Last updated: November 24, 2021

Article

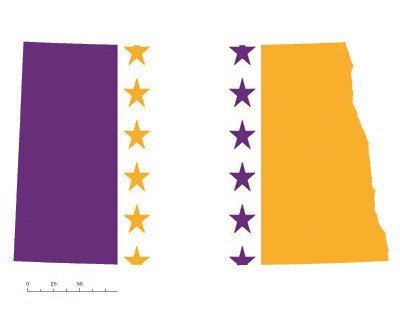

North Dakota and the 19th Amendment

Women first organized and collectively fought for suffrage at the national level in July of 1848. Suffragists such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott convened a meeting of over 300 people in Seneca Falls, New York. In the following decades, women marched, protested, lobbied, and even went to jail. By the 1870s, women pressured Congress to vote on an amendment that would recognize their suffrage rights. This amendment was sometimes known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment and became the 19th Amendment.

The amendment reads:

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

Although the women’s rights movement was born in New England, women first won suffrage victories in the West. In the Dakota Territory, women were able to vote in school elections beginning in 1883. Legislation that would have provided full suffrage to women lost by one vote in 1875. A similar bill passed the territorial legislature in 1885 but was vetoed by the territorial governor, Gilbert Pierce. If Governor Pierce had not struck down the law, women from the Dakota Territory would have joined those in the Wyoming and Utah territories in winning voting rights on the same terms as men.

State Historical Society of North Dakota. SHSND D0634-0001.

When North Dakota became a state in 1889, the state constitution continued to protect women’s right to vote in school elections but did not expand their enfranchisement. A few determined women lobbied for full suffrage throughout the rest of the nineteenth century. Linda Slaughter, who with her husband Dr. Frank Slaughter helped to establish the town of Bismark, was a vocal advocate for both women and Native Americans. Elizabeth Preston Anderson, who was President of the North Dakota chapter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) campaigned year after year for the passage of suffrage measures through the legislature. Though the organization’s main interest was in preserving and enforcing the prohibition law, the WCTU also favored woman suffrage. Because of Anderson’s record-keeping, we have evidence of a defeat for woman suffrage in North Dakota that was nearly a victory. In 1893, a bill enacting full voting rights for women passed the North Dakota legislature and it looked like the governor would sign it. However, the speaker of the North Dakota House refused to sign the measure. Then the bill was “lost” on its way to the governor. The House expunged the record as if the proceedings never happened.

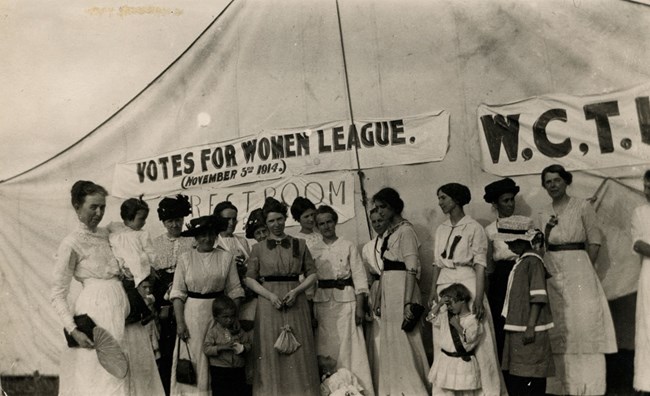

State Historical Society of North Dakota. SHSND 10204.

North Dakota women were also on the forefront of organizing for woman suffrage. Dr. Cora Smith Eaton formed the Grand Forks Equal Suffrage Association in the 1880s. They held a suffrage convention in November1895, but soon after Dr. Eaton moved to Washington State and worked for women’s rights there. An accomplished mountaineer, she planted a Votes for Women banner near the summit of Mount Rainier in 1909. The Votes for Women League formed in Fargo in 1912, a year after the North Dakota legislature amended voting laws to define voters as “male persons,” which was a blow to the woman suffrage movement.

North Dakota suffragists continued to push for expanded voting rights. In 1913, a woman suffrage bill passed the legislature but then was put to the male voters of the state and defeated in 1914. Three years later, there was finally a small victory when North Dakota lawmakers passed limited suffrage. The bill allowed women to vote for presidential electors and for some municipal positions. This measure was not put to the voters and was signed into law by the governor.

National Woman's Party Records. The Library of Congress

This incremental progress was frustrating to many suffragists who grew disillusioned with working for the right to vote on the state level. Women from North Dakota joined the fight for a federal amendment enfranchising women. Some participated in more confrontational demonstrations such as the National Woman’s Party pickets of the White House demanding that President Wilson support a constitutional amendment enfranchising women. Beulah Abingdon of Fargo, press secretary for the NWP, was sometimes called “The Prettiest Picket.” She was arrested during a protest in August 1917.

After decades of arguments across the country for and against women's suffrage, Congress finally approved the 19th Amendment in June 1919. After Congress passed it, at least 36 states needed to vote in favor of the amendment for it to become part of the U.S. Constitution. This process is called ratification.

On December 1, 1919, North Dakota voted to ratify the 19th Amendment. By August of 1920, 36 states (including North Dakota) ratified the amendment, ensuring that all across the country, the right to vote could not be denied based on sex.

North Dakota Places of Women's Suffrage: North Dakota Executive Mansion

Built in 1884, the North Dakota Executive Mansion was the home of the governor. Twenty different governors lived in the house from 1893 up to 1960. Lynn Frazier served as the governor from 1917 to 1921 and lived in the house with his wife and children. In 1919, he ratified the 19th Amendment for the state of North Dakota, recognizing women’s suffrage rights. The house is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is open for tours by appointment.

The North Dakota Executive Mansion is an important place in the story of ratification. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Pla