Last updated: March 9, 2022

Article

International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union

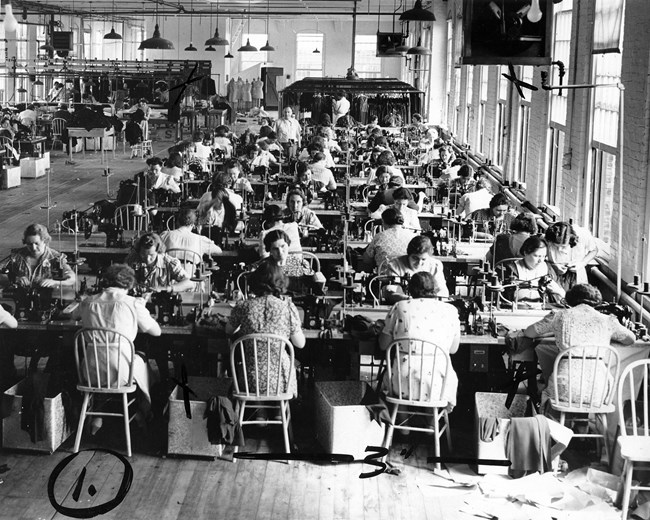

Courtesy Library of Congress.

The International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) was one of the largest labor unions in the United States in the 1900s. It represented hundreds of thousands of clothing industry workers, most of them women. Two successful strikes in 1909 and 1910 won power for the union. Members and their allies pushed for new laws to protect organized labor. They gained broad support after the devastating Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire in 1911. By the 1920s, the ILGWU was a political heavyweight.

Formation and Early Strikes

Seven local unions in New York City founded the ILGWU on June 3, 1900. Most of its members were young, immigrant women from Eastern and Southern Europe. Many of them were Jewish. The ILGWU cemented its power with two large strikes in New York City. In 1909, 23-year-old Clara Lemlich galvanized a crowd of workers meeting at Cooper Union.[1] She climbed up to the speakers’ platform and declared:

“I have no further patience for talk. I am a working girl, one of those striking against intolerable conditions. I am tired of listening to speakers who talk in generalities. … I make a motion that we go out in a general strike.”

Later in life, she remembered her activism, saying “Ah—then I had fire in my mouth!”

Tens of thousands of workers agreed and joined Lemlich and other leaders like Rose Schneiderman on the picket line. The strike became known as the “Uprising of 20,000.” At the time, it was the largest strike by women workers in US history. The strikers demanded better hours, safer conditions, and fairer pay. They received support from a group of wealthy women who organized via the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL). Months later, 60,000 male and female cloakmakers walked out in another huge strike known as the “Great Revolt.”

Courtesy Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Cornell University.

The ILGWU was an early example of an “industrial union.” In this setup, all workers in an industry would join the same union, regardless of their individual jobs or skill sets. Supporters of industrial unionism argued that it would promote more unity and solidarity than the older style of “craft unionism,” which divided workers by their job function or skill level.

The strikes led to a spike in the ILGWU’s membership and forced major concessions from factory owners. But the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire the following year showed that much more was needed.[2] One hundred and forty-six garment workers died in the conflagration. Some of them had been trapped behind locked doors, a common management practice to reduce theft. The uproar that followed the tragedy spurred important changes in labor law and enforcement. It galvanized leaders like Frances Perkins, who went on to shape the policies of the New Deal.

Expansion, Diversification, and Criticism

Under the leadership of longtime president David Dubinsky (1932-1966), the ILGWU more than doubled its membership. It expanded its geographic reach beyond the Northeast, and worked to organize Black, Latina, and Asian employees in the South and West. Unions were less common in these areas, and employer resistance could be fierce. But local leaders like Sue Ko Lee in San Francisco and Emma Tenayuca in San Antonio worked with the ILGWU to win improvements for their communities.

As the union grew and diversified, the disconnect between its leadership and its membership could be contentious. Women leaders like Rose Pesotta had long complained that the top leadership was almost exclusively male even though most members were women. Pesotta, who had led the grueling Dressmakers General Strike in Los Angeles in 1933, resigned from the ILGWU’s General Executive Board in 1942.[3] Frustrated by the sexism she experienced from male leadership, she charged that the "men to whom I have been so useful" chose not to recognize her competence as a leader. As the racial diversity of the union increased, members of color demanded that they be represented too.

Courtesy Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Cornell University.

Education, Healthcare, Housing, and Art

The ILGWU aspired to improve its members’ lives in ways that went beyond pay and working conditions. It developed workers’ education programs that trained members not only in the ins and outs of organizing a strike, but also in history, economics, and international relations. The ILGWU sponsored health clinics and invested in affordable housing.[4] A resort in the Poconos, Unity House, hosted members for summer vacations.[5]

The ILGWU made its mark on the arts and culture as well as politics. In the 1930s, it sponsored a satirical musical revue called Pins and Needles. Originally written as entertainment for strikers on picket lines, it starred a cast of garment workers and became a Broadway hit. It ran from 1937 until 1940 and was performed at the White House for Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt in 1938. The revue commented on current events from a union perspective. Numbers like “Doing the Reactionary” and “Not Cricket to Picket” satirized bosses and fascist sympathizers. Its performers constantly revised and updated it in response to the news.

Later Years

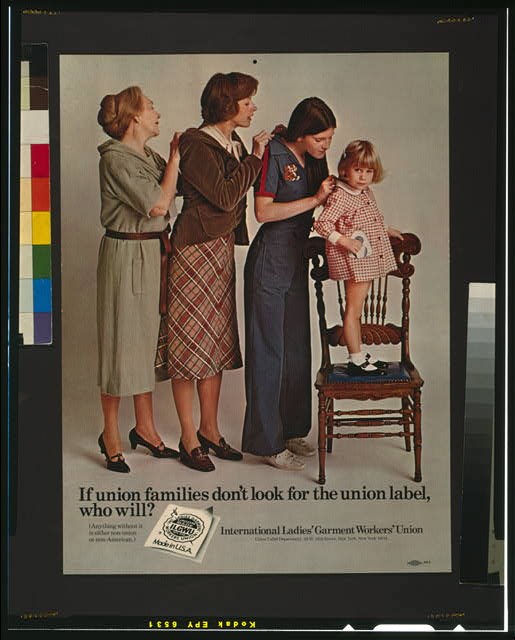

In the 1970s and 1980s, the garment industry in the US began to decline as companies competed with cheaper imports from overseas. In response, the ILGWU mounted a campaign to encourage consumers to buy union-made American goods. In television commercials, workers sang a catchy song urging shoppers to “Look for the Union Label.”

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In the 1990s, the ILGWU merged with the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union to form the new Union of Needletrades, Industrial and Textile Employees (UNITE), now UNITE HERE.

Notes

[1] The Cooper Union’s Foundation Building was designated a National Historic Landmark on July 4, 1961 and listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966.

[2] The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, also known as the Brown Building, was added to the National Register of Historic Places and designated a National Historic Landmark on July 17, 1991.

[3] The Anjac Fashion Building (also known as the Platt Building) was one of the sites of the 1933 strike. It is part of the Broadway Theater District in Los Angeles, California and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 9, 1979.

[4] One of the ILGWU’s housing complexes was Penn South, which opened in 1962 in New York City. The co-op includes the Bayard Rustin Residence, which was added to the NRHP on March 8, 2016.

[5] Unity House, now abandoned, is located approximately three miles from Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area.

Bibliography

ILGWU Online Exhibit. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Cornell University Library. Originally published August 2011. https://ilgwu.ilr.cornell.edu.

- Please visit the Kheel Center's ILGWU site for an extensive bibliography to guide further reading.

Katz, Daniel. All Together Different: Yiddish Socialists, Garment Workers, and the Labor Roots of Multiculturalism. New York: New York University Press, 2011.

Orleck, Annelise. Common Sense and a Little Fire: Women and Working-Class Politics in the United States, 1900-1965. 2nd ed. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Von Drehle, David. Triangle: The Fire That Changed America. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2003.

Article by Ella Wagner, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

Tags

- women in the labor movement

- labor history

- women's history

- new york

- new york city

- european american history

- latino american history

- asian american and pacific islander history

- african american history and culture

- workers

- women and the economy

- labor rights

- labor reform

- social movements

- jewish history

- women and politics

- shaping the political landscape