Last updated: January 14, 2026

Article

The Bunker Hill Monument Fair of September 1840

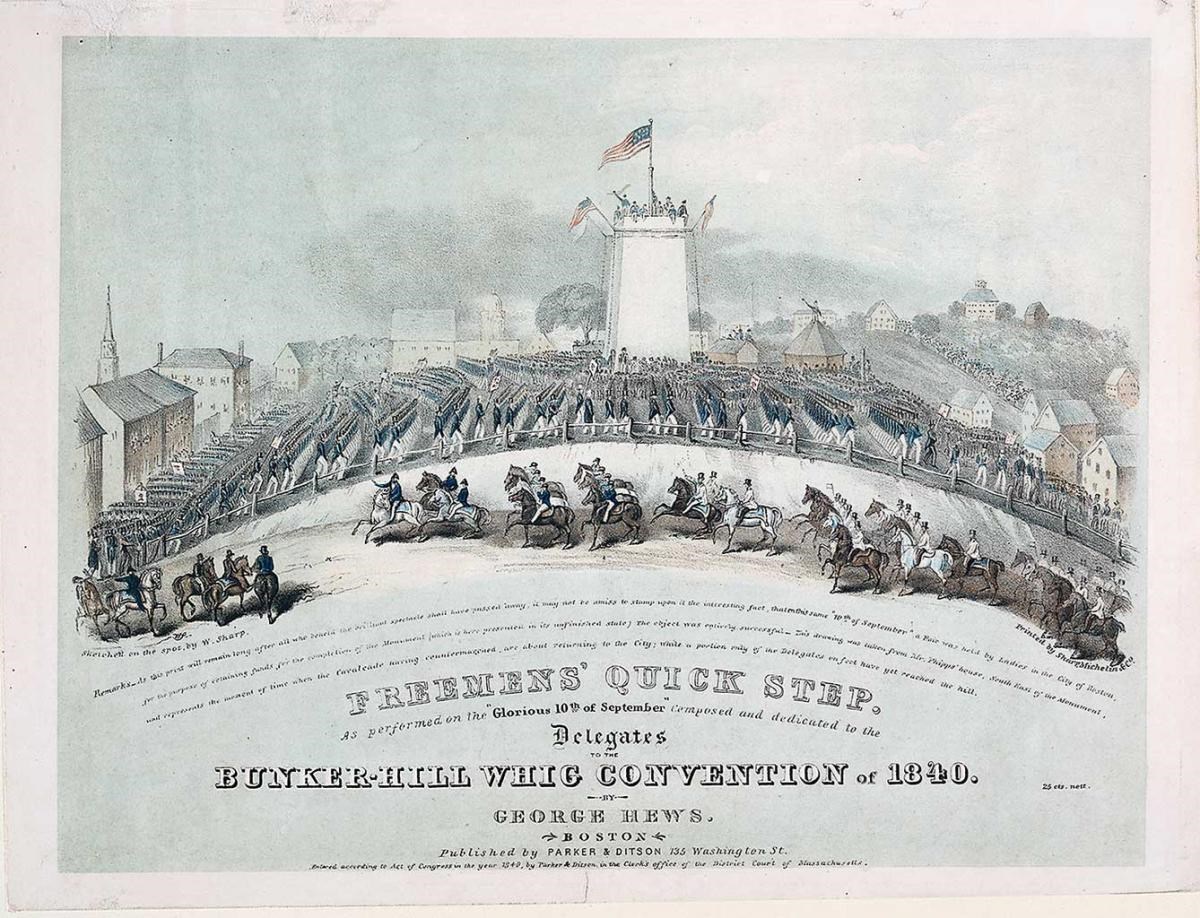

William Sharp, “Freeman’s Quick-Step. Bunker Hill Whig Convention of 1840.” Boston Athenaeum, Selections from "Acquired Tastes."

Dreaming of a Bunker Hill Monument

Let our age be the age of improvement. In a day of peace, let us advance the arts of peace and the works of peace. Let us develop the resources of our land, call forth its powers, build up its institutions, promote all its great interests, and see whether we also, in our day and generation, may not perform something worthy to be remembered.[1]

This wish that Bostonians use peaceful means to take the lead in advancing the new nation was the core message of Daniel Webster’s address to 15,000 spectators on June 17, 1825. On this day, the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill, attendees were gathered to witness the laying of the cornerstone for the Bunker Hill Monument. The Monument was intended to become a grand symbol for these optimistic American goals.

Fifteen years later, in 1839, the Bunker Hill Monument was not yet even close to complete. During those years, the Bunker Hill Monument Association had been trying to bring in funding, but due to a series of issues with architects, contractors, and funding sources, the Association’s members were in a despondent mood at their 1839 annual meeting. Despite the offer of $10,000 each by two generous men, the annual report deemed it "exceedingly doubtful whether the present generation would have the pleasure to see the monument completed." Indeed, the two offers of a total of $20,000 had been made dependent on the Association’s receiving an additional $30,000 in donations from members of the public. The donation strategy had fallen short in a number of attempts since 1825.[2] Why would it work now?

George Washington Warren, The History of the Bunker Hill Monument Association during the First Century of the United States of America (Boston: James Osgood & Company, 1876), p. 309.

Fundraising Failures and One Great Success

In 1823, the Bunker Hill Monument Association (BHMA) was formed by leading men of Boston with the goal of building a monument "to the memory of those statesmen and soldiers who led the way in the American Revolution." The founders of the fundraising effort instituted "subscriptions," one-time $5 payments, for other men to join the BHMA. Circulars distributed throughout New England described the Battle and BHMA's plans for a monument to June 17, 1775. Initially successful, this concept soon derailed, as men who donated much larger sums did not see their investment paying off. An array of difficulties pushed the date of the Monument's completions farther and farther into the future. Many drastic measures were taken to keep the project from becoming untenable: administrators and contractors were changed, construction plans and methods altered.

Women associated with the men of the BHMA held their own fund drive that mimicked the men’s subscription tactic. Many men pushed back, saying that women had no right to donate money from household resources. Sarah Josepha Hale, the women’s fundraising coordinator, stepped onto her Ladies' Magazine public platform and campaigned for women to contribute $1. Her stance was strongly criticized in newspapers that favored men only to raise Monument funds. By 1840, the Ladies' Fund amounted to only $2,937.90.[3]

In the summer of 1840, a Boston women’s sewing circle of Seaman's Aid Society members came up with the idea of using a familiar form, a women's fair, to generate the necessary $30,000 for the BHMA. The sewing circle, comprised of female former fundraisers for the Bunker Hill Monument, approached the BHMA yet again with this tactical change. The BHMA appointed these women as a Fair Committee.

This Committee contacted women’s networks throughout New England and down the Atlantic coast through newspaper articles and letters. These articles and letters requested that women's clubs donate all manner of crafts, pieces of art, and kitchen specialties. Six weeks later, the Bunker Hill Monument Fair was held.[4] How was this incredibly short timeline possible? Sarah Josepha Hale’s 1831 article on Ladies' Fairs shines some light onto this question:

Considering Ladies' Fairs among the chief graces of charity fostered by the needle, we give, in our plate, a beautiful illustration of industry, a young lady, surrounded by all the appurtenances and means of elegant enjoyment, is devoting herself sedulously to the old-fashioned employment of her needle, working for the Ladies' Fair, and thinking of a destitute and sick family to whom she hopes a part of the proceeds will be devoted to relieve.[5]

Ladies' fairs gave women their own space to work productively and contribute to social causes in an organized form. What could be a greater social cause than funding a grand monument's construction on a Revolutionary War battlefield?

Women Change the Fundraising Tactics

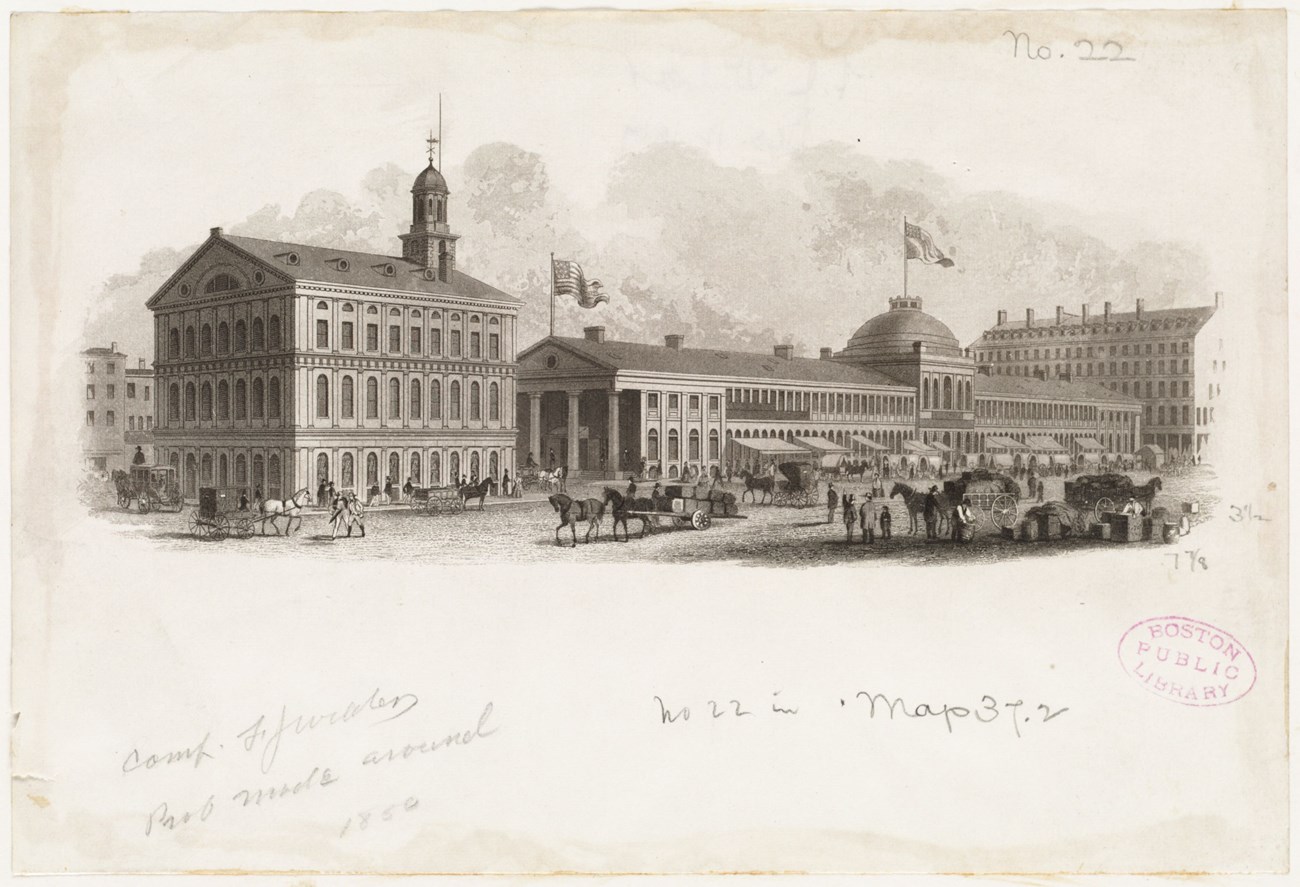

From September 10 to September 15, 1840, a women's committee associated with the Bunker Hill Monument Association held a fundraising fair that, in the short span of five days, brought in substantially more cash than the goal of $30,000. The Bunker Hill Monument Fair occupied the second floor of "the Faneuil Hall Market" (today known as Quincy Market) right on the edge of the harbor in Downtown Boston.

Ticket sales alone accounted for $9,884.59, close to one third of the goal sum. On the first day, Monday Sept 10, tickets cost 50 cents per person and 4,000 people paid to attend, totaling $2000. As ticket prices were reduced to 25 cents per person for the following four days, Tuesday through Friday, came an additional 31,600 people visited the Fair, bringing in approximately $7,900 in addition to the initial $2,000 in ticket sales. Considering Boston’s population of 93,383 in 1840, the total Fair visitation accounted for nearly 40% of Boston’s population, at 35,600.[6]

Visitors from all corners of New England gained entrance to the second-floor fair by climbing a temporary stairway erected in the street. When they reached the top of these stairs, they found themselves in the astounding central pavilion, with its large double dome topped with a glassed-in cupola above them. From here, they could explore 63 fair tables and additional displays, reaching from the East to the West wing.

Visitors encountered women from seventeen local women’s groups, representing communities from Charlestown to Worcester, New Bedford to Nantucket, Lowell to Salem. As the 35,600 visitors explored, they purchased needlework, fabrics, household items, fresh or preserved delicacies, and much more, making the fair’s total profit $33,067 and 73 ½ cents (plus $9,885.34 earned afterwards). This profit, reached in five days, achieved the fundraising goal the Association had failed to attain for years.[7]

“Faneuil Hall and Quincy Market,” ca. 1850, Boston Public Library.

Location, Location, Location!

The Bunker Hill Monument Fair's location played a strong role in the event’s success. It was held at Quincy’s Market, completed in 1825 through a partnership between Boston’s city government and local businesses. The Market building served as the centerpiece of Boston's mayor John Quincy's sweeping neighborhood improvement project, with the primary goals of promoting Boston harbor’s economic strength and completely updating and beautifying the harbor area’s streetscape. This enormous Greek Revival structure standing on the water’s edge dominated downtown Boston. People aboard entering the harbor saw the Market as a Greek temple, architectural proof of the city’s status as the "Athens of America."[8] Holding the Fair in this structure both underlined the Bunker Hill Monument’s significance as a symbol of renewal and destiny and also brought women’s contributions to local and national New Republic culture[9] to the forefront.

The Bunker Hill Monument Association's Fair of 1840 stood on Quincy's Market's granite shoulders. Both made use of traditional market forms, but with "unprecedented" scales and materials. Quincy's Market was built of granite mined in the nearby coastal town of Quincy. It exemplified the Boston Granite style developed in the early 1800s (and today still a key reference point in designing large buildings for downtown Boston). The Bunker Hill Monument was to be constructed of the very same granite on a high hill in Charlestown, echoing the Boston Granite architecture.

Since its opening in 1825, Quincy's Market had given citizens 15 years of access to local products with the imported products that a mercantile harbor could offer fresh off trading ships, all in a noble setting intended to embody Boston's newly-crafted economic success. Quincy's Market's ground floor was dedicated to meat, fish, and produce dealers, also textiles, fabrics, household wares, while the second floor had "an elegant rotunda capped by the dome" to be used for assemblies and exhibitions of wares displayed by trade groups representing the new American industrial economy. Stalls on the outside of the market sold tea, spices, rum, cotton, and molasses – all imported by "the new merchants" of the New Republic. The flanking North & South Market, brick buildings with granite facades, housed small businesses also selling trade goods. Visitors to the Monument Fair stepped into a grand building in this central and thriving location that promised what could be for the Bunker Hill Monument, should the funding goal be reached.[10]

Why Did Women Support the Monument Fund Drive?

Women organized, ran, and administered the immensely successful Bunker Hill Monument Fair. Did any of these women leave a record of why they stepped into this particular role? Indeed, many of them recorded their contributions to the Fair: in letters and diaries, "official" committee records, press packets, and articles published in women's magazines and the New England press. A particularly articulate writer was Sarah Josepha Hale, who, as an "authoress and editress" of the Boston-based Ladies' Magazine and Literary Gazette, used her consciously gendered identity as a source of power and authority. While by no means an innovative approach, Hale serves as one prominent example of this cultural phenomenon.

Most American women of status professed no desire to leave the domestic world of the Early Republic (or "New Republic," as they termed their era). Some of them nevertheless stepped into public discussions, claiming particular, superior female insight and skills. Hale’s editorial commentary on the Bunker Hill Monument’s sorry state in the Ladies' Magazine and Literary Gazette reached a wide audience of both genders, as local newspapers reprinted and discussed her writings.

As early as 1830 and 1831, Hale defined the societal role she shared with her counterparts, using her Ladies’ Magazine and Literary Gazette as a platform. She linked this role to the imperative need for women to join the fundraising for the completion of the Bunker Hill Monument. The following texts hold up very similar national goals to those Daniel Webster proposed in 1825. However, Hale described how willing women could play a key role in defining and passing on a new American identity of ethical excellence in the "New Republic":

Will not the free people of our Republic be among the first to endeavor to shake off the dominion of selfishness, and make the object of their ambition, moral and mental excellence, rather than wealth? This change must be wrought by education; and here the women of America are deeply responsible. They first awaken the moral feelings, and it is by them that the moral sentiments are directed, and the habits which finally stamp the character, fixed. (February 1830)

Without elevating associations [symbolism] that make us better and wiser, the building a Monument would be no more entitled to praise or consideration than building a mill. (April 1831)[11]

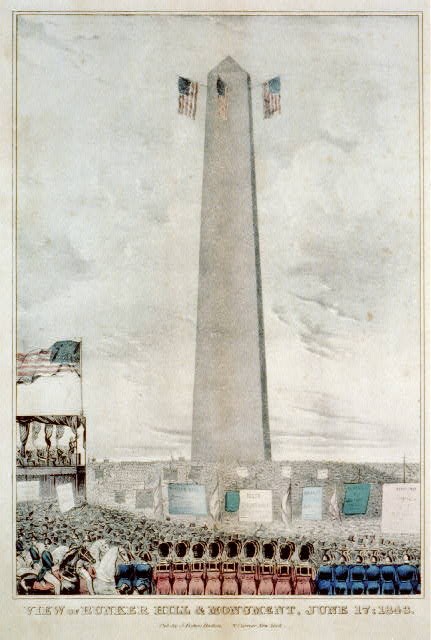

“The View of Bunker Hill & Monument, June 17, 1843,” New York: J. Fisher and N. Currie, Library of Congress.

What Impact Did the Monument Fair Have?

On Saturday July 23, 1842, at 6 AM, the top stone of the Bunker Hill Monument was laid, a "little over two years from the first suggestion of the Fair." Several hundred citizens gathered with the Bunker Hill Monument Association's Board of Directors to witness this final step in the incredibly long and arduous journey from idea to reality.[12] While men’s tactics for fundraising had failed, women's creativity and use of their community-based social networks successfully brought the Bunker Hill Monument to life.

Footnotes:

[1] Daniel Webster, “The First Bunker Hill Monument Oration, June 17, 1825.” In: Daniel Webster, The Bunker Hill Monument Orations (New York: Clark and Maynard, 1843), p. 28.

[2] George Washington Warren, The History of the Bunker Hill Monument Association During the First Century of the United States of America, (Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1877), p. 298.

[3] Richard Frothingham, History of the siege of Boston, and of the battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill: also, an account of the Bunker Hill Monument, with illustrative documents (Boston: C.C. Little and J. Brown, 1851), pp. 341ff; Sarah Josepha Hale, Ms. letter, Feb. 13, 1830, Boston Public Library; Bunker Hill Monument Assn, records, Massachusetts Historial Society, Boston; Sherbrooke Rogers, Sarah Josepha Hale: A New England Pioneer, 1788-1879 (Grantham, NH: Thomson & Rutter, 1985), pp. 46, 50.

[4] Frothingham, History of the siege of Boston, p. 350; Rogers, Sarah Josepha Hale, pp. 46, 50. In her study of women’s reform efforts in Worcester, MA in the antebellum 19th century, Carolyn J. Lawes states that sewing circles were “for antebellum women what the political party was for antebellum men: a forum for good fellowship, mutual improvement, and social activism,” in C. J. Lawes, Women and Reform in a New England Community, 1815-1860 (University of Kentucky Press, 2000) p. 6.

[5] Sarah Josepha Hale, Ladies’ Magazine and Literary Gazette, April 1831, Vol. III, no. II, p. 290.

[6] John Quincy, Jr., Quincy’s Market: A Boston Landmark (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2003), p. 93; Warren, The History of the Bunker Hill Monument Association, p. 298; Samuel H. Russell, Treasurer Bunker Hill Monument Association, “Accounts of Miss Mary Otis, Treasurer of the Ladies' Fair held in Boston, September, 1840. Presented, through the Treasurer, to the Bunker Hill Monument Association by Miss Mary Otis, May 24, 1864. In: Proceedings of the Bunker Hill Monument Association on the Occasion of Their Forty-First Anniversary, June 17, 1864 (Boston: Press of Geo. C. Range & Avery, 3 Cornhill, 1864), pp. 21-31.

[7] John Quincy, Jr., Quincy’s Market, pp. 111-112; Warren, The History of the Bunker Hill Monument Association, p. 300; Russell, “Accounts of Miss Mary Otis,” pp. 21-31. Compare these huge profits to weekly wages in MA for laborers in the skilled trades in 1840, which stood at $3-$10, totaling an annual income of ca. $150 - $500, in the best of circumstances. In other words, in only five days, the fair brought in enough cash to equal annual income for 66 to 220 skilled Massachusetts laborers. The income estimates assume a six-day work week for 50 weeks/year; note that not many could rely on steady, year-round full employment. (Carroll Davidson Wright, “Historical Review of Wages and Prices, 1752-1860”, pp. 38-60. In: Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of Labor: Comparative wages, prices, and cost of living. Sixteenth annual report of the Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of Labor, for 1885 (Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Co., 1889).) To provide one specific example, the Seaman’s Aid Society of Boston (run by the same female network organizing the fair) determined that a fair wage, placing a family above poverty level, for women seamstresses under their care would be $3/week, ca. $150 annual income, if that (Isabelle Webb Entrikin, Sarah Josepha Hale and Godey’s Lady’s Book (Philadelphia: Lancaster Press, 1946, p. 40).

[8] John Quincy, Jr., Quincy’s Market, pp. 84, 87, 91, 109; Josiah Quincy, A municipal history of the town and city of Boston, during two Centuries: From September 17, 1630, to September 17, 1830 (Boston: C.C. Little and J. Brown, 1852), pp. 74-87; Douglass Shand-Tucci, Built in Boston, City and Suburb (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1977); Keith N. Morgan, “Quincy Market,” Society of Architectural Historians: https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/MA-01-GC5. Boston as the “Athens of America” was a metaphoric title given to the city by William Tudor, a leading citizen, in 1819 (see: Robert J. Allison, “Why Was Boston the Athens of America?” Old North Church Blog, Jan 27, 2017, https://oldnorth.com/2017/01/25/why-was-boston-the-athens-of-america/; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Tudor_(1779%E2%80%931830)).

[9] The “New Republic” was an era of American culture in the early 19th century. In our context, the term is shorthand for northern East Coast industrial growth coupled with various groups of Americans trying to form their identities in harmony with national ideals rooted in the U.S. Constitution. Depending who these groups were, identity formation could be relatively simple, or it could be a painful process that sometimes failed completely.

[10] An ironic twist is that the cornerstones for both Quincy’s Market and the Bunker Hill Monument were laid in 1825. In fact, the Bunker Hill Monument Association invested in the Market’s construction. The market house was completed and occupied within 16 months, while Bunker Hill Monument was still under construction 16 years later. John Quincy, Jr., Quincy’s Market, pp. 84, 87, 91, 109; Josiah Quincy, A municipal history, pp. 74-87; Shand-Tucci, Built in Boston; Morgan, “Quincy Market.”

[11] Patricia Okker, Sarah J. Hale and the Tradition of Nineteenth-Century Women Editors (Athens & London: The University of Georgia Press: 2008 (1995), p. 1; “The Worth of Money.” In: Ladies’ Magazine and Literary Gazette, February 1830, Vol. III, No. II, p. 52; “Ladies’ Subscription.” In: Ladies’ Magazine and Literary Gazette, April 1831, Vol. III, No. II, p. 175.

[12] Warren, The History of the Bunker Hill Monument Association, pp. 303-304.