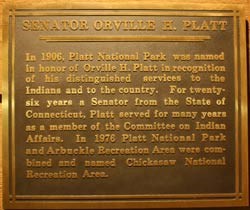

NPS/Amy Trenkle One of the more unusual features of Platt National Park was that the park name memorialized a person not directly tied to the place. Visitors often ask, "Who was Platt and why did he get a park named for him?" During Senator Platt's final years in the United States Senate, he was actively involved in Indian Affairs and the work of the Dawes Commission. It was Senator Platt who sponsored the original legislation to establish the park as the Sulphur Springs Reservation in 1902. His work to keep the mineral springs found here accessible to all Americans was honored by Congress in 1906 when they directed that the Sulphur Springs Reservation be redesignated Platt National Park.

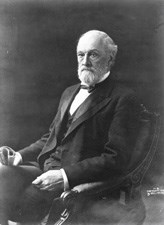

Library of Congress Orville Hitchcock Platt (July 19, 1827 - April 21, 1905) was a United States Senator from Connecticut. Born in Washington, Connecticut, he studied law in Litchfield, and was admitted to the bar in 1850, commencing practice in Towanda, Pennsylvania. He moved to Meriden, Connecticut in 1850 and continued to practice law. He served in various positions in the Connecticut state government between 1855-1857 and was a member of the State senate in 1861 and 1862, and a member of the Connecticut House of Representatives in 1864 and 1869. Platt was state's attorney for New Haven County, 1877 to 1879, and was elected as a Republican to the U.S. Senate in 1879. He served in the Senate from March 4, 1879, until his death, for many years as a member of the Committee on Indian Affairs. Platt died on April 21, 1905, aged 77, in Meriden, and was interred in Washington, Connecticut in the Cemetery on the Green.

1915 report image Exerpt from the Joint Report of the Commissions on Memorials to Senators Orville Hitchcock Platt and Joseph Roswell Hawley to The General Assembly of the State of Connecticut (1915)Hon. John C. Spooner, introduced by Mr. Lines, delivered the following address on Senator Platt: Mr. Chairman, Ladies and Gentlemen: We are here today to carry into effect, by appropriate ceremonial, a well-deserved tribute by the Commonwealth of Connecticut to two of her best loved sons, Orville H. Platt and Joseph R. Hawley, upon whom she steadfastly conferred the highest honor within the gift of a state — by choosing them to represent her in the Senate of the United States. The part assigned to me in this ceremonial is to speak of Orville Hitchcock Platt — a senator of the United States for over a quarter of a century from this commonwealth, with whom I was associated in that service for fifteen years. To me it is a labor of love, as for years we lived under the same roof, and until " God's finger touched him and he slept," I was honored by his friendship and unreservedly admitted to his confidence. It is not possible under the limitations of the occasion, nor is it at all needful in Connecticut, to dwell in detail upon his boyhood, or the circumstances in which he grew to manhood. It is enough to say that he came of an ancestry, strong-fibered, liberty-loving and God-fearing. He was born upon a farm, owned and tilled by his father, who had been described by one who knew him as "A man of fine face and figure, intelligent, kindly and courteous, as one who took a prominent part in the politics of the town and religious meetings, and was forcible, modest and a convincing speaker." Of his mother the same person has written : — "That she was a stately, handsome woman, quiet in manner, prudent in speech, but positive in her convictions; finding her greatest pleasure in the life of the home, attention to her domestic duties, reading the Scriptures and standard works and teaching her boys by precept and example the virtues of goodness, charity, sobriety and whatever else contributed to the development of sturdy self-reliance and manly manhood." The people of Connecticut need not to be told of his ancestry, the environment of his youth, or the circumstances which developed his manhood. It is enough to say that he possessed the conscience of the Puritan, that he early learned the lessons of self-denial and self-help, that he was a hard and faithful worker in the school and in the field. In the one he acquired knowledge and mental discipline, in the other he developed that great physical vigor, which enabled him to honor at sight every draft made thereon during his long and arduous life. Contemporaneous with his birth and youth was the agitation against African slavery in the United States. The father and mother of Senator Piatt were abolitionists and the struggle between freedom and slavery became acute in the neighborhood in which was his home. It divided congregations. It suppressed the school in which he was a student, and in which later he was an instructor; it attached him irrevocably to the principles of liberty. The lessons which he learned in his youth and which were confirmed in his maturity he adhered to " without variableness or shadow of turning " to the hour of his death. It is quite impossible to dissociate from his career the convictions which came in his youth. They were taught him by his father and his mother. They became part of his conscience and his very being. To hate oppression and injustice was a part of his youth, and it was a part of his manhood. Perhaps the ceaseless and powerful struggle, involving immense labor for years in the Senate, to protect the Indian tribes from injustice and the rapacity of the white man, in violation of treaty rights, was due somewhat to the teachings of the fireside of his boyhood home. It was a work which was near to his heart, and no one know better than he that in its performance he invited the hostility of the influential, and that the gratitude of the Indian, albeit sincere, would be silent and unimpressive. Senator Morgan of Alabama well said in the eulogy which he pronounced upon Senator Piatt, referring to his work in the committee on Indian affairs : — "The proud and silent nod of the grateful Indian in approbation of the equally proud and silent assistance of the great senator was the only token of friendship between men who were sternly just in their actions, and neither of them asked nor expected nor granted favors." Industry and Fidelity in StudyHe was enabled to acquire under the tutelage of a gifted teacher, and through his own industry and fidelity in study, an excellent education and a power of investigation and analysis which was evidently quite phenomenal. It is no surprise, when we keep in mind the characteristics of his youth, his industry and aptitude for acquiring knowledge, that he chose as his life work the profession of the law. That as a lawyer he was industrious, honorable and able is well attested by his success in the profession. The friends he gained, who still survive him, are still his friends. It is said that his practice in Meriden, then, of course, much smaller and less important than the Meriden of today, became large and lucrative. He early won the confidence of those among whom he lived. He was honored with positions locally and in the state on several occasions, having served a term as state's attorney of the county, and as secretary of state, besides having been speaker of the House of Representatives of Connecticut, and ultimately he was chosen in a highly honorable way for the United States Senate by the General Assembly in January, 1879, and took his place in that august body on March 18, 1879, and from that day to the day of his death represented Connecticut therein. While appreciating the great honor conferred upon him by the State of Connecticut, he did not regard it as an honor, simply to be a senator of the United States, but rather he looked upon it as a great opportunity afforded to him by the commonwealth in which he was born, and to which he was devoted, to achieve for his state and for himself honor, by laborious and faithful service as a senator. A man fit to be a senator suddenly ushered into that body without previous experience in federal legislation, charged equally with those of large experience there with the intelligent solution of the varied problems with which the Senate has to deal, is very likely to regret for a time that success had crowned his ambition to become a senator. Orville Hitchcock Platt, while self-reliant and self-respecting, was withal a modest man, and, with that good sense which always characterized him, he determined to fit himself for the duties which inhere in the office by patient and dilligent study of each subject with which as a senator he was obliged to deal. From the day he entered it to the end of his service, he gave without stint to every question involving the public interest, the painstaking investigation and reflection required to enable him to reach a correct conclusion. He put to good use in the public service the habit of work which he had acquired in his youth; the power of investigation which he had acquired in the schools, and in the study of the law and in the practice of his profession, and of the public questions with which he had been obliged to deal as a citizen and state official. He was essentially in all the relations of life a faithful man, loyal to his convictions, and persistent in fitting himself to discharge well every duty imposed upon him or intrusted to him. His Aim as a SenatorHe entered the United States Senate with a determined purpose to make of himself what the people of Connecticut desired and expected him to be — what the people of the United States have a right to demand that a senator of the United States shall be. He realized from the beginning, what some who have been in his position have not been so quick to realize, that, while a senator is chosen by his state, he is not a senator of the state which chose him, but he is a senator of the United States from the state which chose him. Rightly regarding his election to the Senate as affording him the honor of an opportunity to win for his state and for himself by able and devoted service to the people of the United States, he gave the best that was in him to the right solution of public questions and to the advocacy and promotion of sound policies. Loyal always to Connecticut, where any demand of the constituents, in his judgment, conflicted with the general public interest, it may, without fear of contradiction, be asserted of him that there has been no member of that body who with greater single heartedness sought to serve the interests of the people of the United States, and subordinate to that every interest of the people of the state in which he was born and reared, in which all of the associations of his life were centered, and which he not only tenderly loved, but of which he was inexpressibly proud, than did he. He carried into the national public life the same sense of responsibility that a high-minded executor or administrator does in conserving the interest which he represents in a fiduciary way, not only in large things but in small ones. Unless detained from the chamber by illness, he was during the sessions of the body always at his post of duty. He gave attention to every bill on the calendar; he felt it to be his duty to defeat a claim, albeit trifling in amount, if it involved, in his judgment, a wrong or vicious principle, for he knew the power of a wrong precedent in Congressional legislation. It was a part of the education of his boyhood and youth to realize that " many a mickel makes a muckle," and that, whatever one may do with his own, acting in a representative capacity he has no right to sacrifice the interest of those whom he represents whether they be large or small. When a bill came before the Senate, if he arose and said: "Mr. President, let that bill go over," the introducer of that measure, if he knew it was of a doubtful merit, lost hope, for, when it came up again, he could be certain that the senator who had, by a word, stopped it for investigation, would be ready to fight it, approve it, or by amendment eliminate from it some vicious feature, or incorporate some safeguard for the future. As time went on he became a member of committees of larger importance — the committee on territories; the committee on patents; the committee on the judiciary; the committee on finance, and during all the years he kept as fully advised of the decisions of the supreme court upon constitutional and other questions involving federal litigation as if he were engaged in constant practice before that court, and moreover he familiarized himself with the principles of international law. He devoted great study to financial questions, and was one of the strongest and most unflinching advocates of sound principles of finance and currency. He familiarized himself with every phase almost of the tariff, and became familiar with almost every industry affected by it. In the latter years of his laborious service in the Senate, as the result of his steadfast investigation of public questions, his mastery of constitutional and international law, of finance, and economic principles and problems, brought him more and more to the front, and the retirement of senators, who had preceded his entrance to the body, impelled him as a matter of duty to take a more conspicuous position in the constructive work of the Senate and in the debates upon questions of large and far reaching import. In the formulation of public policies and the advocacy of measures of large concern, he had as chairman of the committee on territories, done great work and accomplished great results. He had as chairman of the committee on patents promoted legislation of great advantage to inventors and promotive of the inventive genius of the country. He had led in the enactment of adequate legislation in respect to the copyright, which secured to one a property right in the product of the mind. He had taken a conspicuous part in the debate which attended the enactment of the interstate commerce law. He had opposed the anti-pooling section of that bill, and had strenuously contended that competitive railway companies be permitted to make agreements in respect of rates, subject to approval by the interstate commerce commission, but he had been defeated. My vote was against his proposition, but in justice to him I may be permitted to say here today that I reached the conclusion later that he was right and that I was wrong, and I took the first opportunity afforded me to publicly so avow. His Work on Anti-trust BillDuring the debate on the anti-trust bill, which lasted for weeks, and which from the standpoint of today is not so illuminating in respect of the general principles involved as it seemed then to be, he rendered a service which has not been much referred to, but which should never be forgotten. The bill, introduced December 4, 1889, by Mr. Sherman, and reported by him from the committee on finance, January 4, 1890, was discussed for several weeks, when Senator Piatt made a short speech against it. The bill provided: — "That all arrangements, contracts, agreements between two or more persons, which tend to prevent full and free competition in articles of growth, production and manufacture of any state or territory of the United States with similar articles of growth, production, or manufacture by another state or territory, and all arrangements between such persons which tend to advance the cost to the consumer of any such articles are hereby declared to be against public policy, unlawful and void." Senator Platt said: — "In other words, this bill proceeds upon the false assumption that all competition is beneficent to the country, and that every advance of price is an injury to the country. That is the assumption upon which this bill proceeds. There was never a greater fallacy in the world. Competition, which this bill provides for, as between any two persons, must be full and free. Unrestricted competition is brutal warfare and injurious to the whole country. The great corporations in this country, the great monopolies in this country, are every one of them built upon the graves of weaker competitors that have been forced to their death by remorseless competition. I am entirely sick of this idea that the lower the prices are the better for the country, and that any arrangements made between persons engaged in business to advance prices, no matter how low they may be, is a wrong, and ought to be repressed and punished. The true theory of this matter is that prices should be just and reasonable and fair. No matter who is the producer, or what the article, it should render a fair return to all persons engaged in production, a fair profit on capital, on labor and everything else that enters into its production. With the price of any article I don't care whether wheat or iron; I don't care whether it is corn or silverware, whenever the price of any commodity is far below that standard the whole of the country suffers." He demonstrated his proposition. The words " trade and commerce" were not in the bill. It was directed solely against all contracts and combinations in restraint of full and free competition. Senator Platt completely riddled it. After so doing, he said : — "So, Mr. President, I cannot vote for this bill in the shape in which I think it will come to a vote, or in any shape in which I think it will be perfected. I am ready to go to the people of the state of Connecticut. I have faith and confidence in them, and when I tell them that here is a bill which under the guise of dealing with trusts would strike a greater blow at their entire industries, I know they will see it and understand it, and, if there be a people anywhere in this country who cannot understand it, it is better for a senator to answer to his judgment and his conscience than it is to answer to their misapprehension." The effect of the argument, delivered as it was, was instant. Immediately a motion was made to refer the bill to the committee on the judiciary, with instructions to report within twenty days, and the motion was carried, and it came back from the judiciary committee, of which Senator Platt was a member, with the words " full and free competition " stricken from it, and the words " trade and commerce " inserted in lieu of it, and generally redrafted and as so reported it is upon the statute book today. The supreme court, in its early construction, construed it as if the words "full and free competition " were in it. But after the lapse of many years, and after Senator Piatt had passed away, that court, under the leadership of the present chief justice, struck out the word "competition," and restored the words: "trade and commerce," so as to bring within the act only combinations and agreements which in the light of reason unduly restrain trade and commerce, and to leave open that large field which Senator Piatt saw must in the interest of the people be left for agreements in restraint of competition which promote trade and commerce up to the point where they not only cease to promote but unduly restrain trade and commerce. His intervention clarified the subject and was an incalculable public service. He thought profoundly, and he had convictions, and he had moreover that thing without which convictions are of little, if any, worth — the courage of his convictions. He never seemed to give a thought in respect of any vote, or any speech delivered by him, of its possible effect on his popularity. He never uttered a word in the Senate with the slightest apparent reference to stage effect or public comment. He was true to his convictions. He would not do for any one in Connecticut, however powerful, what he thought to be against the interest of the people of the United States and he would do for Connecticut anything, and did so far as possible, which was, in his judgment, right in itself and compatible with the general interest. He loved popularity — who does not? But he would not purchase it by a surrender of his convictions. He prized inexpressibly the popular confidence and respect, which was evoked by able, loyal and faithful service, and that he gave, and that confidence and respect he received, and, although no longer among us, is receiving today. Problem Following the Spanish WarThe treaty by which the war with Spain was terminated brought to the United States the cession of the Philippines and of Porto [sic] Rico. Spain also relinquished her title and sovereignty to and over the island of Cuba, then in military occupation of the United States. The close of the war brought novel responsibilities and imposed new duties upon this government, involving legislation in respect of the Philippines and of Porto [sic] Rico, presenting questions of grave moment and much intricacy. These questions were much debated in the Senate. The power of the United States to acquire the Philippines was challenged there. Senator Platt in an admirably reasoned and eloquent speech maintained the existence of the power. In that speech he said: — "We are under the obligation and direction of a higher power with reference to our duty in the Philippine Islands. The United States of America has a high call to duty, to a moral duty, to a duty to advance the cause of free government in the world by something more than example. It is not enough to say to a country over which we have acquired an undisputed and indisputable sovereignty ' Go your own gait ; look at our example.' In the entrance of the harbor of New York, our principal port, there is the Statue of Liberty enlightening the world. Look at that, and follow our example! "No, Mr. President. When the Anglo-Saxon race crossed the Atlantic, and stood on the shores of Massachusetts Bay and on Ptymouth Rock, that movement meant something more than the establishment of civil and religious liberty within a narrow, confined and limited compass. It had in it the force of the Almighty; and from that day to this it has been spreading, widening and extending until, like the stone seen by Daniel in his vision, cut out of the mountain without hands, it has filled all our borders, and ever westward across the Pacific that influence which found its home in the Mayflower and its development on Plymouth Rock has been extending and is extending its sway and its beneficence. I believe, Mr. President, that the time is coming, is as surely coming as the time when the world shall be Christianized, when the world shall be converted to the cause of free government, and I believe the United States is a providentially appointed agent for that purpose. The day may be long in coming, and it may be in the far future, but he who has studied the history of this Western World from the 22nd day of December, 1620, to the present hour must be blind indeed, if he cannot see that the cause of free government in the world is still progressing, and that what the United States is doing in the Philippine Islands is in the extension of that beneficent purpose." It is but a little time since he was laid away in the cemetery near which his parents lived and where he was born. The im.promptu speech from which this language is quoted was delivered with great power, intensity, and true eloquence. Since that day the people of China have overthrown an ancient dynasty, forced the abdication of the Emperor, and China is today governed with the approval or acquiescence of her people, by a provisional republican government, which awaits the action of the Chinese people in respect of a permanant constitution and a permanent republican government. This senator from Connecticut spoke with the foresight of a prophet. He possessed that fine insight which is the genius of real statesmanship. The peculiar status of Cuba which was occupied by the army of the United States and under military government, cast upon us not only a grave responsibility but a complicated and perplexing problem. The congress had, in the joint resolution, under which the war was inaugurated, not only decently but wisely disclaimed any purpose to acquire Cuba, from which it followed that we would occupy Cuba only until under our guidance and with our aid the Cuban people could form and maintain a government of their own. It, therefore, became necessary to establish the committee on " relations with Cuba," and Senator Platt by common consent was made chairman of that committee, of which at his earnest request I became a member. When this government became satisfied that the pacification of Cuba was complete, measures were taken under military supervision, by direction of the President, to facilitate the formation by the people of a government of their own, and to that end provision was made for the calling of a convention to frame a constitution. There were many reasons why the people of Cuba in their own interest, as well as in the interest of the United States, should not be permitted to form a government without provisions embodied also in a perpetual treaty with the United States, containing irrevocable safeguards against improvident action weakening their independence, and giving this government a permanent right to intervene for the preservation of Cuban independence; the maintenance of a government for the protection of life, property and individual liberty, and for discharging the obligations with respect to Cuba imposed by the Treaty of Paris on the United States, thence to be assumed and undertaken by the government of Cuba. Senator Platt called a formal meeting of the committee on relations with Cuba, and submitted to the committee a draft of what is known as the Platt amendment, which, with slight, if any, changes was adopted by resolution of the committee on February 26, reported by the chairman to the Senate, and on the same day offered by him as an amendment to the army appropriation bill then pending, and adopted on the 27th of February by a vote of 43 to 20, a strict party division. While limiting the power of Cuba, it was intended to *safeguard the independence of Cuba, and it is not susceptible of doubt that such has been, and "in the long reach of time " will continue to be, its effect. Story of the Platt AmendmentIt is known, and justly known, as the "Platt amendment." Some doubt has been cast upon his right to be regarded as its author, and in justice to this able, faithful and splendid public servant, I beg to be permitted to say here what I know about drafting the Platt amendment. One evening Senator Platt came to my working room — we both lived at the Arlington Hotel — where I was dictating letters to my secretary. Senator Platt carried in his hand a paper. He said to me : "Spooner, I am sick with the grip" (and he looked ill). "I wish you would help me put in shape a provision which must be embodied in the constitution of Cuba, or appended to it as an irrevocable ordinance and in a permanent treaty." He handed me the paper referred to. I, of course, promptly acquiesced, and we talked the matter over with reference to what should be added, if anything, to the subjects indicated on his paper. We discussed as I remember the advisability of adding a provision which would safeguard the continued sanitation of the cities of the island, and protect our commerce and our southern ports and people from the ravages of yellow fever and other epidemic and infectious diseases. When we had agreed upon the subjects, I dictated to my secretary, in the presence of Senator Platt (stopping and being stopped now and then for consultation), what it seemed would cover adequately the subjects which we had agreed were necessary to be embodied in it. It was written out, and we went over it carefully together with a view to improving and perfecting its phraseology where it seemed to be called for. I do not remember precisely what these changes, which were verbal, were. There was on the paper which Senator Platt handed to me, a memorandum of every subject which is embraced in the Piatt amendment, excepting the clause in respect of sanitation. We agreed upon it and I directed my secretary to make three fair copies, so that we could have them early the next morning, at which time I gave two to Senator Platt and kept one myself, and at his request I accompanied him to the White House. President McKinley promptly received us, and Senator Platt handed him a copy of the draft. He read it carefully and announced that it was precisely what he wanted. He asked Senator Piatt for a copy, which he said he wished to send to Secretary Root as soon as he could. Whether Senator Platt gave him his copy, or I gave him mine, I do not remember, but one or the other of us gave him a copy. That day it was presented informally to members of the committee, who were called together for the purpose, and carefully considered. If any changes were made in it, and I do not remember that any were made, they were very trifling ones. The democratic members treated it fairly and while not willing to vote for it — and it was out of order as being general legislation on an appropriation bill, and if objected to would necessarily have been ruled out of order — even those who recorded their votes against it forbore to raise a point of order and it went into the bill and became a law. He undoubtedly had consulted others, but it would be at variance with his conduct through life for him to permit to be imputed to him the authorship of a document which had been originated and drawn by another. Take him all in all, his great ability, his industry, his fidelity, the high standard which he set for himself as a public servant, his courage, his modesty, his unfaltering loyalty to the public interest, his sincerity, his hatred of sham and demagogy, he was an ideal senator of the United States. An Ideal AmericanHe was an intense American, and thought the Constitution of the United States the finest charter of government ever drafted for a people. He realized that there would be times when the people would grow restless of its restraints and under rash but attractive leadership might stray from the path so wisely and so clearly marked by the fathers who established the government. But he never permitted it to worry him. He realized that one of the purposes which led the people to adopt a written constitution was to protect themselves against themselves in times of passion and excitement. He had an abiding faith in the sober second thought of the American people, and while he thought the people in a relatively small area might en masse make their own laws, pass their own ordinances, and adequately consider and manage their affairs, that in a large territory and population, the only practical government was the representative government established by the fathers of the republic. To him it seemed continuously essential that the independence of the co-ordinate branches of the government should neither be invaded nor diminished, and that the reserved rights of the states should be scrupulously respected. He deemed it vital that the independence of the judiciary throughout the Union should be religiously maintained. He realized that evils and abuses would creep into administration, both in the states and in the nation, but he could not be persuaded that in our country evils or abuses could ever exist, the eradication of which would require the abandonment of any of the fundamental principles of the government under the constitution. The Reward of ServiceHe said once to me — speaking of the sacrifice from some standpoints which public service demanded — that one who entered it and devoted himself to it could see no reward for the toil and sacrifice of such a life but the consciousness that one was really serving the people to his uttermost and was accorded by the people without reserve their confidence, respect, and gratitude. That, he said, among such a people, " is reward enough." He was a loyal friend, a generous colleague, a charming comrade, and, while rather stern in mien at times, was at heart as tender and sympathetic as a woman. You all knew his love of nature; how it delighted him to wander in the woods; to study the trees and the flowers; to listen to the voices of the birds and to the sweet music of the rippling water. It was a long, rugged and toilsome journey from the farm in Judea, to the lofty eminence upon which he died, but he traveled it man fashion, with strong heart, honest purpose, unclouded mind and unafraid. Connecticut has done a just and gracious act by placing in her Capitol this memorial tablet, reproducing his form and features at once a triumph of the artist's skill and a beautiful tribute by tlie state he loved. It was not needed to keep the memory of him alive in the hearts of those who knew and trusted him. But it will be an object lesson, to generations yet to come, in patriotism, personal honor, statesmanship, and supreme loyalty to the highest standard of noble conduct in the service of the people. Whenever Connecticut in the years to come, from time to time shall " count her jewels," she will find among them all — and she has many, and will have more — none more flawless or of finer luster than the life and public service of Orville Hitchcock Platt. |

Last updated: January 23, 2022