Last updated: June 14, 2024

Article

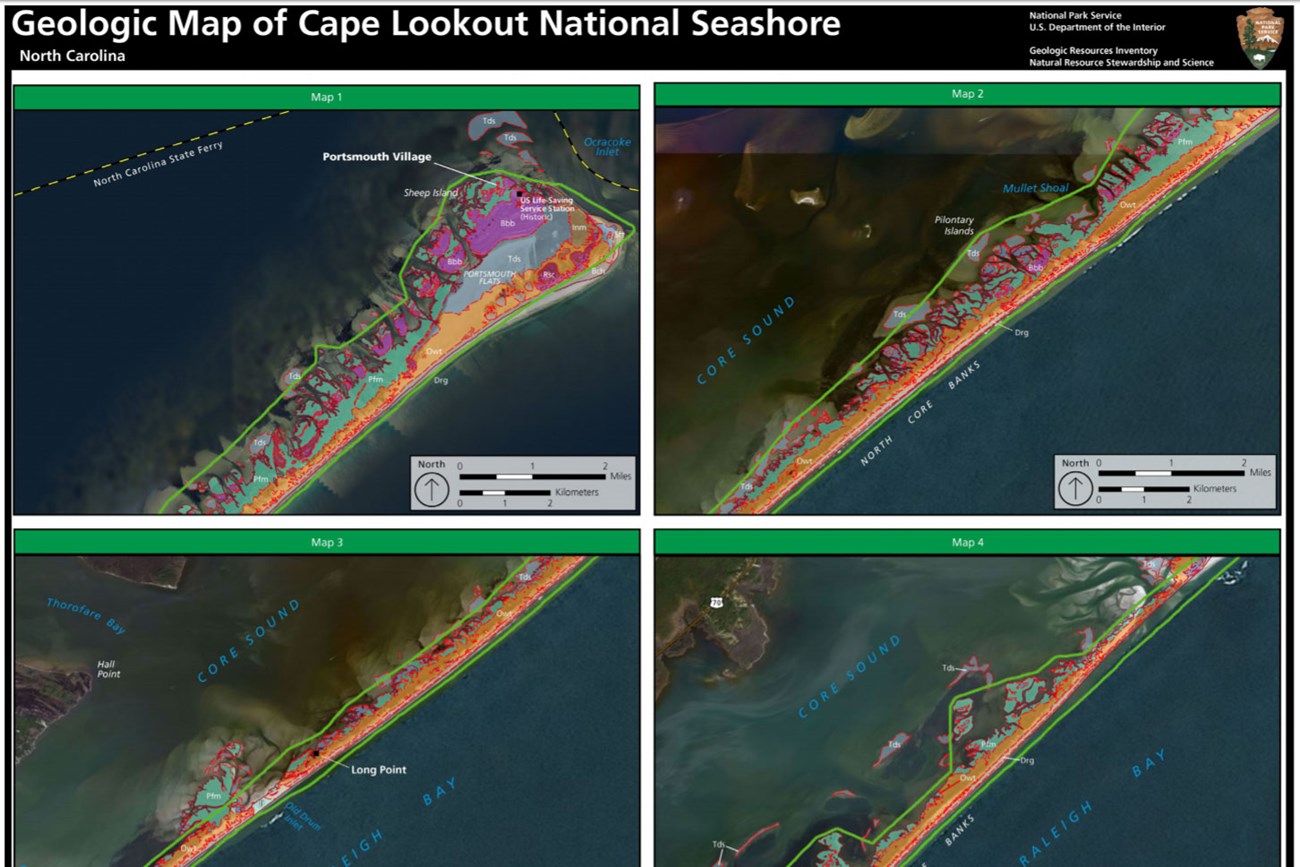

NPS Geodiversity Atlas—Cape Lookout National Seashore, North Carolina

Geodiversity refers to the full variety of natural geologic (rocks, minerals, sediments, fossils, landforms, and physical processes) and soil resources and processes that occur in the park. A product of the Geologic Resources Inventory, the NPS Geodiversity Atlas delivers information in support of education, Geoconservation, and integrated management of living (biotic) and non-living (abiotic) components of the ecosystem.

Geologic Features and Processes

Cape Lookout National Seashore is part of the North Carolina Outer Banks, a barrier island chain within the Atlantic Coastal Plain physiographic province. Its purpose is to preserve the outstanding features and values of an intact barrier island system, where physical, geological, and ecological processes dominate.

The park comprises three long and narrow barrier islands: North and South Core Banks, which extend to the northeast of Cape Lookout, and Shackleford Banks, which extends perpendicularly from Core Banks west of Cape Lookout. The park is bounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the east and south; by the Pamlico, Core, and Back Sounds on its landward side; by Beaufort Inlet (to the west of Shackleford Banks), and by Ocracoke Inlet (to the north of North Core Banks. The park also includes an administrative area on Harkers Island, landward of the barrier islands.

Within the park are a diversity of coastal habitats, including estuaries, mudflats, salt marshes, freshwater marshes, ponds, maritime forest, grassland, dunes, and beaches. The habitats support aquatic and terrestrial plant and animal life including federally protected species. The seashore provides nesting, resting, and feeding habitat for a diverse assemblage of birds.

The Outer Banks are relatively young, geologically speaking. The underlying geologic framework of the park was constructed by repeated changes in relative sea level. This framework controls the sediments available to the modern barrier island, and the ways in which the island responds to natural and anthropogenic processes.

About 5.3 million years ago, sea level was much higher and marine sediments were deposited across much of what is now the coastal plain. Beginning 2.6 million years ago, sea level rose and fell many times as glacial ice grew and receded on the continents and rivers incised the previously deposited marine strata. This created a paleotopography reflected in the estuarine geometry and bathymetry and the location of the barrier islands. These ancient river channels were then backfilled and buried by Holocene sediments during the last 10,000 years as sea level rose to its present level. As a result, the sediments underlying the modern barrier island are a complex assemblage reflecting the various depositional environments, including compact peat and mud, and unconsolidated to semi-consolidated sands, gravels, and shell beds.

Coastal Processes and Features

Storms, waves, tides, sediment transport, inlet dynamics, and sea-level change continue to shape the landforms and rework the thick sediments. Due to the reworking of these older sediments, much of the present Outer Banks is less than 3,000 years old. Storms, waves, and winds continue to shape the islands, along with anthropogenic activities such as inlet and shoreline engineering.

Simple and Complex Barrier Islands

Simple barrier islands such as Core Banks are young, sediment poor, and narrow with low topography. They are particularly vulnerable to sea-level rise and anthropogenic modifications. Complex barriers such as Shackleford Banks are older, sediment rich, and wide with higher elevations, numerous beach ridges, and large dune fields.

Sediment Transport Processes

Sediment transport is much higher along Core Banks than it is along Shackleford Banks. Waves, wind, and storm surge move sediment through the inlets and along and across the islands. Overwash is an important process in building island elevation, expanding marsh platforms, and creating and maintaining early-succession habitat. New sediment comes from three main sources in the nearshore and inner continental shelf: ancient river channels, the Cape Lookout shoal complex, and sand-rich deposits of Pleistocene sediment.

Inlets

New inlets open during storms, when storm surge breaches the island from the ocean or estuarine side. Tidal currents through the inlets deposit sediment, building flood and ebb tidal deltas, which are important for the island sediment budget, marsh building, and long-term island evolution.

Estuaries

Pamlico Sound provides fish nursery, foraging habitats, and seagrass beds. Core Sound is very shallow and microtidal, with winds and tides controlling water level. Back Sound has high tidal flushing around the Beaufort Inlet. Estuarine sediments are derived from the eroded coast, the continental shelf, and ongoing biogenic production.

Groundwater

The surficial aquifer is recharged by rainfall; freshwater floats above denser salt water. Dunes protect the freshwater lens from overwash inundation in smaller storms. Freshwater ponds occur on North Core Banks and western Shackleford Banks.

Coastal Vulnerability and Sea Level Rise

The natural barrier island environment will evolve as sea level continues to rise. Portions of the park are highly susceptible to change due to their low topography. This increases coastal erosion and the potential for overwash, inlet formation, and wetland relocation and migration. Impacts will vary along the coast, depending on the underlying geologic framework and other factors. A considerable increase in sea level may cause the barrier islands to reach a tipping point, resulting in increased landward migration and breaching, reduction in size, and possibly even submergence. Potential climate change impacts include significantly warmer temperatures and a more variable precipitation regime, which may lead to both more frequent droughts and more severe flooding and erosion.

Paleontological Resources

Pleistocene marine shell assemblages are abundant on North Carolina beaches, and it can be difficult to differentiate between fossils and recent remains. Stained shells are considered to be fossils (Riggs et al. 1995; Wehmiller et al. 2003). Black or brown stained shells may correspond to anoxic coastal swamps or estuarine deposits. Brown shells are generally younger (Pleistocene or Holocene) than black shells; however, in anoxic sediments, shells can become blackened in as little as three weeks (Pilkey et al. 1969). The common bivalve Mercenaria commonly changes from chalky white (modern) to yellow-orange (Holocene) to gray-black (Pleistocene). Boring by other invertebrates (Pilkey et al. 1969), abrasion, and trace element composition can also be used to distinguish modern from fossil shells (Wehmiller et al. 2003). Pleistocene and Holocene coastal sediments from the park may include crustacean burrows (from coastal settings); peat and tree stumps (from back-barrier forests and swamps); and shell fragments (from the base of inlet deposits). Middle Marsh and Back Sound, landward of the park, have estuarine mollusks (bivalves and gastropods) and echinoids dated from 2850 BCE to 380 CE (Berelson and Heron 1985).

Quaternary fossils eroded out from nearshore outcrops wash onto the park shoreline. A late Pleistocene terrace crops out in 9 to 12 m (30 to 40 ft) of water. Fossils from this unit include sponges, bryozoans, polychaete worm tubes, barnacles, echinoderms, and various mollusks (bivalves, gastropods, and scaphopods). Offshore ridges of coralline algae (a type of reef-forming algae), up to 26,250 years old, also contribute to the sediment that may wash up (Cleary and Thayer 1973). There is also the potential for vertebrate remains to wash onshore, as evidenced at Cape Hatteras to the north (Tweet et al. 2009).

All NPS fossil resources are protected under the Paleontological Resources Preservation Act of 2009 (Public Law 111-11, Title VI, Subtitle D; 16 U.S.C. §§ 470aaa - 470aaa-11).

Regional Geology

Cape Lookout National Seashore is a part of the Coastal Plain Physiographic Province and shares its geologic history and some characteristic geologic formations with a region that extends well beyond park boundaries.

- Scoping summaries are records of scoping meetings where NPS staff and local geologists determined the park’s geologic mapping plan and what content should be included in the report.

- Digital geologic maps include files for viewing in GIS software, a guide to using the data, and a document with ancillary map information. Newer products also include data viewable in Google Earth and online map services.

- Reports use the maps to discuss the park’s setting and significance, notable geologic features and processes, geologic resource management issues, and geologic history.

- Posters are a static view of the GIS data in PDF format. Newer posters include aerial imagery or shaded relief and other park information. They are also included with the reports.

- Projects list basic information about the program and all products available for a park.

Source: NPS DataStore Saved Search 2765. To search for additional information, visit the NPS DataStore.

A NPS Soil Resources Inventory project has been completed for Cape Lookout National Seashore and can be found on the NPS Data Store.

Source: NPS DataStore Saved Search 2747. To search for additional information, visit the NPS DataStore.

GRI Geology Image Gallery

Related Links