Last updated: January 8, 2026

Article

Primus Hall: A Revolutionary Life of Service

Born in Boston to enslaved parents of African descent, Primus Hall would also be considered enslaved himself. However, when sent away to live with the Trask family in the countryside town of Danvers, Massachusetts, Primus grew up as an indentured apprentice and personally rejected the enslaved status given to him upon birth. As he came of age, nearing 20 years old, Primus Hall first enlisted to serve in the American Revolutionary War in January 1776. This decision led to a lengthy military career that took him to various states along the east coast, including New York, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Virginia.

Upon his return to Boston, Hall earned enough money through his soap-boiling business to accumulate land in Beacon Hill and firmly established himself and his family in the neighborhood. His veteran's status and leadership skills gained him a respectable reputation and he channeled these skills and influence into community activism. He dedicated his later years to advocating for equal educational opportunities for Black children and became known as a "patriarch" of the Black community in Boston. Additionally, stories of his presumed personal relationships with prominent war figures, including George Washington and Timothy Pickering, elevated his credibility and became powerful tools in the community's fight against slavery and racism.

Hall’s story serves as an inspiring and unique bridge between the brave Revolutionary War service of Black soldiers and the post-war abolition movement in Boston.

Explore the story map below to learn about Primus Hall’s life story. Click "Get Started" to enter the map. To read more about each point, click "More" or scroll to view the map, historical images, and accompanying text. To navigate between the points, please use the "Next Stop" button at the bottom of the slides or the arrows on either side of the main image. To view a larger version of the main image depicted below the map, click on the image.

Footnotes:

[1] This is not to be confused with the radical abolitionist David Walker who published his famous “Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World” in 1829.

[2] Arthur O. White, “The Black Leadership Class and Education in Antebellum Boston,” The Journal of Negro Education 42 no. 42 (Autumn 1973): 504. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2966563.

[3] Jeremy Belknap, “Queries respecting slavery in Massachusetts with answers (manuscript draft),” Massachusetts Historical Society Collections Online (April 1795): 14. https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=684&mode=transcript&img_step=15#page15.

[4] “Binding Out,” Primary Research, https://primaryresearch.org/binding-out/.

[5] Primus Hall, Pension No. W. 751, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 75, via Fold3.com.

[6] Primus Hall, Pension No. W. 751, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 35, via Fold3.com.

[7] Jared Ross Hardesty, Unfreedom: Slavery and Dependence in Eighteenth Century Boston (New York: New York University Press, 2018), 2.

[8] Primus Hall, Pension No. W. 751, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 5, via Fold3.com.

[9] Richard Frothingham, History of the Siege of Boston (Boston: Charles C. Little and J. Brown, 1851), 411. Archive.org.

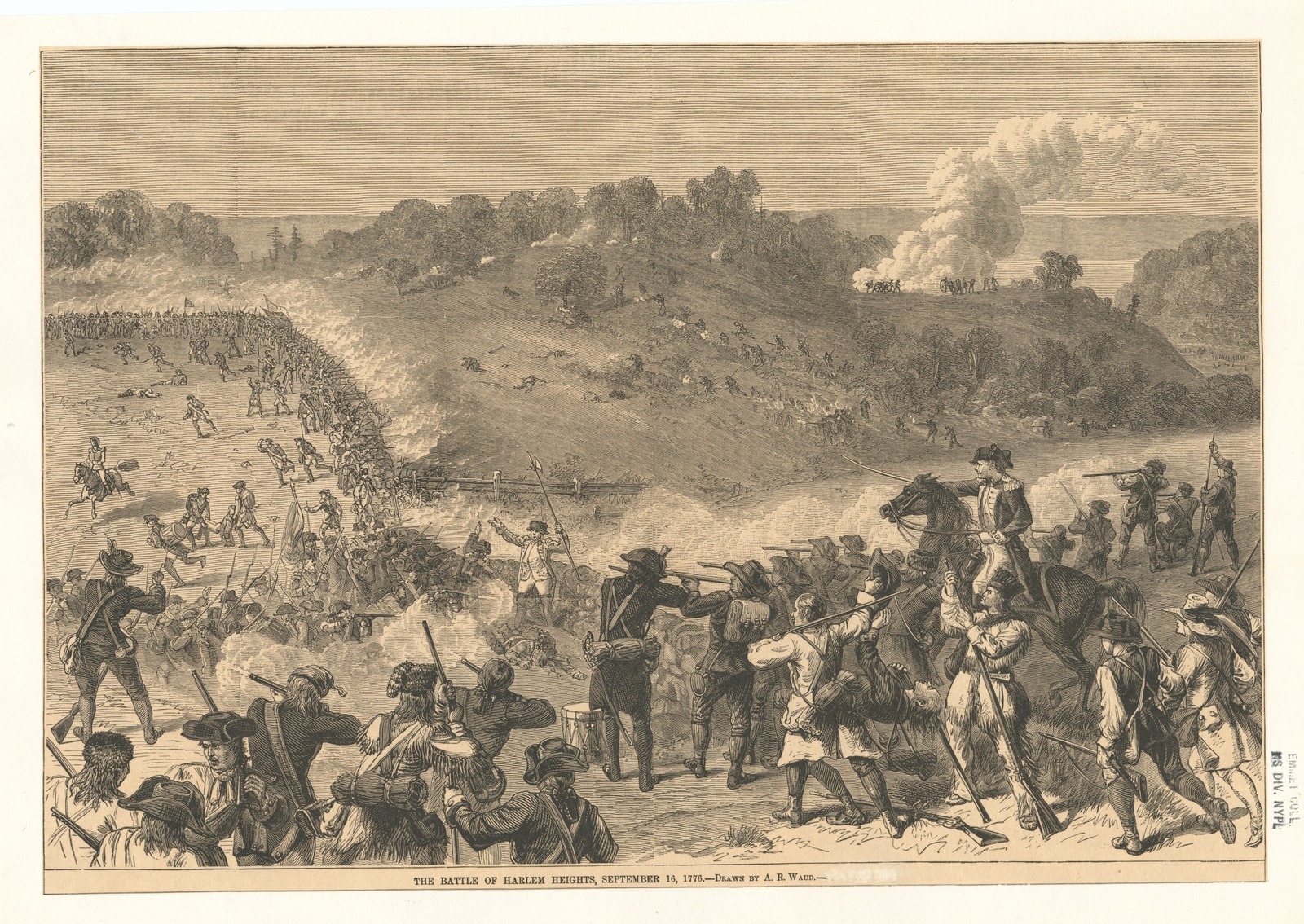

[10] Harry Schenawolf, “Battle of Harlem Heights Sept. 16, 1776: Americans Gave the British a Good Drubbing,” Revolutionary War Journal, January 15, 2014. https://www.revolutionarywarjournal.com/battle-of-harlem-heights/.

[11] David G. McCullough, 1776 (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2006), 219. Archive.org.

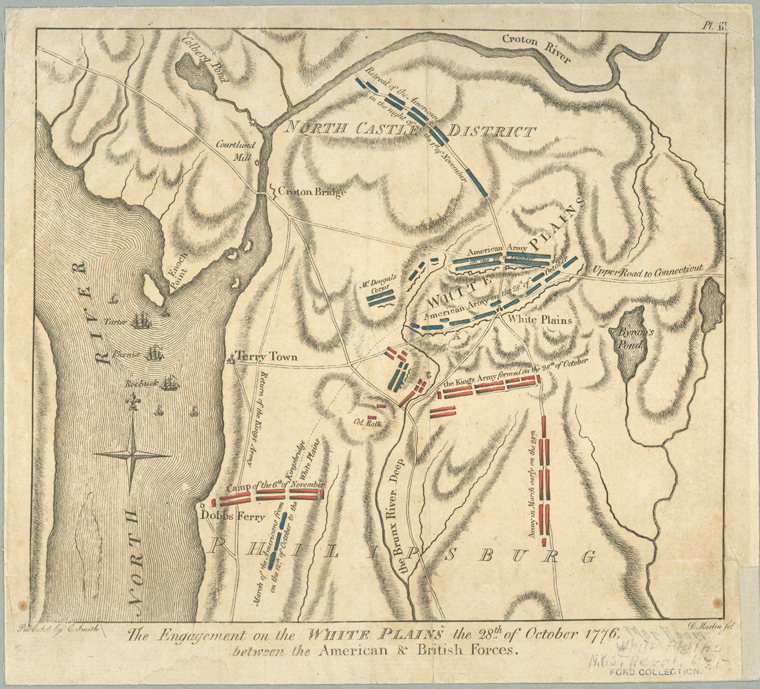

[12] McCullough, 1776, 232-234. Joseph C. Scott, “Battle of White Plains,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/battle-of-white-plains/.

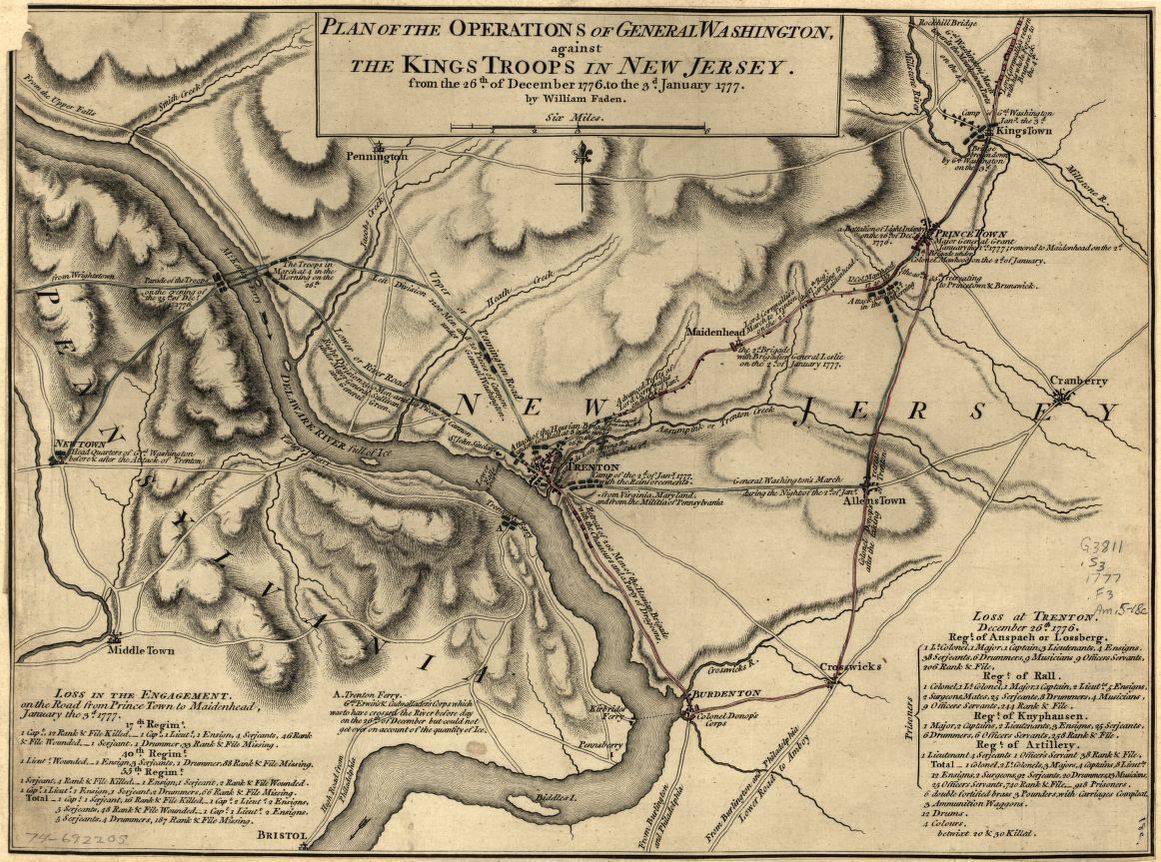

[13] David Hackett Fischer, Washington’s Crossing (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 208-209.

[14] Colonel Hitchcock’s New England soldiers joined Colonel John Cadwalader’s Philadelphia troops for this mission. “From George Washington to Colonel John Cadwalader, 25 December 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-07-02-0343.

[15] “To George Washington from Colonel John Cadwalader, 26 December 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-07-02-0347.

[16] Fischer, Washington’s Crossing, 272-3.

[17] Primus Hall, Pension No. W. 751, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 6, via Fold3.com.

[18] Fischer, Washington’s Crossing, 307.

[19] McCullough, 1776, 288-290.

[20] Pay Roll of Capt. Samuel Flint’s Company of Massachusetts Bay Militia, Muster/Payrolls and Various Papers (1763-1808) of the Revolutionary War, Vol. 19, Image 153, 1777, via FamilySearch.org.

[21] Primus Hall, Pension No. W. 751, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 7, via Fold3.com.

[22] Troy Smith, “Battle of Saratoga,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/battle-of-saratoga/.

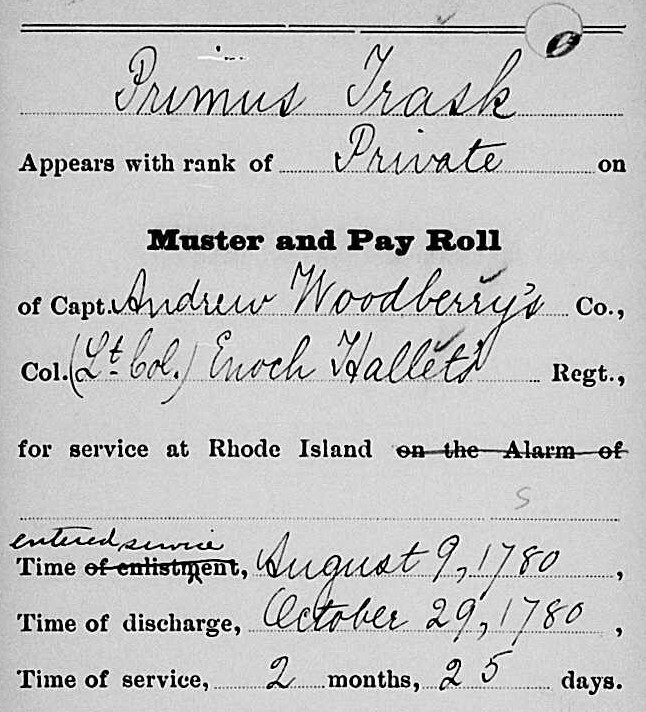

[23] Primas Trask, Massachusetts, Revolutionary War, Index Cards to Muster Rolls, 1775-1783, Tower, Peter-Trescott, John, Image 2139, via FamilySearch.org.

[24] In his pension application, Hall stated that he marched to Rhode Island in 1778, but muster rolls confirm that he had been there in the fall of 1780. Pay Roll of Capt. Andrew Woodberry’s Company of Militia, Muster/Payrolls and Various Papers (1763-1808) of the Revolutionary War, Vol. 3, Image 408, July 1780, via FamilySearch.org.

[25] Primus Hall, Pension No. W. 751, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 7, via Fold3.com.

[26] Primus Hall, Pension No. W. 751, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 7, via Fold3.com.

[27] A specie is a form of coined money. Primus Hall, Pension No. W. 751, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 8, via Fold3.com.

[28] “1785 additional and abatement books,” City of Boston Tax Records, 1780-1821, reel 1 (1780-1786), p. 608, Boston Public Library. Archive.org.

[29] Primus Hall, Pension No. W. 751, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 13, via Fold3.com.

[30] Primus Hall, Pension No. W. 751, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 38, via Fold3.com.

[31] “Primus Trock Hall,” Massachusetts, U.S., Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988, via Ancestry.com. Births, marriages, deaths 1635-1844, Hingham, Plymouth, Massachusetts, Town Clerk, Vital and Town Records, 1626-2001, Image 301, via FamilySearch.org.

[32] “Deaths,” Columbian Centinal, December 21, 1808, via GenealogyBank.com.

[33] “Primus Hall,” Massachusetts, U.S., Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988, via Ancestry.com.

[34] “Deaths,” Boston Patriot, January 22, 1817, via GenealogyBank.com.

[35] Though we could not find any birth certificates for the children, we did find death notices connecting Primus Hall to at least three of the children. The children are believed to be as follows:

- Phebe Ann Clark, died June 1, 1821, age 3

- George P. Hall, died June 7, 1825, age 4

- Peter, died December 24, 1829, age 1

- Ezra T. Hall, died February 5, 1843, age 18

- Hannah Hall, died February 26, 1850, age 19

Births, Marriages and Death, Massachusetts, U.S., Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988, via Ancestry.com.

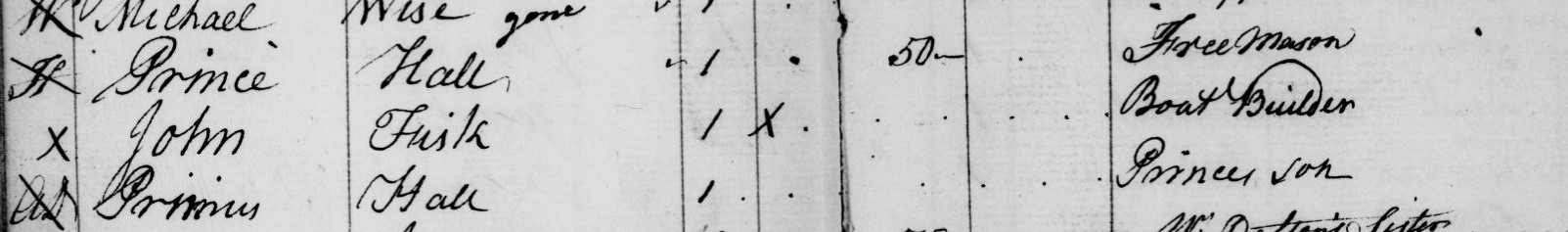

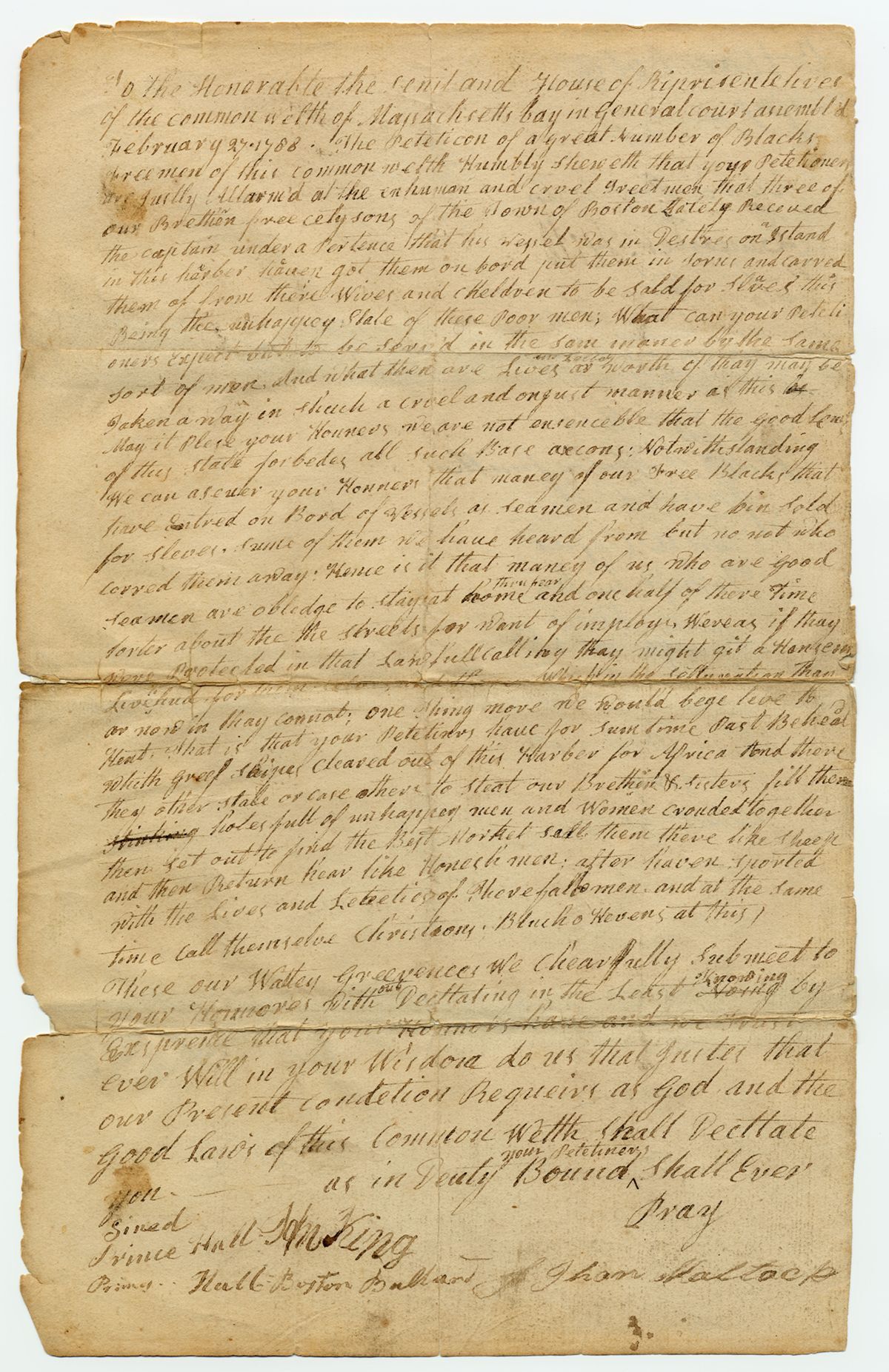

[36] “Documents Relating to Negro Masonry in America.” The Journal of Negro History 21 no. 4 (Oct. 1936): 428-9. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2714334.

[37] “Bobolition of Slavery!!!!” Broadside, Greenfield, Mass: unidentifed printer, 1818, https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=3201&pid=3.

[38] The Liberator, July 14, 1832, via GenealogyBank.com.

[39] James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton, Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (New York: Holmes & Meier, 1999), 76. Archive.org.

[40] Ibid, 77.

[41] George A. Levesque, “Before Integration: The Forgotten Years of Jim Crow Education in Boston,” The Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 48, no. 2 (Spring, 1979): 115. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2294758. Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 127.

[42] "Though Dwelling in a Land of Freedom,” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/though-dwelling-in-a-land-of-freedom.htm.

[43] Kathryn Grover and Janine V. da Silva, “Historic Resource Study: Boston African American National Historic Site,” National Park Service (Dec. 31, 2002).

[44] Records show Primus Hall buried at Saint Matthews Church Cemetery. The church and cemetery closed in the 1860s and the bodies moved to another cemetery. It appears that many of the bodies were re-interred at Mount Hope Cemetery. “Primus Hall,” Massachusetts, U.S., Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988, via Ancestry.com. “Boston, Suffolk County, Massachusetts Genealogy,” FamilySearch, via FamilySearch.org.

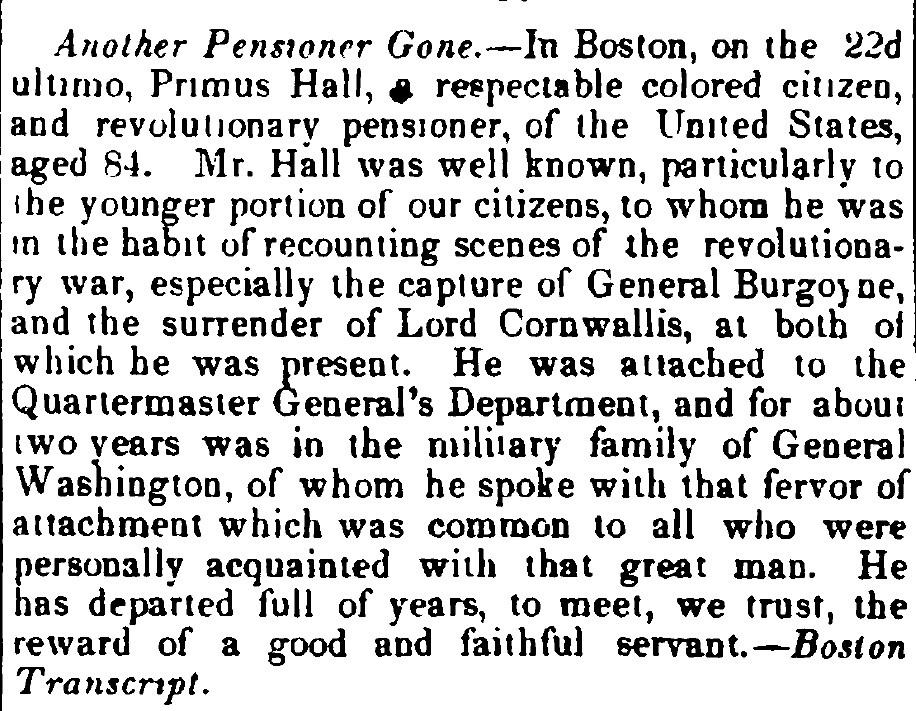

[45] The Boston Transcript via The Liberator, April 8, 1842, via Newspapers.com.

[46] Finkelman, Dred Scott v. Sandford. Bedford: St. Martin's Press, 1997, reproduced by PBS.org.

[47] William Cooper Nell, The Liberator, August 28, 1857. Cited in William Cooper Nell: Selected Writings 1832-1874, ed. Dorothy Porter Wesley and Constance Porter Uzelac (Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 2002), 493.

[48] Nell cited another source for this anecdote. We have yet to discover a primary source confirming that Primus Hall himself shared this story. William Cooper Nell, The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution: With Sketches of Several Distinguished Colored Soldiers (Boston: Robert F. Wallcut, 1855), 29. Archive.org.

[49] Commercial Bulletin, January 12, 1867, via Newspapers.com.