Last updated: February 28, 2025

Article

Though Dwelling in a Land of Freedom

Library of Congress

Cuba, Dinah, Malcolm, William, and three children: James and two “small boys” whose names are currently unknown.

These are seven people known to have been enslaved at 105 Brattle Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts as of 1774.1 Late that year, their enslavers abruptly fled Cambridge. This article traces one enslaved family’s journey to that moment, and in the decades of freedom and activism that followed. Research into the life of Cuba (Vassall), her family, and her experiences of enduring slavery and seizing freedom is ongoing.

In 1759, their enslaver John Vassall Jr. built this grand Georgian-style mansion along the Road to Watertown (now Brattle Street), a statement of his incredible wealth. His family had amassed this wealth from their Jamaican sugar plantations, where they enslaved hundreds of people.2 As the sugar industry was dependent on the labor of enslaved Africans, so too was Vassall’s lifestyle. In addition to the enslaved workers on their plantations abroad, John and Elizabeth Vassall also enslaved people at their estate in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The practice of slavery was deeply embedded in the society and economy of the New England colonies, and directly connected to slavery in the Caribbean.

The Vassalls’ financial reliance on slavery was part of a larger regional landscape. As historian Jared Hardesty argues, “slavery built New England’s economy and shaped cultural traditions.”3 Just before the American Revolution, about 4 percent of New England’s population was enslaved, concentrated in urban areas such as Boston (where upwards of 12 percent of residents were enslaved people). People of African descent were enslaved in small scale rural agriculture, in wealthy white households, and in urban industries.4 In Cambridge, a provincial census counted 56 enslaved people in 1754.5

John and Elizabeth Vassall likely forced the seven people they enslaved to work as domestic servants in the house and as laborers in the orchards, garden, small farm, and stables on the estate. Such a large number of enslaved people was unusual in colonial Massachusetts. Although slavery had long existed in the colony, and would persist into the new nation, it was more common for one or two people to be enslaved in a white household.6 Seven enslaved people on a single property reflected the enormous wealth of the white Vassalls, and their commitment to the cruel institution of slavery. In 1774, when the Loyalist Vassalls evacuated their home in the face of revolutionary unrest, the seven people they enslaved remained in Cambridge.

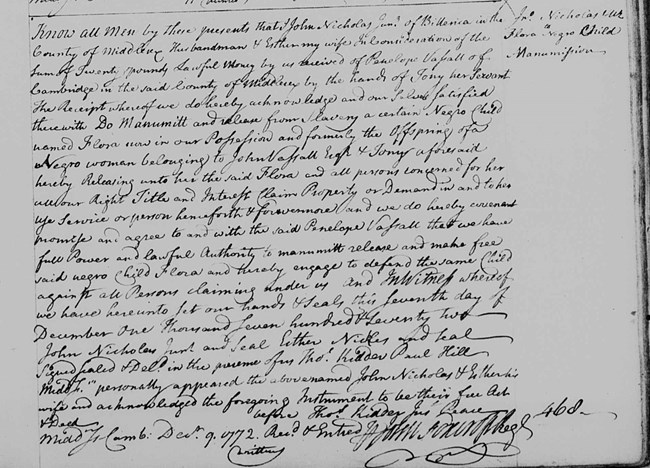

“Jno Nicholas Jun / to / Flora Negro Child / Manumission,” Middlesex County Deeds, Vol 73, page 457. Accessed in "Massachusetts Land Records, 1620-1986." Images. FamilySearch.

Enduring Slavery

Available records reveal a more detailed history of one family enslaved by the white Vassalls. Cuba (later known as Cuba Vassall) was born on Antigua. She and her family – her mother, Abba, and siblings Robin, Walker, Nuba, Trace, and Tobey – were enslaved by Isaac Royall Sr. When Royall moved from Antigua to his estate in Medford (now the Royall House and Slave Quarters Museum) in 1737, he brought at least 27 enslaved people with him, including Abba and her children.7

Two years later, Isaac Royall Sr. bequeathed eight people he enslaved to his daughter:

I give and bequeath unto my well beloved Daughter Penelope , one negro girl called Present and one negro woman called Abba & her six children named Robin Coba [Cuba] Walker Nuba Trace & Tobey to hold to my said Daughter and her Heirs forever.8

In 1742, Penelope married Henry Vassall, John Vassall’s uncle. Upon her marriage, Penelope took Abba, Cuba, and at least some of Cuba’s siblings with her as property to her new home in Cambridge (now 94 Brattle Street). There, Cuba met and married Anthony (often referred to as Tony, including signing his mark as a "T"), a coachman enslaved by Henry Vassall. Oral accounts indicate that Tony Vassall was born in the Spanish Empire around 1713 and kidnapped as a young adult to Jamaica. There, Henry Vassall purchased him.9 When Henry moved to Massachusetts, he brought Tony and several other enslaved people.

According to historian J.L. Bell, enslaved people along the Watertown road likely formed community as they “worked alongside each other in the fields and gardens, shared recipes in the kitchens, and visited from house to house.”10 In 1752, Tony and brother-in-law Robin collaborated with other free and enslaved laborers in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to gain their freedom by taking money from William Brattle and purchasing passage to Canada, then France.11

Tony and Cuba Vassall had at least six children: James (born 1750s), Dorrenda, Flora (born 1767), Darby (born 1769), Cyrus, and Catherine. Their enslavers, however, did not hesitate to separate the family on multiple occasions. In colonial New England, enslaved people were rarely able to live in the same household as their partners, and were frequently separated from their children.12 Around the time of the debt-ridden Henry Vassall’s death in early 1769, he or Penelope sold Cuba to Penelope’s nephew, John. Cuba’s 2-year-old daughter Flora may also have been sold at this time, or earlier. In May 1769, Cuba gave birth to her son Darby. John eventually “gave” a very young Darby to George Reed of Woburn.13

For the next five years, Tony, James, Dorrenda and Cuba remained on Brattle Street, divided among their different enslavers’ households. Their children Flora and Darby were taken further from their family, a cruel and common practice by New England enslavers.14

A record recently identified by the Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery Initiative (pictured above) reveals a less common occurrence. In December 1772, Tony Vassall traveled to the town of Billerica where his young daughter Flora was enslaved. There he delivered a sum of £20 to her enslaver (according to the deed, provided by his enslaver Penelope Vassall) to "manumit release and make free"15 his child. The deed indicated that Flora was released to her still-enslaved mother, Cuba. In this successful act of finding a way to purchase their daughter's legal freedom, Tony and Cuba Vassall began reuniting their family.

Massachusetts Anti-Slavery and Anti-Segregation Petitions; Massachusetts Archives Collection. v.231-Revolution Resolves, 1781. SC1/series 45X. Massachusetts Archives. Boston, Mass.

Seizing Freedom

Increasing unrest and threats of violence, culminating in the Powder Alarm of September 1774, prompted Brattle Street's elite white residents to flee their homes for Boston where they could feel safe with the presence of the British Regulars encamped there.16 John and Elizabeth Vassall and Penelope (Royall) Vassal were among those who fled, leaving behind some of the people they enslaved – including Cuba and Tony (who eventually used the surname Vassall, a complex but common practice). The departure of their enslavers cast their legal status into question. Nonetheless, with their enslavers gone Tony and Cuba Vassall continued to reunite their family in freedom on a portion of the former John Vassall estate.

By July 1775, their six-year-old son Darby had returned following Reed’s death the month prior.17 The paradoxical nature of freedom in the founding era may have been clear to young Darby Vassall – his enslaver died at Bunker Hill, an early battle in the fight for American independence. Historian Gloria McCahon Whiting argues that “Slavery was crumbling in the Bay Colony at precisely the time that Darby decided to go home. At the outbreak of Revolution, people of African descent like Darby, both young and old, simply walked away from their masters’ homes, shops, and farms.”18

During the 1775-1776 Siege of Boston, General George Washington used the John Vassall mansion as his headquarters. Cuba, Tony, and their children remained in another dwelling on the estate, tending three-quarters of an acre for their own livelihood. In a story first recorded after Darby Vassall’s 1861 death, he refused George Washington’s order to work inside the headquarters. While the veracity of the historical encounter is unclear, the narrative power of a formerly enslaved child standing up to the general, himself an enslaver, is clear. In the account, the adult Darby Vassall described George Washington as “no gentleman, he wanted [a] boy to work without wages.”19

Tony and Cuba Vassall spent the next six years living in a small dwelling on the former John Vassall estate, farming three-quarters of an acre for their own livelihood. Tony Vassall supplemented the family’s income with paid work, including work on the confiscated Royall estate in Medford.20 Around 1778, the Middlesex County probate of John Vassall’s former estate reveals an unusual move by Tony Vassall to secure financial stability for his family. Thomas Farrington, a local official overseeing the confiscated Vassall estate, noted that he paid Anthony Vassall the sum of £222 for “supporting a Negro woman & two Children [for] 3 years.”21

According to Whiting, Tony Vassall appears to have made a strategic appeal to Farrington for to the benefit of himself and his family: he asserted that his wife and children "belonged to the Estate of [the] s[ai]d [John] Vassall." As the family continued to live as free people, Whiting argues that “By positioning himself as a free household head and his family members as slaves, Anthony assumed a patriarchal role familiar to the people who held the purse strings of the confiscated Vassall estates.”22

Tony and Cuba Vassall continued to advocate for financial compensation out of their former enslavers’ estate. In 1780, the Massachusetts General Court (the legislature), which had authorized the seizure of properties abandoned by Loyalists, prepared to sell the John Vassall estate to private owners. Tony and Cuba Vassall faced eviction. They petitioned the General Court to be allowed to remain on their small portion of the estate and to continue cultivating an acre of land. The petition again used strategic language, here aimed at persuading the legislators:

The earlier part & vigour of their lives is spent in the service of their several masters, and the misfortunes of war have deprived them of that care & protection which they might otherwise have expected from them—the land Your Petitioners now improve is not sufficient to supply them with such vegetables as are necessary for their family use, and their title is so precarious that they can’t depend on a continued possession of the same— they might however promise themselves a tolerable subsistence by their industry & attention, if this Honble Court would grant them a freehold in the Premises and add one quarter of an acre of adjoining land to that which they now improve.23

That petition was denied. Several months later, in early 1781, they filed a second petition, signed with Tony’s mark:

...though dwelling in a land of freedom, both himself and his wife have spent almost sixty years of their lives in slavery and that though deprived of what makes them now happy beyond expression yet they have ever lived a life of honesty and have been faithful in their master's service…. [One hopes] that they shall not be denied the sweets of freedom the remainder of their days by being reduced to the painful necessity of begging for bread.24

This petition, which invoked post-Revolutionary freedom rhetoric, was successful. Tony Vassall was granted £12 annually.25 The same year, the family was evicted.

Despite the success of their petition, Tony and Cuba Vassall carved out freedom in an environment of ongoing racial discrimination and evolving legal uncertainty. Between 1780-1783, a new state constitution and a series of court cases signaled the legal end of slavery in Massachusetts. Whiting notes that the constitution and courts did not initiate this move toward abolition, but rather took cues from the groundswell of Black legal challenges and flight from slavery leading up to and during the American Revolution.26

In 1787, Tony and Cuba Vassall purchased a home at what is now the corner of Shepard Street and Massachusetts Avenue in Cambridge, and later purchased five additional acres. The national tax valuation from 1798 records Anthony Vassall as owner of five acres of land valued at $290. Tony worked as a paid laborer, yeoman farmer, and farrier. He died at the reported age of 98 on September 2, 1811. That year, Cuba Vassall filed her own successful petition to become the beneficiary of the annual pension.27 Cuba Vassall died the following year on September 16, 1812. Their burial locations are unknown.

Massachusetts Anti-Slavery and Anti-Segregation Petitions; Passed Acts; St. 1861, c.91, SC1/series 229. Massachusetts Archives. Boston, Mass.

Building Community

By 1796, Tony and Cuba’s sons Darby and Cyrus Vassall owned property on May Street (now Revere Street) in Boston. There, they joined an established community of Black Bostonians on the north slope of Beacon Hill. That year, Darby and Cyrus Vassall were among 44 founding members of the benevolent “African Society” in Boston.28 The African Society used monthly dues and the proceeds from a quarterly "Charity Lecture" to support their members during illness and to provide death benefits to their families. In 1807 they took a mortgage to build a “New Brick mansion” on May Street.29 Darby is believed to have worked as a caterer in elite white Boston households.

Darby Vassall married Lucy Holland in 1801 and they had eight children together.30 The baptisms, marriage, and deaths of five of their children were recorded at the Brattle Street Church: William (b. 1803), William (1805-1805), Frances Holland (1806-1885), Sally Campbell (1810-1811), and Richard Chardon (1814-1816).31 They had three other children, Charles Ward and Rhoda Crosby (both baptized at King’s Chapel in 1804) and an unnamed child (1812-1813).32 Their only surviving child, Frances Vassall, married abolitionist Jonas W. Clark in January 1828; Lucy (Holland) Vassall died in December of the same year. Cyrus married Lucy Jenkins and had two children, but died in 1812. The same year, Darby joined activist Primus Hall in a petition for a school for the neighborhood’s Black students, two decades before the construction of the Abiel Smith School.33

Darby and Cyrus Vassall’s sister, Flora, also moved to Boston. She married Bristol Miranday, likely the same man who purchased his own freedom in Westhersfield, CT in 1781.34 Their three children were baptized at King’s Chapel in 1804, several months after her brother Darby baptized two of his children there.35 When Flora Miranday died in March 1815, her daughter Susanna requested that Primus Hall be appointed the administrator of her mother’s will.

Despite the deaths of his parents, several siblings, and most of his children in the first quarter of the 19th century, Darby Vassall persisted in his activism. In 1825, Darby Vassall was the second vice president of an event celebrating the anniversary of Haitian independence, during which he gave the following toast: “Freedom—May the freedom of Hayti be a glorious harbinger of the time when the color of a man shall no longer be a pretext for depriving him of his liberty.”36 He was active in supporting the New England Anti-Slavery Society, and was a guest of honor at an 1858 abolitionist commemoration of the Boston Massacre.37 In 1861, with his daughter Frances and son-in-law Jonas Clark (who he lived with for much of his later life), 92-year-old Darby Vassall signed a petition aimed at protecting the Black community against the Fugitive Slave Act.

On the morning of March 22, 1855, the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, now occupying the former John Vassall house at 105 Brattle Street, recorded a visit from 86-year-old Darby Vassall in his journal:

[Publisher James] Fields comes out to hear some part of “Hiawatha.” Read to him the Introduction and “The Peace Pipe.” Then we are interrupted. Lundy Lane and old Mr. Vassall (born a slave in this house in 1769) come to see me, and stay so long that Fields is driven away, and there is no end of the reading.38

Despite Longfellow’s brevity, his meeting with the lifelong activist who had begun his life enslaved in the home where they now conversed was a historic encounter. Two days later, Longfellow recorded a $10 donation to Darby Vassall.39

Darby Vassall died on October 12, 1861, at the age of 92. He chose to be buried in the tomb of the Henry Vassall family under Christ Church in Cambridge, receiving permission in 1843 from Catherine Graves Russell, the granddaughter of the man who had enslaved his parents.40 A notable obituary was written by the renowned activist William Cooper Nell (who had also boarded with Darby Vassall’s son-in-law several years earlier41) and published in The Liberator. Nell wrote of Vassall:

He had an intelligent appreciation of the Anti-Slavery movement, and loved to speak with and of Wm. Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips…Mr. Vassall was favored with a wonderful memory, and it was deemed a privilege with many persons, from different walks in life, to avail themselves of his conversational reminiscences of Boston and vicinity, in the olden time.42

Darby Vassall's siblings and descendants shaped their communities as well. In 1815, his sister Catherine Vassall married Adam Lewis, first living in the house that her parents had purchased. They sold that house the following year,43 and in 1819 purchased a triangular lot in Cambridge on the corner of Garden Street and Concord Street near the Cambridge Common.44 This family formed the nucleus of a burgeoning Black community in Cambridge known as “Lewisville” after the many Lewis family members who lived there or had ties there.

Many of the Lewis family members were active in the abolition and civil rights movements. In 1826, Adam Lewis’s brother, (Quaku or Quork) Walker Lewis, was a founding member of the Massachusetts General Colored Association, which later merged with the New England Anti-Slavery Society.

After passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, people of African descent were at risk of being claimed as escaped slaves with little legal recourse. Many African Americans fled the country to safer territory in Canada or joined the movement to create new communities in places such as Liberia. In 1858, another Lewis brother, Enoch, formed the Cambridge Liberian Emigrant Association.45 The Association solicited contributions; in October 1858, the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow recorded donating $10.00 for “Negroes to Liberia.”46

In November of that year, twenty-three Black Cambridge residents (many of them Lewis family members) joined a larger group that sailed for Liberia.47 Their intention was to “better the condition of ourselves and our posterity.”48 At this time, not much is known about what happened to the group after they reached Liberia. The departure of the Cambridge Liberian Emigrant Association significantly reduced the population of the Lewisville community. As the Lewisville community dispersed, so too did much of its public memory – although descendants of the original Lewis family remained in the area up through the 1970s.

Today, the legacy of these families who endured slavery and fought for freedom in Cambridge persists. Learn more about the history of slavery at 105 Brattle Street here. Visit the Cambridge Black History Project and History Cambridge for more local history and community.

Recommended Resources

Grover, Kathryn and Janine V. da Silva. Historic Resource Study: Boston African American National Historic Site. National Park Service. 2002. https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/0a7483f1-1396-4790-8ab0-f537dbb648d5/original?

Hardesty, Jared Ross. Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds: A History of Slavery in New England. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2019.

“Report of the Presidential Committee on Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery.” Harvard University. 2022. (See especially Chapter III) https://legacyofslavery.harvard.edu/report/financial-ties-harvard-and-the-slavery-economy

Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site. “Research Guide to Black History in the Longfellow Archives.” 2022. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/research-guide-to-black-history-in-the-longfellow-archives.htm

Kidder, David. “Owning Our History: First Church and Race 1636-1873.” First Church Cambridge, 2013, revised 2019. https://www.firstchurchcambridge.org/owning-our-history/

Maycock, Susan E. and Charles Sullivan. Building Old Cambridge: Architecture and Development. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2016.

Museum of African American History and Boston African American National Historic Site. “Smith Court Stories.” 2020. https://smithcourtstories.org/commemorations-at-smith-court/

Museum of African American History and Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery. “We Claim/Reclaim Space: Darby Vassall's Life and Legacy.” Online exhibit. 2022. https://www.weclaimspace.org/

Nell, William Cooper. The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution: With Sketches of Several Distinguished Colored Persons Boston: Robert R. Wallcut, 1855.

Piepenbrink, Nicole Catherine. “Here Lies Darby Vassall: Rendering the obscured and concealed history of slavery at Christ Church Cambridge.” Cambridge, MA: Harvard Graduate School of Design. 2022.

https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/37372350 (See also project website: https://hereliesdarbyvassall.art/)

Royall House and Slave Quarters. "Belinda Sutton and Her Petitions." https://royallhouse.org/slavery/belinda-sutton-and-her-petitions/

University College London. “Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery.” https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs (Includes records on John Vassall (father and son), Leonard Vassall, the Newfound River plantation in Hanover, Jamaica, and the Vassall-Craigie-Longfellow House)

Whiting, Gloria. "Endearing Ties": Black Family Life in Early New England. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. 2016. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493445

Notes

1 Susan E. Maycock and Charles M. Sullivan, Building Old Cambridge (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2016), 193.

2 “John Vassall II,” Legacies of British Slavery Database. Accessed January 12, 2023. http://wwwdepts-live.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146634272.

3 Jared Ross Hardesty. Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds: A History of Slavery in New England. (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2019), xvi.

4 Hardesty, xv.

5 Maycock and Sullivan, 20.

6 Ibid.

7 "The Royalls." Royall House and Slave Quarters. Accessed January 12, 2023. https://royallhouse.org/the-royalls/.

8 Will of Isaac Royall Senior, Middlesex Country Probate Court Records No. 19535. Accessed at https://royallhouse.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/PrimarySources_public_records.pdf. Middlesex Probate 19545

9 Samuel Francis Bachelder. Notes on Colonel Henry Vassall (1721-1769): His Wife Penelope Royall, His House at Cambridge, and His Slaves Tony & Darby. (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1917), 62. Accessed at https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=nJYlAQAAMAAJ.

10 Bell, 35.

11 Hardesty, 114-115.

12 Whiting, 268.

13 Bell, 38.

14 For a discussion of the deep trauma of family separation, and Tony and Cuba Vassall’s possible efforts to retain some control, see Whiting 268-270.

15 "Jno Nicholas Jun / to / Flora Negro Child / Manumission,” Middlesex County Deeds, Vol 73, page 457. Accessed in "Massachusetts Land Records, 1620-1986." Images. FamilySearch. http://FamilySearch.org : 18 July 2022. County courthouses and offices, Massachusetts.

16 Bell, 16.

17 Bell, 39.

18 Whiting, 274.

19 The New England Historical and Genealogical Register: Volume 25 (1871), 44-45.

20 Bachelder, 69.

21 Middlesex Country Probate Court Records No. 23340

22 Whiting, 290.

23 Digital Archive of Massachusetts Anti-Slavery and Anti-Segregation Petitions, Massachusetts Archives, Boston MA, 2015, "Massachusetts Archives Collection. v.186-Revolution Petitions, 1779-1780. SC1/series 45X, Petition of Anthony Vassall", https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/I3QTHU, Harvard Dataverse, V5.

24 Digital Archive of Massachusetts Anti-Slavery and Anti-Segregation Petitions, Massachusetts Archives, Boston MA, 2015, "Massachusetts Archives Collection. v.231-Revolution Resolves, 1781. SC1/series 45X, Petition of Anthony Vassall", https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QIHQT, Harvard Dataverse, V5.

25 Whiting, 293.

26 Whiting, 274.

27 Digital Archive of Massachusetts Anti-Slavery and Anti-Segregation Petitions, Massachusetts Archives, Boston MA, 2015, "Passed Resolves; Resolves 1811, c.154, SC1/series 228, Petition of Cuby Vassall", https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/UVLNE, Harvard Dataverse, V5.

28 “Laws of the African Society, Instituted at Boston, Anno Domini 1796,” Massachusetts Historical Society Collections Online. https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=573&pid=42

29 Batchelder, 75. Not borne out in Suffolk deed records – Cyrus’s mortgage is 1801.

30 Bell, 39.

31 Church in Brattle Square (Boston, Mass.), The Manifesto church. : Records of the church in Brattle square, Boston, with lists of communicants, baptisms, marriages and funerals, 1699-1872. 1902. https://archive.org/details/manifestochurchr00chur_0. The births of both Williams, “Francis Son” [sic], Sally Campbell, and Richard Chardon are also recorded in Boston Town Records, formally titled Reports of the Record Commissioners of the City of Boston. Boston: Rockwell & Churchill, 1876-1905. Vol. 24, p. 352-355. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112038101942&view=1up&seq=362

32 King’s Chapel Register of Baptisms, reproduced in “Uncovering the Past: Exploring Black History through Primary Sources.” http://www.kings-chapel.org/uncover12.html

33 Digital Archive of Massachusetts Anti-Slavery and Anti-Segregation Petitions, Massachusetts Archives, Boston MA, 2015, "Senate Unpassed Legislation 1812, Docket 4522, SC1/series 231, Petition of Primus Hall", https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RI3NT, Harvard Dataverse, V4

34 Black History in Wethersfield,” Wethersfield Historical Society. https://www.wethersfieldhistory.org/articles/black-history-in-wethersfield/.

35 “Flora Miranday & Family,” Uncovering the Past: Exploring Black History through Primary Sources, King’s Chapel. Accessed January 12, 2023. http://www.kings-chapel.org/uncover11.html

36 Bell, 40.

37 ”The Boston Massacre, March 5, 1770, Commemorative Festival in Faneuil Hall,” The Liberator, March 12, 1858, Digital Commonwealth, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/5h742g15b.

38 Journal of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 22 March 1855. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

39 Listed under heading “Money given 1855,” p. 179. Volume in the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University (MS Am 1340 (152). http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn‐3:FHCL.HOUGH:1476983

40 Bell, 41.

41 Kathryn Grover and Janine V. Da Silva, "Historic Resource Study: Boston African American National Historic Site," Boston African American National Historic Site, 2002, 65. https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/0a7483f1-1396-4790-8ab0-f537dbb648d5

42 "Darby Vassall," The Liberator, November 22 12, 1861, Digital Commonwealth, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/mc87rg189.

43 Maycock and Sullivan, 281.

44 Maycock and Sullivan, 264.

45 "Walker Lewis (1798 – 1856)." Untold Lowell Stories: Black History, University of Massachusetts Lowell Library. https://libguides.uml.edu/c.php?g=1125577&p=8217665

46 Listed under heading “1858,” p. 148. Volume in the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University (MS Am 1340 (152). http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn‐3:FHCL.HOUGH:1476983

47 Maycock and Sullivan 67.

48 “Emigration to Liberia,” The Cambridge Chronicle, Volume XIII, Number 28, July 10, 1858, Cambridge Public Library's Historic Cambridge Newspaper Collection, https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/?a=d&d=Chronicle18580710-01.2.8&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-------.