Article

America's World War II Home Front Heritage

by Roger E. Kelly

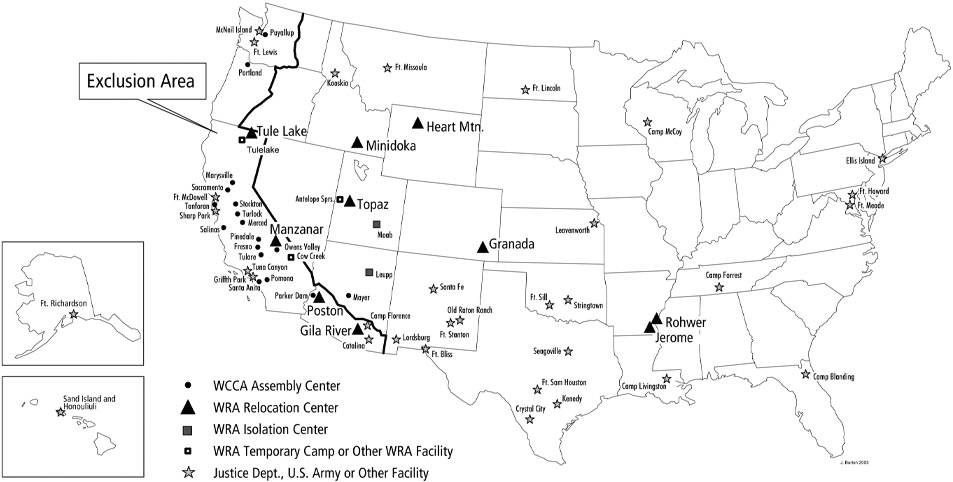

Evidence of our World War II home front can be found beneath farm fields, on grazing parcels or public lands, within former and active military installations, or in rural forests. Structures, buildings, and objects connect the global war of 1941-1945 to participants and their descendants. In 1991, the nation commemorated the 50th anniversary of the United States' entry into World War II. The nation is now approaching the 60th anniversary of the Allies and the United States Victory over Japan and Victory in Europe, celebrating the war's end. This article aims to enhance our understanding of our nation's history and the physical heritage of our wartime-era home front.(Figure 1)

Much has been written and spoken about how the United States participated in, and was changed by, the world conflict.(1) The nation's home front was like a goldsmith's crucible, recasting relationships between the country's majority and minority peoples into new images and unexpected forms. The nation used demographic diversity for dual, conflicting purposes—for wartime unity at home or "at the front," and for racial and ethnic separation of society, sometimes behind barbed wire. The places described here were crucibles where citizens began to form new images of American diversity.

Physical evidence of home front mobilization, the confinement of certain groups, military defense, or war matériel production speak volumes about wartime political and cultural behavior. Even though these material remains are only several decades old, they are finite heritage resources with relevance across today's living generations just as Civil War battlefields resonated across earlier (and present) American generations. But unlike widely held personal memories of hardships, victory gardens, ration coupon books, and the loss of family members, tangible evidence is unevenly scattered across the United States. Coastal states with fortified cities and shipyards, forested mountain regions, and rural agricultural lands witnessed different home front landscape uses than midcontinent manufacturing centers and Sun Belt states.

If recognized and preserved, tangible World War II home front heritage can contribute to social and political histories, develop deeper feelings of patriotism and reflective nostalgia, encourage cross-generational communication, and inspire grassroots heritage tourism for today's citizens. Varieties of home front heritage—landscapes, objects, structures, memories, stories, and secrets—are diminishing as are the number of the people directly associated with this past.

Specific examples discussed here were chosen utilizing five criteria: 1) historic involvement of large groups; 2) pertinent, accessible, and reliable information; 3) extant associated archeological, architectural, historical, and other materials; 4) active local preservation or museum presentations focused on home front themes; and 5) interest groups of original participants, their descendents, and friends. Information sources are published works, news articles, websites, personal observation, and persons identified in acknowledgements. Other wartime historic venues and properties such as the Trinity Site, sunken warships at Pearl Harbor, laboratories at Oak Ridge or Berkeley, and historic ships are very important, but are not included here. Heroic military units have significant stories that are commemorated elsewhere.

We can learn from other nations with similar home front histories. Researchers in the United Kingdom, for example, have inventoried extant World War II-era facilities in the English countryside and produced studies showing impacts of prisoner-of-war labor on agricultural production. As part of its mission, Britain's English Heritage organization promotes national stewardship of military heritage through site sustainability, "beneficial reuse," documentation before land development, and encouragement of community support. Near Malton in North Yorkshire, a preserved prisoner-of-war camp containing 30 barracks, each with displays of European and Great Britain wartime topics, was developed as a World War II historical park.(2)

Identifying World War II Home Front Places

Some American home front locations are identified by visible foundations or vacant structures, towering smoke stacks, abandoned roadways, still-occupied buildings, relocated barracks, fortifications, abandoned shipyard facilities, or supply depot elements such as munitions bunkers.(3) Many extant World War II structures, buildings, and features have been identified during cultural resource inventories for active military installations, some federal and state parks, and local jurisdictions. But many locations contain little or no evidence of significant wartime activities due to substantial changes in land use.

Archeology, history, and historic architecture are effective partners for detailed documentation and preservation of civilian and military architecture, particularly remnants of now-gone structures. Archeological investigative techniques, such as research designs, test excavations, mapping, and artifact studies are applicable when above-grade fabric is missing. Archeological methods can also be useful for tracing buried infrastructure systems, recording historic graffiti and abandoned objects, and comparing as-built conditions and original designs.

Industrial archeology is a cross-disciplinary professional field, blending architecture, historical technology, and archeology that can be useful in documenting World War II-era sites. The Army Engineer Museum at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, includes exhibits and archives of wartime temporary buildings used nationwide from 1939 to 1945. Examples of home front historic architecture assessment reports include the Old Hospital Complex, the Waste Water Treatment Plant and Incinerator Complex at Fort Carson, Colorado; the Presidio of San Francisco, California; and the Old Parade Ground and MacArthur Avenue at Fort Mason in San Francisco, California.(4)

Major Types of World War II Home Front Properties

Four broad categories of historic places provide a framework to discuss tangible evidence of the nation's 1941-1945 home front. The first category, "controlled group camps," includes centers and camps for interned Japanese Americans; facilities for military prisoners; "Civilian Public Service" quarters for conscientious objectors; "enemy alien" facilities for Axis diplomats and other civilians believed to be a threat to the nation; and facilities for the Aleut Alaska Natives removed from their island villages. The second category includes military-related facilities, permanent or temporary, for defense, training, logistical operations, armament storage and transport, and battlefields. The third category encompasses industrial facilities such as contract and government shipyards, airplane assembly plants, and munitions deployment centers. The final category includes civilian facilities such as defense-worker housing. Examples from each category will be used to illustrate the opportunity for enhanced heritage awareness. The categories are not equal in terms of coherent, accessible information. The first and second categories have much larger bodies of usable literature and extant examples, thus producing a regrettable imbalance in this essay.

Some home front places are designated as National Historic Landmarks, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, or appear in state registers. Often designations are based primarily on historical research. Archeological significance may not be identified. Perhaps assumptions are made that little tangible evidence of wartime activity remains embedded on or in a specific property. For some places, remodeling and land reuse have impacted a wartime landscape, but some buried or obscured features may be extant as significant and valuable reminders.

Because a recent overview of the wartime evidence in Hawaii and the Pacific is available, this essay is focused only on America's continental and Alaskan home front.(5) Public interest in wartime history and places has increased for many reasons, including Tom Brokaw's "greatest generation" best sellers, European battlefield tourism, and recent Hollywood films. Another encouraging example of interest is reflected in TRACES, a nonprofit grassroots consortium of amateur and professional historians, educators, and individuals who participated in home front life and hold an annual conference at Coe College in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. At least three guidebooks to historic home front military and civilian facilities are available. In 2000, the National D-Day Museum in New Orleans joined the growing number of museums illustrating World War II's significance to the nation.(6)

Controlled Group Camps

The early 1940s witnessed the unprecedented detention of an estimated 650,000 persons. "Impounded people," as described by anthropologist Edward Spicer, included Japanese Americans; Axis war prisoners; citizens of Italy, Germany, and Japan; Americans with "suspicious" surnames; Japanese living in Latin America; registered conscientious objectors; and Aleut Alaska Native people. Extensive literature exists on the experiences of these groups, the legal and moral issues of detention, and the operation of detention facilities.(7) Video documentaries of camps for Japanese Americans and Axis prisoners of war, and the restrictions placed upon Italian Americans are also available.(8)

Several federal agencies established facilities to hold detained groups in town-like camps, with basic housing, health services, subsistence supplies, recreation, and internal governance. Physical control of camp inhabitants ranged from maximum security at some prisoner-of-war camps to minimum confinement of civilian aliens. New camps were quickly built from military plans with basic one-story frame barracks, latrines, laundries, communal showers, warehouses, mess halls and kitchens, staff housing, and medical facilities, arranged in grid layouts with open firebreaks and bounded by wire fences and guard towers. In some locations, vacant Depression-era facilities or state prison facilities were re-used. Published recollections and oral histories of detainees within each type of camp give many details about daily life. These sources reveal how ethnic cultural expressions, such as decorative gardens and outdoor art, team sports, fitness clubs, religious practices, political opinions, written language expressed in camp newspapers or graffiti, diet, performing arts, and handicrafts, were adapted to confinement.

The persistence of ethnic culture by detained people can be documented in archeological, historic architecture, and landscape features. Equally important are perspectives about the interaction of surrounding communities with camp residents and among multinational camp populations.

Japanese-American Internment Camps

An inventory of the physical remains of Japanese-American camps and other detention facilities notes that in many locations, substantial structures such as smokestacks, root cellars, infrastructure features, cemeteries, roadways, and support buildings exist today.(9)(Figure 1) In addition, Japanese-style gardens and memorials, hidden graffiti in English and Japanese, and modern commemorative markers are present in many locations.

Perhaps the best-documented Japanese-American internment camp is Manzanar, the first to open in early 1942 and now part of the National Park System. Extensive archeological, historical, oral history, cultural landscape, and historic architecture studies have been completed, including an inventory of extant prehistory and prewar homestead evidence, and the documentation of the camp's physical features.(10) These studies supported planning the 540-acre national park. Planning participants included Japanese-American landscape architects, the Manzanar Pilgrimage group, a local museum, and neighbors. (Figure 2) As a result, the Manzanar High School auditorium has been restored as an interpretive center and a mess hall building was recently relocated to its original position. The Manzanar National Historic Site Interpretive Center opened April 24, 2004, in conjunction with the 35th annual Manzanar Pilgrimage.

|

Figure 2. During a ceremony at the camp cemetery, participants of the 2003 Manzanar Pilgrimage gathered at the I Rei To or "soul cleansing tower." (Courtesy of the National Park Service.) |

The other nine major camps also contain significant physical evidence worthy of preservation and are identified by historical markers. Several camps are visited annually by reunion groups of former detainees, their families, and friends who work to preserve physical remains and memories of internment experiences.

Department of Justice Internment Camps

The Department of Justice was responsible for three types of facilities: temporary detention camps run by the Immigration and Naturalization Service; comfortable diplomatic "hotel camps;" and "enemy alien" camps for noncitizen Italians, German Americans, Japanese removed from Latin American countries, and others. These facilities were populated with families and individuals who were regarded as a "potential danger to the Nation."(11) Approximately 1,600 Italian citizens and travelers were interned and thousands of Italian Americans were forced to move or comply with travel restrictions. Although exact figures differ, at least 6,300 German Americans and about 300 Italians deported from Latin America were detained, although many were later paroled and released. Approximately 2,200 Latin-American Japanese were classified as "enemy aliens" and held at special home front camps separate from Japanese Americans.

As an example, the Crystal City Internment Camp for "enemy aliens," one of three established in Texas, was a 500-acre complex of 41 cottages, 188 one-room structures, and service buildings such as warehouses, offices, schools, grocery stores, a hospital, and a swimming pool. In 1945, its 3,325 detainees who spoke Japanese, German, Spanish, Italian, and English lived in housing separated by nationality. They worked in camp shops and offices; raised vegetables, pigs, and chickens; made ethnic foods for sale; and assisted in school and camp administration. Although the Crystal City camp "resembled a bustling small town," 10-foot high fences, guard towers, floodlights, and guard patrols constantly reminded detainees of their lack of freedom. The Crystal City camp was the last "enemy alien" facility to close.

Over the past two decades, German-American families have held reunions at the camp. In November 2002, Crystal City and the Zavala County Historical Commission hosted the "First Multi-Ethnic National Reunion of World War II Internment Camp Families." Approximately 150 German and Peruvian-Japanese families were represented. Today, part of the camp is open terrain and structural foundations are present near a 1985 plaque.(12) Other important "enemy alien" camps were located at Fort Missoula, Montana; Kooskia, Idaho; Seagoville, Texas; and Fort Stanton, New Mexico.(13)

Department of the Army Prisoner-of-War Camps

German military personnel taken prisoner in North Africa during 1943 were the first enemy troops brought to American wartime prisoner-of-war or "PW" camps.(Figure 3) By June 1945, more than 425,000 Axis prisoners—371,000 Germans, 50,000 Italians, and 4,000 Japanese—were housed in about 125 main camps and 425 smaller branch camps across the country.(14) Usually located in rural, isolated regions of the country, PW camps became curiosities to nearby towns, desirable economic boosts to counties, and reminders of the overseas war to neighbors.

|

Figure 3. A German prisoner-of-war in work clothes at the Nyssa prisoner-of-war camp in Oregon was photographed in May 1946. (Courtesy of the Oregon State Archives.) |

Since 1996, Professor Michael R. Waters of Texas A&M University has been investigating Camp Hearne in Texas. Archeological test excavations, extensive archival research in American and German military records, oral histories with former guards and prisoners, and local historical research produced the first comprehensive understanding of a home front prisoner-of-war camp. Foundations for the mess hall, theater, barracks, decorative ponds, and fountains have been documented, and everyday artifacts recovered. The report, Lone Star Stalag, offers accounts of prisoners' daily lives and operations, including Nazi followers' violent intimidation of fellow prisoners, relationships between guards and townspeople, and artifacts recovered from the site.(15) Nominations to the National Register of Historic Places and to the Texas State register are in preparation.

Only one other PW camp has undergone an archeological study. Test excavations at Camp Carson in Colorado did not yield significant evidence, but PW camps in Missouri, Iowa, Oklahoma, and New Mexico have been researched by historians. These studies include descriptions of PW involvement with local agricultural production and construction projects as well as soccer games, the barter of handicraft items, and some postwar marriages with American women. Research also provides contrasts in how German and Italian officers and enlisted men adapted to confinement as they attempted to follow their national cultural and political expressions, including Nazi, Fascist, and religious art; soccer teams; food; camp newspapers; crafts; sculpture; and musical performances.(16)

Civilian Public Service Camps

Executive Order 8675 issued February 6, 1941, established the Civilian Public Service (CPS) as an alternative obligation for conscription-age men.(17) Approximately 12,000 male conscientious objectors and 300 women entered civilian public service. Nearly all were active members of Mennonite congregations, Church of the Brethren, and the Society of Friends (Quakers), churches which became administrators of CPS facilities in about 30 states. Enrollees performed many important tasks from firefighting to assisting in social service programs, but they experienced restrictive daily routines. No inventory of remaining CPS facilities has been undertaken, but some former Depression-era structures used as CPS camps may exist on U.S. Forest Service or national park lands. Former CPS enrollees have an alumni organization and some have revisited their wartime camp locations.

Unangan Native Peoples' Camps

Aleutian Island warfare in 1942-43 forced removal of about 800 Unangan or Aleut Alaska Native people from their islands as "a military necessity" to protect them from Japanese bombing. Abandoned canneries, 1930s Civilian Conservation Corps camps, and a former gold mine became substandard "duration villages" in southeastern Alaska for the displaced people, and were operated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The Unangan could not bring many possessions from their home villages, but still persisted as a cultural group in spite of great hardship. They were included in the 1988 Japanese-American restitution legislation.(18)

Military Facilities

Seattle, San Diego, the San Francisco Bay area, New York City's port complex, Gulf Coast cities, New England harbors, and Alaskan towns housed World War II-related armaments, defensive fortifications, and support bases.(19) World War II defensive installations are in varying stages of preservation or deterioration. Within Cabrillo National Monument near San Diego, a well-preserved four-155mm-gun coastal defense battery constructed in 1941 has been documented with archeological methods and oral history.(20)(Figure 4)

|

Figure 4. This view of the Coastal Defense Battery Point Loma, CA, in 1941 shows the stabilized Gun Mount #4. (Courtesy of the Cabrillo National Monument, National Park Service.) |

At the mouth of the Delaware River in Delaware, Fort Miles Army Base was constructed during 1941 to defend refineries and industrial complexes. A Coast Artillery division manned searchlights, operated several 155mm 1918-model mobile guns, and deployed mine systems. Several tall circular concrete towers used for triangulation of ship positions for battery fire control exist today. Many of the structures are within Delaware's Henlopen State Park where public information about the former Fort Miles is available.(21) In Portsmouth, New Hampshire, home front defensive structures are extant within local and state parks. A former Navy communications facility is located within Acadia National Park in Maine and an early coastal radar station is preserved in Redwood National Park in California.

Military training facilities include the huge "Desert Training Center" in California and Arizona. Evidence of General George S. Patton's desert command post, division-size camps, and support facilities exists on Bureau of Land Management lands.(22) A museum near Indio, California, relates Patton's career and the significance of the center to military preparedness. The Army Air Corps quickly developed hundreds of home front airfields, gunnery ranges, auxiliary bases, and training facilities, which included thousands of women pilots, flight instructors, and support personnel. Many locations retain airfield layouts and building complexes.(23)

The compelling story of the Tuskegee Airmen has shown how courageous African-American pilots and their male and female support personnel fought national prejudice as well as Axis enemies.(24) Moten Field near Tuskegee, Alabama, includes an extant hangar, control tower, parachute loft, and roadways from the original complex of 15 structures. The Airmen's veterans group and preservation of the Moten Field facilities as part of a national park has expanded public awareness of African-American contributions to the wartime aviation effort in spite of segregated armed forces.

A major attack by Japanese Imperial forces on the Dutch Harbor Naval Operating Base and Fort Means, Alaska, in June 1942 brought deadly combat to United States soil. Brutal fighting on Kiska, Amchitka, Unalaska, and Attu Islands resulted in heavy losses on both sides due to the weather, poorly equipped American forces, bombing, and tenacious resistance. A visitor center for the Aleutian World War II National Historic Area on Unalaska Island will open in 2004 to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the Aleutian Campaign which brought war and the Unangan peoples' displacement directly to the American home front in Alaska.(25)

Industrial Facilities

Retooling America's industrial strengths from peacetime consumerism to wartime production required the intense coordination of national economic, political, and technical energies. The War Resources Administration (WRA) and myriad other bureaus implemented this transformation. Places cited below are examples of historic architecture, potential industrial archeology, and the breadth of American industry during wartime. Thousands of ships were constructed at nearly 150 Federal Government and contract shipyards, including the famous Liberty and Victory classes for troop and munitions transport.

Peacetime land use has removed many private-sector shipyards, but dry-docks at Kaiser Company Shipyard #3 in Richmond, California—located within the boundaries of Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front National Historical Park—retain historical integrity.(Figure 5) Aircraft manufacturers and suppliers operated in at least 15 states. Due to labor shortages, Douglas, North American Aviation, Boeing, Grumman, Bell, Hughes, and Lockheed employed many minority men and women at plants in southern California towns as well as in Seattle and other industrial cities. Some Lockheed and Boeing plants were camouflaged to resemble housing and grain fields. A few historic structures remain at some locations.

|

Figure 5. During the years from 1942 to 1944, Dorothea Lange captured many images of Kaiser's Richmond, CA, Shipyard, including this photograph of women workers in a paycheck line. (Courtesy of the Oakland Museum of California.) |

The top-secret Manhattan Project and its Hanford Engineer Works B Reactor, near Richland, Washington, has required Superfund environmental restoration work. A National Register nomination covering Hanford's prehistory, historic, and World War II properties was prepared. Building inventories, archeological testing, and archives of historic photographs and documents were also completed.(26)

At the former Concord Naval Weapons Center near Concord, California, a munitions shipping installation with numerous bunkers, rail sidings, a chapel, and administrative buildings are collectively known as Port Chicago. Here, the "Port Chicago Explosion" on July 17, 1944, killed 320 men, 202 of whom were African American. The refusal by 50 men to continue to work in hazardous conditions led to courts-martials and prison sentences, but by 1946, most sailors were released and discharged. In 1994, Congress established the Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial where an annual survivors' commemoration ceremony is held near the piers where two ammunition ships exploded.(27)

Civilian Facilities

The relocation of 15 million workers and their families to assembly plants, military bases, and shipyards had significant impact on the experiences of civilians during the war. The Federal Works Agency, Federal Public Housing Authority, major contractors, and city housing commissions developed these facilities. Wartime migration brought major changes to family life and the workplace at major defense industry centers. While racial prejudice continued in government and private housing markets, the scarcity of trainable workers caused defense industry firms to change their recruitment practices to accept women and minority applicants. At the workplace, significant numbers of women and minority workers performed tasks with nonminority males to meet or exceed production goals. Atchison Village, an example of defense worker government housing for 450 shipyard families in Richmond, California, is now included in Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front National Historical Park.

To house military personnel, Atomic Energy Commission staff, and Dupont employees, Richland in Washington State was constructed as a complete "federal town" for about 11,000 people. Nearly 20 housing types—each identified by a letter of the alphabet—were built and assigned based on family size and job status. Some current residents of Richland occupy upgraded Alphabet Houses and are employed in the Hanford Project's Superfund clean-up programs. The Columbia River Exhibition of History and Technology Museum in Richland offers exhibits on the Hanford Project and a new World War II "1940s Trailer Living" exhibit.(28)

Two Japanese American pre-war urban communities have continued as ethnic districts. Japantown in San Jose, California, is one of the most intact representatives of Japanese-American urban community life in the nation. The establishment of a historic district, a memorial sculpture, and programs sponsored by a local council and the Japanese American Museum of San Jose are funded from preservation grants.(29) On Bainbridge Island in Washington State, Japanese Americans who returned to their homes after internment are active in planning for a commemorative public park.

Using Home Front Heritage in Modern Society

Identification of home front heritage locations at local, state, and national levels is impressive, but far from complete. Many World War II historic resources have lost integrity; others are recognizable only from remnants. Some are reasonably intact as combinations of archeological and architectural resources, historic landscapes with visible features, and deep emotional associations for particular people. Most states include World War II places in their historic registers, but some cities, counties, and states have not fully addressed their role during the home front era.

Public education programs regarding local wartime heritage exist in some urban and regional museums, particularly those focused on military units, group ethnicity, and internment camps. Home front national life as a museum education topic is increasing, often where places or significant buildings exist or threshold events occurred. Museum programs and special exhibits depicting home front themes may well increase as wartime anniversary events are planned. More oral histories are needed from participants while still available. Aviation museums display aircraft manufactured at home front plants, often by interracial work crews whose stories should accompany the historic planes.

Pilgrimages, reunions, and gatherings will contribute towards emotional closure, informing younger generations and increasing public awareness. The participants in these events can also act as site stewards to commemorate, monitor, and preserve the resources and the value of their experiences at a place.

The development of heritage tourism surrounding World War II places is beginning. Some states have online tourism information to guide visitors to wartime historic sites as well as recreation opportunities. A National Register of Historic Places travel itinerary for the World War II home front in the San Francisco Bay region is available.(30) Tour routes linking a variety of home front sites can give 21st-century Americans a more balanced understanding of the heroic and everyday aspects of global wartime's impact at home.

Preserving archeological and architectural resources related to World War II requires creative thinking by groups and individuals. Site resource inventories, the consideration of impacts of memorial projects, and protection from relic hunters and encroachment are very important elements for future site integrity, significance, and meaning. Preservation easements with private landowners may be useful to achieve some protection objectives.(31) Listing in the National Register of Historic Places, designation in state and local historic property registries, and other forms of recognition give an official status to a place, often requiring public consideration for zoning or land use changes.

Finally, home front sites and their messages to the American people can best be developed and transmitted by interdisciplinary and cooperative work among specialists, original participants, elected and other officials, and neighboring residents. An open planning process of appropriate scale for the heritage property is essential. A time frame of many years' duration may be needed. Communication plans and websites may be effective and inexpensive ways to reach a broad audience. The recognition of the civic, economic, and historic community values of World War II home front heritage is basic to preserving our nation's cultural resources.

About the Author

Roger E. Kelly is senior archeologist with the Pacific West Region, National Park Service, in Oakland, California. His education began in a barracks primary school in Richland, Washington.

The author gratefully acknowledges assistance from the following individuals: Linda Cook, manager, Aleutian Island WWII National Historic Area; Karl Gurcke, a historian with Klondike Gold Rush National Historic Site, whose family was held at Crystal City; Rolla Queen, archeologist, Bureau of Land Management Desert District; Anne Vawser, Midwest Archeological Center, National Park Service; Michael R. Waters, professor of anthropology, Texas A&M University; John P. Wilson, consultant, Las Cruces, New Mexico; and reviewers of earlier drafts of this article.

Notes

1. See for example John Morton Blum, V Was For Victory: Politics and American Culture During World War II (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976); John W. Jeffries, Wartime America: The World War II Home Front (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1997); Roger W. Lotchin, ed., The Way We Really Were: The Golden State in the Second World War (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999); Roger W. Lotchin, The Bad City in the Good War: San Francisco, Los Angeles, Oakland, San Diego (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2003); Ronald Takaki, Double Victory: A Multicultural History of America in World War II (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2000); and Allan M. Winkler, Home Front U.S.A.: America During World War II (Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 2000).

2. Many authors have addressed Great Britain's home front. The following are excellent examples of British heritage preservation overviews: C. S. Dobinson, J. Lake, and A. J. Schofield, "Monuments of War: Defining England's 20th Century Defence Heritage," Antiquity 71, No. 272 (1996): 288-298; Christine Finn, "Defiant Britain: Mapping the Bunkers and Pillboxes Built to Stymie a Nazi Invasion," Archaeology 53, No. 3 (2000): 42-49; J. Anthony Hellen, "Temporary Settlements and Transient Populations: The Legacy of Britain's Prisoner of War Camps: 1940-1948," Erdkunde (University of Bonn) 53, No. 3 (1996): 191-211; David McOmish, David Field, and Graham Brown, Field Archaeology of the Salisbury Plain Training Area (London: English Heritage, 2002); John Schofield, "Conserving Recent Military Remains: Choices and Challenges for the Twenty-First Century" in Managing Historic Sites and Buildings: Balancing Presentation and Preservation, ed. Gill Chitty and David Baker (London: Routledge and English Heritage, 1999), 173-186.

3. The draft World War II National Historic Home Front theme study is under review. Its status is reported on the National Historic Landmarks website, http://www.nps.gov/nhl/

4. Fort Carson is addressed in Melissa A. Conner and James Schneck, The Old Hospital Complex (5EP1778), Fort Carson, Colorado (Final Technical Report), prepared for the Directorate of Environmental Compliance and Management, Fort Carson, CO, by the Midwest Archeological Center (Lincoln, NE: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1996); James Schneck and Karin M. Roberts, Waste Water Treatment Plant and Incinerator Complex (5EP2447 and 5EP2446), prepared for the Directorate of Environmental Compliance and Management, Fort Carson, CO, by the Midwest Archeological Center (Lincoln, NE: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1996). The Presidio military complex is addressed in Presidio of San Francisco: Historic Structures Adaptive Reuse Study, prepared for Jones & Stokes Associates, Inc. (Sacramento, CA: Page & Turnbull, Inc., 1989). Fort Mason is addressed in R. Patrick Christopher and Erwin N. Thompson, Historic Structure Report: Western Grounds-Old Parade Ground and MacArthur Avenue (San Francisco, CA: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1979).

5. A recent overview of the wartime evidence in Hawaii and the Pacific is available from Rex Alan Smith and Gerald A. Meehl, Pacific Legacy: Image and Memory from World War II in the Pacific (London and New York: Abbeville Press, 2002).

6. The TRACES conference page is http://www.traces.org/WWIIstudiesconferences.html accessed February 18, 2004; Richard E. Osborn, World War II Sites in the United States: A Tour Guide & Directory (Indianapolis, IN: Riebel-Roque Publishing Co., 1996); The Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles hosts an annual "All Camps Conference" for former detainees, families, educators, researchers, and others.

7. For example, see the following: The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997); Stephen Fox, The Unknown Internment: An Oral History of the Relocation of Italian Americans during World War II (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1990); Arnold Krammer, Nazi Prisoners of War in America (New York: Stein and Day, 1979); Edward H. Spicer, Asail T. Hansen, Katherine Luomala, and Marvin K. Opler, Impounded People: Japanese Americans in the Relocation Centers (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1969); Erica Harth, ed., Last Witnesses: Reflections on the Wartime Internment of Japanese Americans (New York: Palgrave for St. Martin's Press, 2001)

8. For example, see Prisoners in Paradise, produced and directed by Camilla Calamandrei, 60 minutes, distributed by Camilla Calamandrei, P.O. Box 1084, Harriman, NY 10926, 2001, videocassette; and Nazi POWs in America, produced and directed by Sharon Young, 50 minutes, Arts and Entertainment Television Networks, 2002, videocassette.

9. Jeffery F. Burton, Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord, and Richard W. Lord, Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites, Publications in Anthropology No. 74, Western Archeological and Conservation Center (Tucson, AZ: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1999).

10. Jeffery F. Burton, Three Farewells to Manzanar: The Archeology of Manzanar National Historic Site, California, Publications in Anthropology No. 67, Western Archeological and Conservation Center (Tucson, AZ: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1996); Jeffery F. Burton, Jeremy D. Haines, and Mary M. Ferrell, Archeological Investigations at the Manzanar Relocation Center Cemetery, Manzanar National Historic Site, Publications in Anthropology No. 79, Western Archeological and Conservation Center (Tucson, AZ: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2002); Glenn D. Simpson, Manzanar National Historic Site: Historic Preservation Report: Record of Treatment, Return of Historic Mess Hall to Manzanar National Historic Site (Santa Fe, NM: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, n.d.); Harlan Unrau, The Evacuation and Relocation of Persons of Japanese Ancestry During World War II: An Historical Study of the Manzanar War Relocation Center, Denver Service Center (Denver, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1996).

11. "Enemy Alien" camps and the confinement of American civilians of Italian and German ancestry during the war years has not received public attention equal to the Japanese-American experience but coverage in some print media and online sources is increasing. See James Brooke, "After Silence, Italians Recall the Internment," at German Americana, http://www.serve.com/shea/germusa/itintern.htm, accessed February 18, 2004; Emily Brosveen, "World War II Internment Camps," at the TSHA Handbook of Texas Online, http://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online, maintained by the Texas State Historical Commission, accessed February 18, 2004; Fox, The Unknown Internment; Arthur E. Jacobs, "World War II, The Internment of German American Civilians," at The Freedom of Information Times, http://www.foitimes.com/internment, accessed February 18, 2004.

12. Craig Gima, "In a Small Town in Texas…," Honolulu Star-Bulletin, November 8, 2002; Rebeca Rodriguez, "This Time They're Free," San Antonio Express-News, November 10, 2002.

13. Priscilla Wegars, "Japanese and Japanese Latin Americans at Idaho's Kooskia Internment Camp," in Guilt by Association: Essays on Japanese Settlement, Internment and Relocation in the Rocky Mountain West, ed. Mike Mackey (Powell, WY: Western History Publications, 2001), 145-183; Wegars, Golden State Meets Gem State: Californians at Idaho's Kooskia Internment Camp, 1943-1945 (Moscow, ID: Kooskia Internment Camp Project, 2002); Carol Van Valkenburg, An Alien Place: The Fort Missoula, Montana, Detention Camp, 1941-1944 (Missoula, MT: The Pictorial Histories Publishing Co., 1995); John Joel Culley, "Troublesome Presence: World War II Internment of German Sailors in New Mexico," Prologue [National Archives and Records Administration] 28, no.4 (1996): 279-295.

14. Krammer, Nazi Prisoners of War in America.

15. Michael R. Waters, Lone Star Stalag: German Prisoners of War at Camp Hearne, Texas in World War II (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2004).

16. Anonymous, "The McLean Prisoner of War Camp" at the Devil's Rope Museum online, http://www.barbwiremuseum.com/POWCamp, accessed February 18, 2004; Ken Sullivan, "Thousands of German Prisoners held in Iowa," at the Cedar Rapids Gazette online, http://www.gazetteonline.com/special/homefront/story30.htm, maintained by Gazette Communications, accessed February 18, 2004; Melissa A. Connor, Julie S. Field, and Karin M. Roberts, Archeological Testing of the World War II Prison-of-War Camp (5EP1211) at Fort Collins, El Paso County, Colorado, prepared for and funded by The Directorate of Environmental Compliance and Management, Fort Carson, CO., Midwest Archeological Center (Lincoln, NE: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1999); Mike Garrett, "POW Camp Once Beehive of Activity," in The Durango Herald, August 10, 2003, 5A; Richard S. Warner, "Barbed Wire & Nazilagers: POW Camps in Oklahoma," Chronicles of Oklahoma vol. LXIV, no. 1 (Spring 1986); "Basic Facilities of POW Camps" at Okie Legacy online, http://okielegacy.org/WWIIpowcamps/powcamp4.html, and "It was called Nazilager (Nazi Camp)," at the Okie Legacy online, http://okielegacy.org/WWIIpowcamps/powcamp2.html, accessed February 19, 2004; Janet Worral, "Prisoners of War in Colorado—A Lecture," presented to the Fort Collins Historical Society, February 1995.

17. Civilian Public Service program and conscientious objectors' camp life is described in references below but few actual locations have been identified: Cynthia Eller, Conscientious Objectors and the Second World War (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1991); Joyce Justice, "World War II Civilian Public Service: Conscientious Objector Camps in Oregon," in Prologue 23, no. 2 (Fall 1991): 266-273; Albert N. Keim, The CPS Story: An Illustrated History of Civilian Public Service (Intercourse, PA: Good Books, 1990).

18. Levi Long, "WWII Internments set Aleuts adrift from their islands," Seattle Times, February 19, 2004. See also the brochure, "'Unangax Tenganis' Our Islands, Unalaska," Aleutian WWII National Historic Area Map and Guide (Anchorage, AK: National Park Service, n.d.).

19. Key references to examples of America's coastal defense systems are found in the following publications: Dale E. Floyd, Defending America's Coasts, 1775-1950: A Bibliography (Alexandria, VA: United States Army Corps of Engineers, 1997); Erwin N. Thompson, Historic Resource Study: Seacoast Fortifications, San Francisco Harbor (Denver, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1979); Barry A. Joyce, A Harbor Worth Defending: A Military History of Point Loma (San Diego, CA: Cabrillo Historical Association, 1995); Joel W. Eastman, "Casco Bay During World War II," online at http://www.cascobay.com/history/history.htm, maintained by Casco Bay Online, accessed April 20, 2004; Jack P. Wysong, The World, Portsmouth and the 22d Coast Artillery: The War Years 1938-1948 (Missoula, MT: Pictorial Histories Publishing Co., 1997).

20. Brett Jones and Howard Overton, Project Report: Battery Point Loma 155 mm Gun Emplacement Preservation (San Diego, CA: Cabrillo National Monument, National Park Service, 1984).

21. "Fort Miles Army Base, Lewes, DE: Home of the 261st Coastal Artillery Division, a Great Fortress in the Dunes at Cape Henlopen," http://www.fort-miles.com, accessed February 19, 2004.

22. Matt C. Bischoff, The Desert Training Center/California-Arizona Maneuver Area, 1942-1944 (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2003).

23. Lou Thole, Forgotten Fields of America, Then and Now (Missoula, MT: Pictorial Histories Publishing Co., 1996, 1999).

24. Lynn M. Homan and Thomas Reilly, The Tuskegee Airmen (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 1998).

25. See the following brochures: Aleutian World War II National Historic Area, "The Battle of Attu," (Anchorage, AK: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, n.d.); idem, "The Occupation of Kiska," (Anchorage, AK: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, n.d.).

26. Aircraft manufacturers and assembly plants are listed at http://www.acepilots.com/planes/factory.html, accessed June 14, 2004.

27. See Tracey Panek, "Challenge to Change: The Legacy of the Port Chicago Disaster," Common Ground (Summer 2004): 16-25.

28. Darby C. Stapp, Joy K. Woodruff, and Thomas E. Marceau, "Reclaiming Hanford," Federal Archeology, vol. 8, no. 2 (1995): 14-21. Brief descriptions of the exhibits are available at the Columbia River Exhibition of History and Technology Museum's website, http://www.crehst.org, maintained by Team Battelle, accessed February 19, 2004; Rick Hampson, "World War II Changed Americans More Than Any Other Event," Las Vegas Review-Journal August 2, 1995, 7B. For more on the "Alphabet Houses," see excerpt from the 1943 "Report on Hanford Engineer Works Village: General Building Plans," by G. Albin Pherson, which details the housing types and provides drawings. See "The House that Hanford Built" at http://hanford.houses.tripod.com/GenBldgPlans.html, accessed February 19, 2004.

29. Janice Rombeck, "Preserving Japantown: S. J. historic district begins pilot program," San Jose Mercury News, March 8, 2004, 1B-4B.

30. http://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/wwIIbayarea/

31. Susan L. Henry, Geoffrey M. Gyrisco, Thomas H. Veech, Stephen A. Morris, Patricia L. Parker, and Jonathan P. Rak, Protecting Archeological Sites on Private Lands (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1993); Deborah Bruckman Maylie, Historic Preservation Easements: A Directory of Historic Preservation Easement Holding Organizations (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1998). See also the 2000 update of "Strategies for Protecting Archeological Sites on Private Lands," at http://tps.cr.nps.gov/pad/index.html, accessed March 31, 2004.