Last updated: January 22, 2024

Article

Gay and Lesbian Town Meeting

A New Fight for Freedom

"We have to think that we are part of a great social movement that is going to bring positive contributions socially in a way that people today perhaps can’t even understand or imagine."

-West Hollywood City Councilor Stephen E. Schulte, June 13, 1989[1]

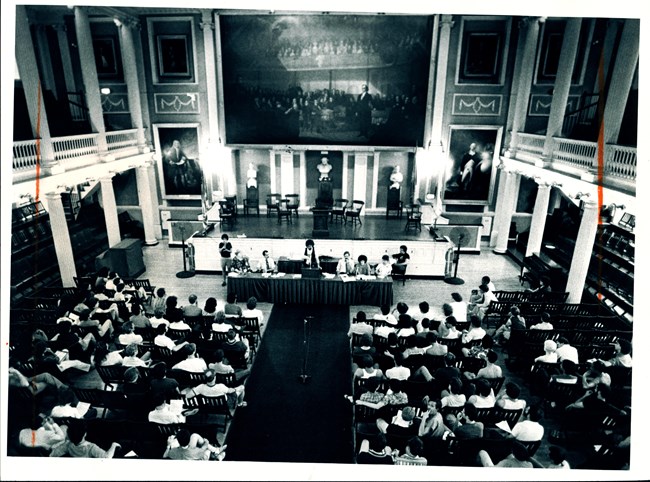

Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections

Gay and Lesbian Town Meeting, held in Faneuil Hall from 1977 to around 1996, added to the extensive histories of liberty and activism which unfolded within that storied space. Noteworthy keynote speakers and ordinary citizens used the open forum to voice their concerns and to fight for their right to exist in the world as their truest selves. The discussions lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, and transgender people held every year, and the action those discussions inspired, made an impact that we can still observe in our society today.

LGBTQ+ people have lived in Boston since its founding, but this group's political and social mobilization began mainly in the 1900s. As early as the 1950s, gay men and lesbians found fellowship in the Mattachine Society and the Daughers of Bilitis, respectively. These organizations helped their members feel less ashamed of their identities and educated a society that largely viewed LGBTQ+ people as criminal or diseased.[2] A chapter of the Mattachine Society existed in Boston from the late 1950s to the early 1960s, but unlike the chapters in New York and San Francisco, it remained small and quickly crumbled under the weight of constant infighting.[3]

The Stonewall Uprising in New York City in 1969 brought renewed energy to the cause. When police raided the Stonewall Inn, a popular Greenwich Village gay bar, the bar’s patrons fought back, tired of the frequent and often cruel raids. In the weeks that followed the uprising, a radicalized community created new organizations and set their sights on liberation. LGBTQ+ people in Boston felt the impact of the events in New York and sprang to action. The first Boston Pride celebration occurred in June of 1970, commemorating the first anniversary of Stonewall. In 1973, Gay Community News emerged as a source of information and opinion concerning events in Boston and beyond; GCN became the longest-running gay newspaper with a national audience by 1991.[4] Between the fiery and prolific journalists at GCN and the early political success of LGBTQ+ candidates such as Elaine Noble, the first openly gay person elected to a state legislature, Boston's LGBTQ+ community enhanced the national movement with its intelligence and revolutionary spirit.[5]

The Right to Love, The Right to Exist

"We are everywhere, we belong to every group and our freedom must belong to every group."

-Boston City Councilor David Scondras, June 7, 1984[6]

Boston's LGBTQ+ community booked Faneuil Hall for its first Gay and Lesbian Town Meeting in 1977.[7] The meetings always occurred in June as part of annual Pride activities, and they almost always took place in Faneuil Hall. For many years, 200 to 300 people attended these meetings, though the 1983 meeting drew a crowd of 600.[8] At the first few town meetings, representatives from local organizations spoke for three to five minutes each, then the moderators opened the floor to anyone who wished to speak. This format deliberately imitated that of the old Boston town meeting, as a nod to the revolutionary era and a symbol of their own movement's legitimacy in the history of American political protest. As one brochure explained:

Susan Fleischmann, Gay Community News

Town Meeting has been a New England tradition for centuries, exemplifying the spirit of grassroots citizens’ democracy which is this region’s heritage. New Englanders have long gathered to address the issues facing them, both large and small, in an open, participatory, and lively forum. The model is one of the citizenry taking direct responsibility for their own lives and affairs.

Fusing New England tradition with the more modern rite of Lesbian and Gay Pride, the lesbian and gay community of Greater Boston has held its own town meetings in historic Fanueil [sic.] Hall for years.[9]

By the mid-1980s, the focus of the event, at least in promotional materials, shifted toward the participation of one or two keynote speakers. The "open mic" segment, however, remained a key component of town meeting throughout the event’s roughly twenty-year run in Faneuil Hall.[10]

The issues on the table from year to year varied as much as the speakers themselves. Especially at the start of a new decade, activists used the Town Meeting to form a plan of action for the coming year or years. Representatives from various grassroots organizations spoke in the Town Meeting about their work to improve the status and wellbeing of the community. The Greater Boston Lesbian and Gay Political Alliance (later the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Political Alliance of Massachusetts)—the key organizer behind the annual town meetings[11] —and the Massachusetts Gay and Lesbian Political Caucus focused on teaching politicians about social justice and lobbying for LGBTQ+ civil rights legislation. Political changes and the electoral process became popular topics at a number of town meetings as a result of these groups’ hard work. The meetings inspired LGBTQ+ Bostonians to take a more active interest in politics, support candidates who vowed to expand their rights, and lobby on the behalf of key legislation such as Massachusetts’s first LGBTQ+ civil rights bill.

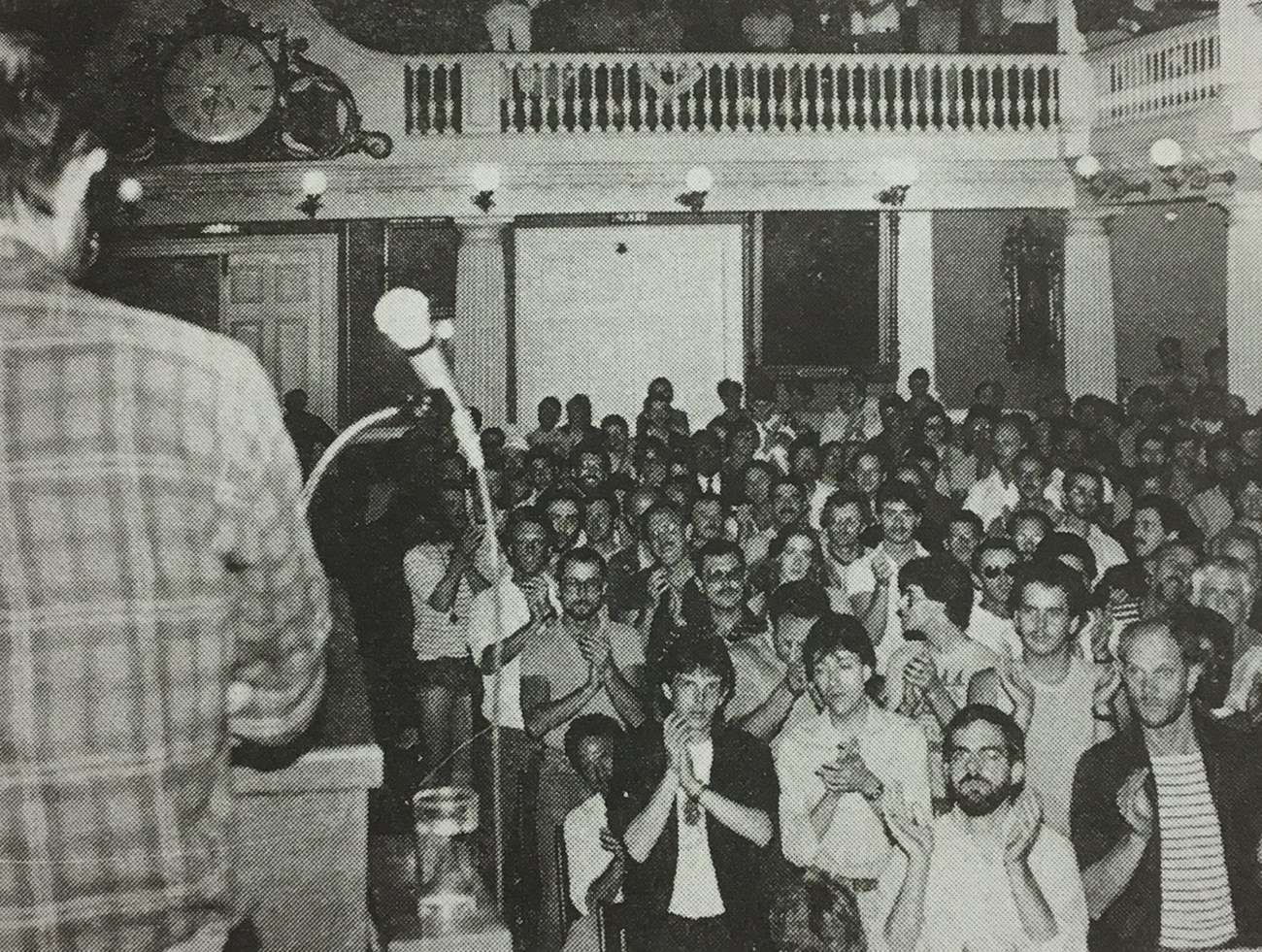

The Boston Globe/Getty Images

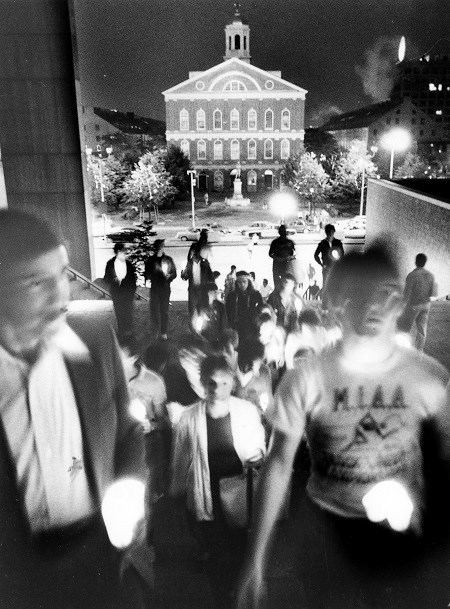

Town Meetings also provided LGBTQ+ organizations with the opportunity to reflect and confront ongoing health issues within the community. Religious organizations such as Dignity and Congregation Am Tikva and health organizations such as the Homophile Community Health Service also did their part to fulfil the community’s spiritual and physical needs from year to year.[12] When the LGBTQ+ community faced a daunting health crisis in the form of HIV/AIDS, the efforts of these groups proved crucial as several town meetings centered around survival. Multiple town meetings in the 1980s concluded with a candlelight vigil, departing from Faneuil Hall and honoring all those who died from the disease.[13]

A number of prominent LGBTQ+ people, of both local and national significance, expressed important ideas in this forum. Author Armistead Maupin participated in the fourth Gay and Lesbian Town Meeting, held in 1980.[14] Playwright and activist Larry Kramer delivered a fiery and controversial speech about the HIV/AIDS epidemic as the keynote speaker in 1987.[15] In his speech, Kramer accused his fellow gay men of having a death wish if they did not fight to make political leaders take AIDS seriously. "Politicians understand only one thing: Pressure. You don’t apply it—you don’t get anything. Simple as that," Kramer insisted, "And it must be applied day by week by month by year. You simply can’t let up for one single second. Or you don’t get anything. Which is what is happening to us."[16]

Few speeches from the Gay and Lesbian Town Meetings still exist today in any form; Kramer’s speech stands out as a call to arms. Two years later, in 1989, Minnesota State Representative Karen Clark and West Hollywood City Councilor Stephen E. Schulte shared the stage and emphasized the necessity of political engagement.[17] The next year, Barney Frank, who represented Massachusetts in the US House of Representatives, spoke on the topic of coming out of the closet and being forcibly outed.[18] Through their leadership, these speakers inspired their audience of hundreds to take action in such important areas as politics and public health.

The Legacy of Gay and Lesbian Town Meeting

"You have taught the state of Massachusetts a lesson about commitment."

– Massachusetts State Senator Michael Barrett, November 18, 1989[19]

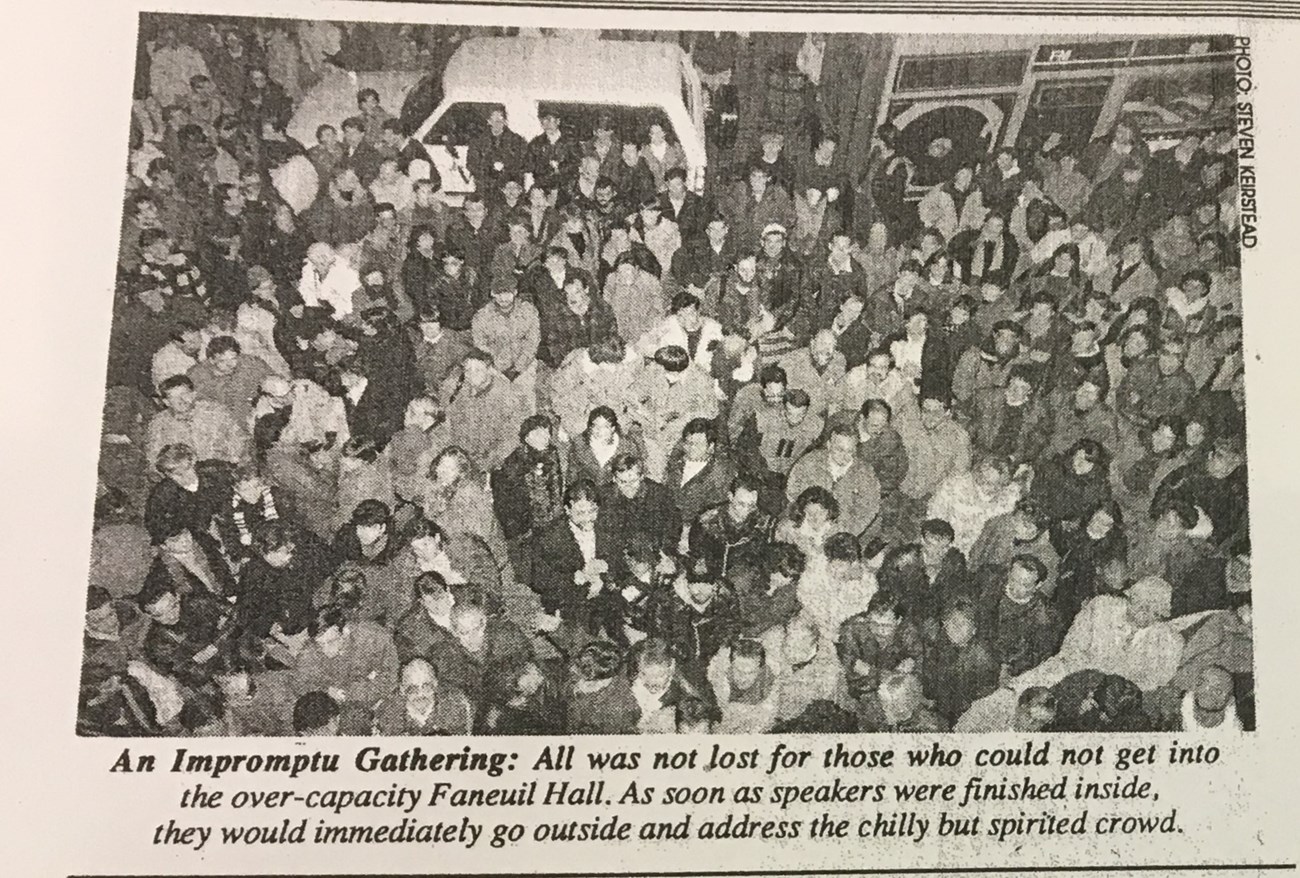

Steven Keirstead, Bay Windows

Though Gay and Lesbian Town Meeting seemed to leave Faneuil Hall for other venues in the late 1990s,[20] its legacy endured. Larry Kramer's speech, for instance, channeled the outrage that many members of the community felt during the HIV/AIDS epidemic; within a year of the speech, the Kramer-backed organization ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) took root in Boston and many other major cities throughout the world.[21] The direct and decisive tactics of this organization changed the course of the epidemic.

In the political sphere, change sometimes came slowly. After a seventeen-year battle in the state legislature, Governor Michael Dukakis signed Massachusetts’s first LGBTQ+ civil rights bill into law on November 15, 1989. Since the bill’s progress had been the topic of conversation at many town meetings over the years, it seemed fitting that, three days later, the LGBTQ+ community gathered in Faneuil Hall to celebrate and to sign their own copy of the bill. As they did so, State Senator Michael Barrett looked back over nearly two decades of persistent lobbying and expressed his admiration for the community's tenacity. That night, as with many events over the course of its storied past, Faneuil Hall filled to its maximum capacity and a large crowd braved the cold to stand outside the doors.[22]

Long after Gay and Lesbian Town Meeting left Faneuil Hall, the spirit of grassroots political engagement engendered there continued to make change possible. In the 21st century, the political awareness and tenacity of Boston's LGBTQ+ community brought about several landmark changes, including the passage of marriage equality. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court’s ruling in Goodridge v. Department of Public Health in 2003 made Massachusetts the first state in the country to legally recognize same-sex marriage. Since the city officials who operate Faneuil Hall do not choose sides on the various issues discussed in the space, members of religious groups met there to protest on the eve of the state’s first same-gender marriages.[23] Today, Faneuil Hall Marketplace has its own Pride Day around the time of the annual parade and, though town meetings no longer take place as they once did, the community remains as engaged as ever in the fight for equal rights.

Contributed by Theo Linger, Park Guide

Footnotes

[1] Judy Harris, “Into the Gay ‘90s,” Gay Community News, June 18-24, 1989, 3.

[2] Craig Kaczorowski, “Mattachine Society,” GLBTQ Archive, accessed March 18, 2020, http://www.glbtqarchive.com/ssh/mattachine_society_S.pdf.

[3] Tony Giarraputo, Interview with John Mitzel, n.d., Prescott Townsend Papers and Photographs, Boston Athenaeum, Mss.L801, Box 1, Folder 11.

[4] “Bromfield Street Educational Foundation Records,” Archives and Special Collections Finding Aids, Northeastern University, accessed March 19, 2020, https://www.lib.neu.edu/archives/collect/findaids/m64findbioghist.htm.

[5] Leon Neyfakh, “How Boston Powered the Gay Rights Movement,” Boston Globe, June 2, 2013, https://www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2013/06/01/how-boston-powered-gay-rights-movement/wEsPZOdHhByHpjeXrJ6GbN/story.html?event=event12.

[6] Larry Goldsmith, “400 Rally for Boston Rights Ordinance,” Gay Community News, June 23, 1984, 1.

[7] Pat M. Kuras, “Boston Community Holds Second Annual Town Meeting,” Gay Community News, July 8, 1978, 3.

[8] Larry Goldsmith, “600 Rally and March For More AIDS Funding,” Gay Community News, July 2, 1983, 1.

[9] “Into the Gay 90’s: Town Meeting 1989,” 1989, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Political Alliance of Massachusetts Records, Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, M91, Box 5, Folder 25.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Kuras, “Boston Community Holds Second Annual Town Meeting,” 3.

[13] Goldsmith, “600 Rally and March for More AIDS Funding,” 1, and Wendy Scott, “Larry Kramer Accuses Gay Community of Death Wish,” Gay Community News, June 14-20, 1987, 3.

[14] “Town Meeting Held,” Gay Community News, July 26, 1980, 8.

[15] Scott, “Larry Kramer Accuses Gay Community of Death Wish,” 3.

[16] Larry Kramer, “I Can’t Believe You Want to Die,” in Documenting Intimate Matters: Primary Sources for a History of Sexuality in America, ed. Thomas A. Foster (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2013), 199.

[17] Harris, “Into the Gay ‘90s,” 3.

[18] “Town Meeting ’90 with Barney Frank,” Greater Boston Lesbian/Gay Political Alliance News, Pride Edition 1990, 1; Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, M91, Box 3, Folder 57.

[19] Susan Lumenello, “Plans for a Party,” Bay Windows, November 29, 1989, 1.

[20] A flier advertising the 1998 town meeting lists the location as Arlington Street Church (“‘Queer’ and ‘Normal’ at the Millennium: The Politics of Representation within the GLBT Community,” 1998, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Political Alliance of Massachusetts Records, Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, M91, Box 10, Folder 12). A newsletter from 2001 lists that year’s town meeting as taking place in the Student Center at Roxbury Community College (Carolyn Federoff, “Town Meeting Set for June 6,” Alliance Reporter, Summer 2001, 1.). The 1996 town meeting took place in Faneuil Hall. No documentation for 1997 or for any year after 2001 has been found.

[21] Activists founded the Boston chapter of ACT UP in December of 1987, six months after Kramer’s speech. “ACT UP/Boston (Raymond Schmidt and Stephen Skuce) collection,” Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, accessed March 19, 2020, https://archivesspace.library.northeastern.edu/repositories/2/resources/933.

[22] Lumenello, “Plans for a Party,” 1, 4.

[23] Jonathan Finer, “Foes of Gay Marriage Rally, Say Fight Isn’t Over,” Washington Post, May 15, 2004, A02, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A28143-2004May14.html?noredirect=on.

References

Finer, Jonathan. “Foes of Gay Marriage Rally, Say Fight Isn’t Over.” Washington Post, May 15, 2004. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A28143-2004May14.html?noredirect=on.

Gay Community News. Bromfield Street Educational Foundation Records, M64. Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, Boston, Massachusetts, United States.

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Political Alliance of Massachusetts Records, M91. Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, Boston, Massachusetts, United States.

Lumenello, Susan. “Plans for a Party.” Bay Windows, November 29, 1989.

Massachusetts Gay and Lesbian Political Caucus Records, M141. Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, Boston, Massachusetts, United States.

Prescott Townsend Papers and Photographs, Mss.L801. Boston Athenaeum, Boston, Massachusetts, United States.

“ACT UP/Boston (Raymond Schmidt and Stephen Skuce) collection,” Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, accessed March 19, 2020, https://archivesspace.library.northeastern.edu/repositories/2/resources/933.

Bromfield Street Educational Foundation Records.” Archives and Special Collections Finding Aids. Northeastern University. Accessed March 19, 2020. https://www.lib.neu.edu/archives/collect/findaids/m64findbioghist.htm.

Foster, Thomas A., ed. Documenting Intimate Matters: Primary Sources for a History of Sexuality in America. Chicago: University of Chicago, 2013.

Kaczorowski, Craig. “Mattachine Society.” GLBTQ Archive. Accessed March 18, 2020. http://www.glbtqarchive.com/ssh/mattachine_society_S.pdf

Neyfakh, Leon. “How Boston Powered the Gay Rights Movement.” Boston Globe, June 2, 2013. https://www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2013/06/01/how-boston-powered-gay-rights-movement/wEsPZOdHhByHpjeXrJ6GbN/story.html?event=event12.