Last updated: January 21, 2025

Article

NPS Geodiversity Atlas—El Morro National Monument, New Mexico

Geodiversity refers to the full variety of natural geologic (rocks, minerals, sediments, fossils, landforms, and physical processes) and soil resources and processes that occur in the park. A product of the Geologic Resources Inventory, the NPS Geodiversity Atlas delivers information in support of education, Geoconservation, and integrated management of living (biotic) and non-living (abiotic) components of the ecosystem.

Introduction

El Morro National Monument preserves and protects Inscription Rock and its inscriptions and petroglyphs that were made over a period of nearly 1,000 years, as well as ancestral Puebloan archeological sites located on top of the El Morro bluff.

El Morro was established on December 8, 1906. It was the second national monument established using the Antiquities Act, and the first to preserve cultural resources.

Geologic Significance & Geodiversity Highlights

Photo by Allyson Mathis.

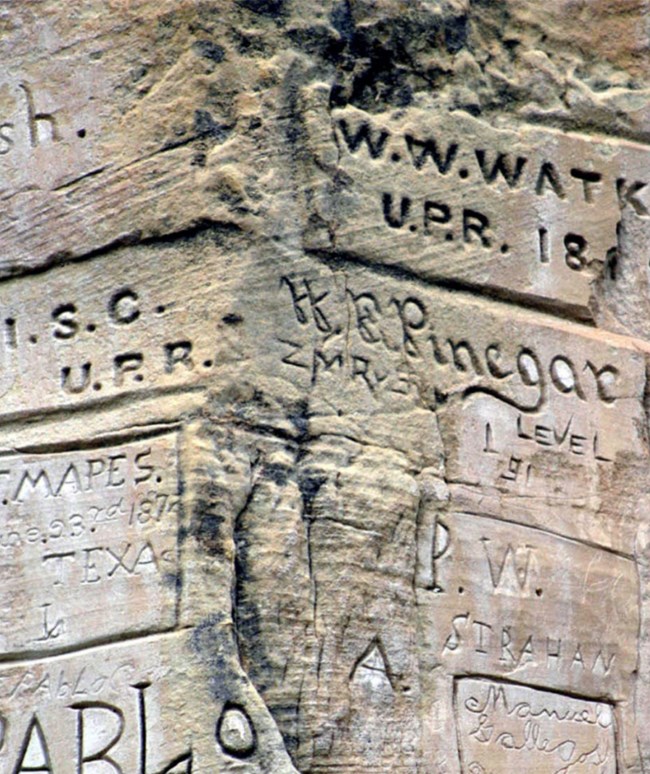

El Morro National Monument’s geologic resources are integral to the cultural significances that led to its protection as a national monument. Although geology impacts the human history everywhere, the approximately 2,000 inscriptions, petroglyphs and pictographs on Inscription Rock are directly on geologic features, leading to an unusually close interplay and interrelationship between cultural resources and geologic resources.

Inscription Rock and the El Morro bluff are made of the Zuni Sandstone. The eolian Zuni Sandstone was deposited in a desert sand dune environment during the Middle Jurassic period, approximately 165 million years ago.

Inscription Rock is located on the northern erosional scarp of a cuesta held up by the resistant Dakota Sandstone which overlies the Zuni Sandstone. The regional dip is a few degrees to the southwest. A cuesta is an asymmetric ridge with a gentle dip slope on one side and a steep to cliff-like face on the other side.

El Morro (“the headland”) was an important landmark for ancestral Puebloan people, Spanish explorers and settlers, and a variety of European American travelers. The permanent pool at the base of Inscription Rock was a key important water source for the ancestral Puebloans living in the area and to people traveling overland from the Spanish period until the completion of the transcontinental railway through a pass north of El Morro in 1881.

Geologic Setting

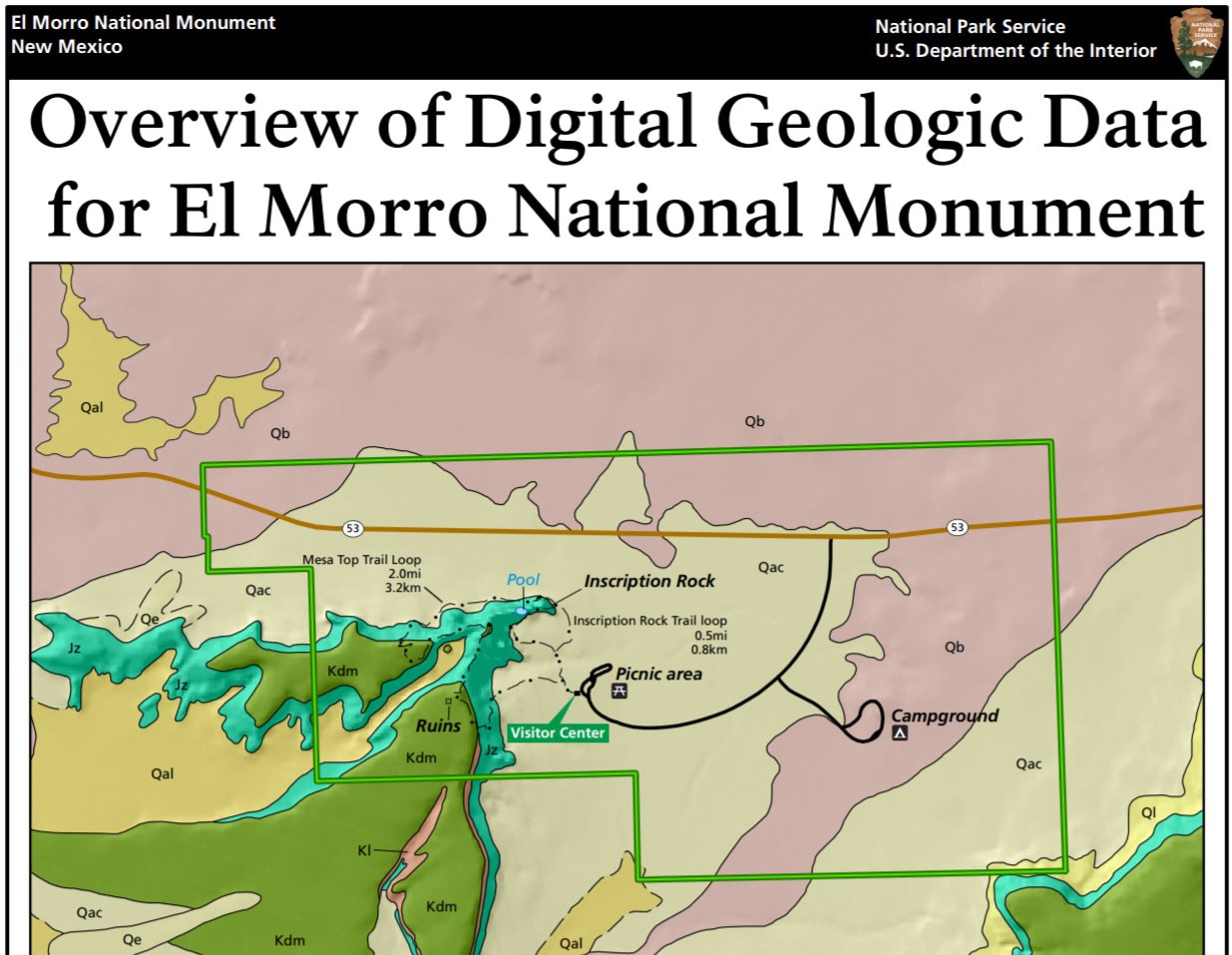

Graphic by Philip Reiker (NPS Geologic Resources Division).

El Morro National Monument is located near the southern margin of the Colorado Plateau, one of 25 physiographic provinces in the contiguous United States. The Colorado Plateau has an overall high elevation, thick continental crust, and has experienced relatively little structural deformation.

El Morro National Monument also lies along the southern flank of the Zuni Uplift where a belt of Jurassic and Cretaceous sedimentary rocks are exposed. The Zuni Mountains formed during the Laramide Orogeny between about 75 and 50 million years ago.

The monument is also near the western extent of the Zuni-Bandera Volcanic Field. The Zuni-Bandera Volcanic Field is a monogenetic volcanic field consisting of lava flows and their vents which include numerous cinder cones. The Zuni-Bandera Volcanic Field has been active during the last 700,000 years. El Malpais National Monument, which is about 40 miles (65 km) east of El Morro, was established to preserve the rugged volcanic terrain formed by the more recent activity of this field.

Geologic History

Rocks exposed in and around El Morro National Monument range in age from the Jurassic Zuni Sandstone to Pleistocene lava flows erupted in the Zuni Bandera Volcanic Field.

The El Morro bluff is an erosional feature formed as a part of the overall degradation of the Colorado Plateau during the Late Cenozoic.

Zuni Sandstone

NPS photo.

Most of the 200-foot (60-m) height of the El Morro bluff consists of the eolian Zuni Sandstone. The Zuni Sandstone is fine-grained and has large crossbedding indicative of its depositional environment in sand dunes. It is found in western New Mexico south of I-40 and correlates with the Entrada Sandstone to the north.

The Zuni Sandstone is extremely friable because it is cemented mostly by clay minerals (with lesser amounts of calcite and iron oxide). It is even more friable than the other friable sandstones on the Colorado Plateau like the Navajo and Entrada sandstones that predominately have calcite cement.

The softness of the Zuni Sandstone helped make Inscription Rock an ideal canvass for people to carve petroglyphs and inscriptions through the centuries.

Dakota Sandstone

In El Morro National Monument, the Dakota Sandstone consists of a lower cross-bedded sandstone with conglomerate lenses and an overlying section of gray mudstone and shale. The lower contact with the Zuni Sandstone contains blocks of reworked Zuni Sandstone. The Dakota Sandstone typically records the transgressive sequence of the Western Interior Seaway.

The pueblos on top of the El Morro bluff were built on the mudstone and shale units. The Dakota Sandstone is quite thin in monument, being only up to 50 feet (15 m) thick.

Old Basalts of the Zuni-Bandera Volcanic Field

Graphic by Jason Kenworthy, NPS Geologic Resources Division.

The youngest rock unit in El Morro National Monument is a basaltic lava flow erupted from the Zuni-Bandera Volcanic Field. The flow is weathered and largely covered by soil, alluvium, or eolian deposits. Lava flows erupted from vents in the volcanic field traveled great distances down river valleys and in topographic lows to the El Morro area.

The lava flow exposed in El Morro National Monument was erupted during the first phase of activity in Zuni-Bandera field. The three phases of activity in the Zuni-Bandera Volcanic Field are:

- Old Basalt Flows Phase: Volcanism began approximately 700,000 years ago with the eruptions of the old basalt flows. These lava flows are deeply weathered and largely covered by soil or alluvium.

- Chain of Craters Phase: This phase occurred mostly west of El Malpais National Monument approximately 150,000 years ago.

- El Malpais Phase: The most recent phase of activity took place from 60,000 to 3,900 years with the eruption of five main lava flows in El Malpais National Monument from a series of vents including cinder cones and a low shield volcano.

Geologic Features and Processes

Inscription Rock and the El Morro Bluff

NPS photo.

Inscription Rock is an approximately 0.3-mile (0.5-km) section of the El Morro bluff near the Historic Pool where most of the inscriptions, petroglyphs, and pictographs i are found. Inscription Rock is an open air record of at least a thousand years of human history with inscriptions, petroglyphs, and pictographs made by ancestral Puebloans, Spanish explorers, and surveyors, pioneers, military expeditions through the 1800s.

The soft Zuni Sandstone is extremely friable. This rock unit readily undergoes granular disintegration which helped make it an easily carved medium for making petroglyphs and inscriptions. Inscribers were able to form crisp edges that lasted for periods ranging from decades to centuries. Some inscribers even prepared the rock surface by smoothing it and rubbing off loose grains.

However, the friable nature of the Zuni Sandstone also makes the inscriptions and petroglyphs of Inscription Rock susceptible to inevitable loss via erosion and weathering. Significant processes include rockfall, exfoliation, granular disintegration, and alveolar erosion. While these processes may occur at any time, they are more likely, more active, and/or more rapid during wet conditions, either from rainfall or melting snow, or when wetting and drying cycles are occurring.

The loss of inscriptions is a significant concern at El Morro National Monument. The weathering and erosion of Inscription Rock is complex due to variations in the cementation and permeability of the Zuni Sandstone, the presence of joints, the presence or absence of rock varnish, slope aspect, and other factors. Inscriptions may be lost due to rockfall or slab failure or localized processes including granular disintegration and lichen growth or boring by insects.

Rockfall is a major mechanism in the escarpment retreat of El Morro. The rate of escarpment retreat is unknown but is likely to be rapid given the poorly indurated nature of the Zuni Sandstone.

Joints

Graphic by Jason Kenworthy, NPS Geologic Resources Division.

The primary joint system in the Zuni Sandstone of El Morro bluff has an east-northeast trend. The face of part of Inscription Rock follows the approximate trend of this vertical joint set. A second joint set intersects the primary one at approximately right angles.

Erosion along these fracture systems plays an important role in the geomorphology of El Morro and its continued weathering and erosion by providing areas of increased permeability and planar surfaces where rockfalls may be initiated.

Tafoni

Photo by Allyson Mathis.

Alveolar erosion (salt weathering) produces a honeycomb pattern evident on areas of Inscription Rock. These openings are also known as tafoni and are fairly common on sandstone surfaces throughout the Colorado Plateau.

Alveolar erosion is a physical disintegration process caused by the repeated wetting and drying cycles that cause the dissolution, precipitation, and expansion of naturally occurring salts (including calcium carbonate, gypsum and other minerals). Once depressions begin to form on a rock surface, they usually deep through differential erosion and positive feedback loops.

Alveolar erosion of the Zuni Sandstone in El Morro National Monument seems to be controlled by both environmental factors and its internal stratigraphy.

Salt weathering is one of the most common factors in deterioration of petroglyphs and pictographs on Inscription Rock.

Desert Varnish

Photo by Allyson Mathis.

Many of the Zuni Sandstone surfaces on Inscription Rock and the El Morro bluff are coated with a variety of thin rock coatings collectively known as desert varnish. Desert varnish consists of rock varnish, heavy metal (iron and manganese) skins, silica glaze, and other components. It may preferentially form where water streaks down cliff faces.

Historic Pool and Geohydrology

Right: Photo by Allyson Mathis.

The Historic Pool at the base of Inscription Rock is an essential part of the human story of El Morro and Inscription Rock. It is the only permanent water source in El Morro National Monument and is also an important water source for wildlife. It served as a water source for the Puebloan people living in the area (including at Atsinni on top of the bluff) and was a key water stop on the overland travel route used from the Spanish period until the late 1800s.

The Historic Pool was dammed by the National Park Service in the 1920s, but human alteration to the pool clearly predated this modification as structures were uncovered during construction. This dam was destroyed by a rockfall in 1942, and was a new dam raised the level of the pool by 13 feet (4 m), greatly enlarging it.

The Historic Pool is fed by runoff from the El Morro bluff as well as some contribution from shallow perched aquifers that sometimes are present nearby.

Tinajas

Tinajas (Spanish for “bowl” or “jar”) are natural depressions on bedrock surfaces that hold rainwater or snowmelt. They are found on top of Zuni Sandstone and Dakota Sandstone surfaces in El Morro National Monument. They were used as water sources for the ancestral Puebloan people who lived in the area. They are also important to wildlife and host specially adapted organisms including fairy shrimp.

Box Canyon

Box Canyon is a small canyon eroded into the Zuni Sandstone in the southwestern part of El Morro National Monument. It has vertical walls and is oriented to the east-northeast like the dominant joint set in the monument, indicating that erosional along joints most likely played a role in its development.

Groundwater sapping is a major erosional process in the formation of box canyons. Headward erosion occurs as a result of groundwater emergence on a cliff face spalling and alcove development.

Paleontological Resources

There are no known paleontological resources in El Morro National Monument, although it is possible that fossils may be found in the sedimentary units. Fossils are more likely to be found in the Dakota Sandstone than the Zuni Sandstone since the Zuni Sandstone is generally very fossil poor.

All NPS fossil resources are protected under the Paleontological Resources Preservation Act of 2009 (Public Law 111-11, Title VI, Subtitle D; 16 U.S.C. §§ 470aaa - 470aaa-11).

Caves and Karst

El Morro National Monument has not been identified by the National Park Service as having either karst or pseudokarst.

Related Links

- NCKRI—Evaluation of Cave and Karst Programs and Issues at US National Parks [PDF]

- All NPS cave resources are protected under the Federal Cave Resources Protection Act of 1988 (FCRPA)(16 U.S.C. § 4301 et seq.).

Geohazards

The primary geohazards in El Morro National Monument range are associated with rockfall and hillslope processes.

Rockfall and Hillslope Processes

NPS photo.

Rockfall is a documented geohazard at El Morro NM where it threatens both the historic inscriptions and public safety. A large rock fall in 1942 destroyed the dam at the Historic Pool, and one occurred along the Inscription Trail in 1999. A pile of talus from a rockfall that occurred prior to 1629 based on the age of inscriptions in the area is still present below the bluff north of the Inscription Rock section. Scars from other historic and prehistoric rockfall are visible all along the face of Inscription Rock and the El Morro bluff.

The prominent vertical jointing, vertical cliff faces and overhanging slabs, and friable nature of the Zuni Sandstone contribute to the rockfall hazard in the monument.

Seismic Hazards

El Morro National Monument has a moderate seismic hazard. The USGS 2014 Seismic Hazard Map indicates that the El Morro area has a 2% chance that earthquake peak ground acceleration of between 10 and 12 %g (percent of gravity) being exceeded in 50 years. This peak ground acceleration is roughly equivalent to VI on the Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale. The expected number of damaging earthquake shaking in the vicinity of El Morro National Monument in 10,000 years is between 4 and 10.

Abandoned Mineral Lands

There are no documented AML sites in El Morro National Monument.NPS AML sites can be important cultural resources and habitat, but many pose risks to park visitors and wildlife, and degrade water quality, park landscapes, and physical and biological resources. Be safe near AML sites—Stay Out and Stay Alive!

Related Link

Burghardt, J. E., E. S. Norby, and H. S. Pranger, II. 2014. Abandoned mineral lands in the National Park System—comprehensive inventory and assessment. Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRTR—2014/906. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado. [IRMA—datastore]

Maps and Reports

- Scoping summaries are records of scoping meetings where NPS staff and local geologists determined the park’s geologic mapping plan and what content should be included in the report.

- Digital geologic maps include files for viewing in GIS software, a guide to using the data, and a document with ancillary map information. Newer products also include data viewable in Google Earth and online map services.

- Reports use the maps to discuss the park’s setting and significance, notable geologic features and processes, geologic resource management issues, and geologic history.

- Posters are a static view of the GIS data in PDF format. Newer posters include aerial imagery or shaded relief and other park information. They are also included with the reports.

- Projects list basic information about the program and all products available for a park.

Source: NPS DataStore Saved Search 2818. To search for additional information, visit the NPS DataStore.

A NPS Soil Resources Inventory project has been completed for El Morro National Monument and can be found on the NPS Data Store.

Source: NPS DataStore Saved Search 2821. To search for additional information, visit the NPS DataStore.

Related Links

Related Articles

El Morro National Monument

National Park Service Geodiversity Atlas

The servicewide Geodiversity Atlas provides information on geoheritage and geodiversity resources and values within the National Park System. This information supports science-based geoconservation and interpretation in the NPS, as well as STEM education in schools, museums, and field camps. The NPS Geologic Resources Division and many parks work with National and International geoconservation communities to ensure that NPS abiotic resources are managed using the highest standards and best practices available.