to finance. Mississippi was second nationally in the number of schools built with Rosenwald support. Over 600 school buildings, vocational buildings, and teachers' homes were built, making the 1920s a time of great progress in African-American education in the state—a time about which Archives and History had very little information before the historic schools survey.(Figure 3)

Material from all of these sources combined to provide Archives and History with an organizing framework for our modern-day survey. Considering the rapid increase in demolition and abandonment of public schools in Mississippi during the 1990s, our first concern has been to conduct fieldwork concurrent with documentary research, since the tangible resources are disappearing from the landscape. Indeed, a number of buildings has been torn down in the few years since they were surveyed. The decision to begin fieldwork almost immediately after starting our research was the right one, but it did result in some gaps in the early stages of the survey. For instance, in the first two summers of the survey, Archives and History staff did not document any buildings built between 1955 and 1960 because the buildings did not appear in the 1953-1956 Equalization survey. However, after discovering the School Building Service Record Cards and realizing that a massive school building program had reshaped the educational landscape in the late 1950s, we began to document these later buildings. An understanding of their importance came from documentary research rather than fieldwork, and now we will have to return to the counties to document buildings that we overlooked in the early stages of fieldwork.

Our fieldwork methodology represents the culmination of a large amount of copying, sorting, and mapping. Copying the survey material from the archives, organizing all of the material by school, and mapping the location of each school is a time-consuming process, but one that must be completed to the most tedious detail to ensure a useful day of fieldwork. Mapping is an especially crucial component. Old maps from the 15-minute USGS topographic series were particularly helpful, as most 15-minute maps for Mississippi date to the 1940s and 1950s and show the locations of the schools before the Equalization period. For counties that were not covered by this series, further archival research produced a set of old county highway maps on which Department of Education staff had marked the locations of each school documented in the 1953-1956 survey. While geographic information on county highway maps is not as detailed as that on the USGS maps, the highway maps provided at least rough school locations that could be investigated in the field.

After compiling this information for each county, Archives and History staff conducted fieldwork in the summer months, visiting the location of each school for which we had geographic data. Findings indicate that most of the African American schools and many of the white schools are abandoned or gone, their students having been consolidated into fewer centrally located schools.

After refining our research preparations and field procedures, we completed surveys in 20 counties each summer from 2001 to 2003. The resulting documentation includes detailed photography of the exteriors and interiors (when accessible) of about 800 school buildings and/or complexes; notes on architectural details such as door types, windows, and transoms; and floor and site plans noting classrooms, auditoriums, offices, later additions, and other significant features of the building or complex.(2)

Although not yet complete, the Mississippi Department of Archives and History's historic schools survey has opened new doors for preserving these important historic resources. In 2001, the state legislature approved a grant program to provide funding to preserve historic courthouses and schools in Mississippi. The grant program is now in its third round. Information gathered from the historic schools survey has been invaluable in administering these grants, as well as in other, more routine reviews. In addition, Archives and History now has an increased understanding of an important part of our state's history and architectural legacy. It is our hope that the survey will continue to aid us in our mission to preserve Mississippi's historic resources in the coming years.

About the Author

Jennifer V. Opager Baughn is an architectural historian with the Historic Preservation Division, Mississippi Department of Archives and History. She can be reached at jbaughn@mdah.state.ms.us.

Notes

1. Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act requires federal agencies to identify and assess the effects of its activities on historic resources.

2. A complex includes the main administration building and secondary buildings, such as gymnasium, vocational building, and teachers' homes.