Last updated: January 18, 2023

Article

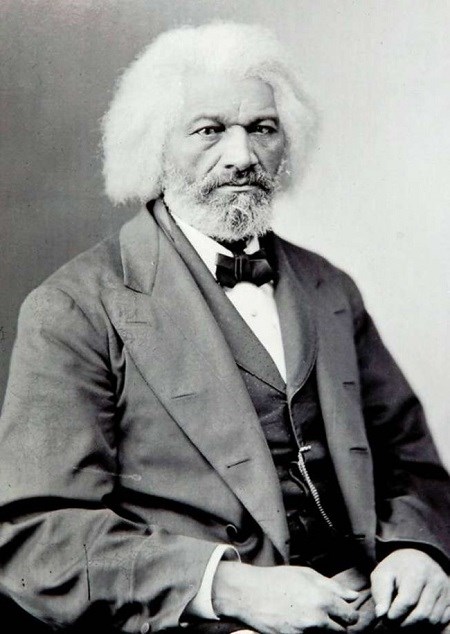

Frederick Douglass: A “Radical Woman Suffrage Man”

Library of Congress

The New England Woman Suffrage Association held its 20th annual convention May 28-31, 1888 at Tremont Temple in Boston. The Boston Globe reported that the "entire floor of the Temple was wholly taken up, the first balcony was packed and the upper gallery comfortably filled. There were enough leaders in the reform present to fill the stage…"[1] These luminaries included Lucy Stone, Susan B. Anthony, and Frederick Douglass among others. Though these leaders clashed over goals and tactics in years past, they set their history and differences aside to join together to celebrate this milestone anniversary and call once again for women's suffrage.[2]

Lucy Stone opened the proceedings with:

This is the twentieth anniversary of the New England Woman Suffrage Society. It brings us to our twenty first year. At that age a young man is invested with his political rights, and becomes a part of the body politic. But the women, to secure whose political rights this Association exists, are still held as minors, without a vote…So our work is still unfinished, and year by year we must ask you to gather here, until an enlightened public sentiment shall finally establish justice for women.[3]

Following her brief opening remarks, Stone turned the podium over to Frederick Douglass to give the first speech of the evening. The audience greeted him "with a hearty outburst of applause" and he "had to stand bowing his acknowledgements for some minutes."[4]

Looking across to those on the stage and out into the audience, Douglass, the seventy-year old veteran of the abolition movement, no doubt saw many familiar faces from his years of activism in and around Boston and New England. Historian S. Jay Walker wrote that the "Anti-Slavery and Woman's Rights movements grew up so closely as to be almost indistinguishable in their earlier period."[5] Acknowledging this shared history, Douglass stated that the women’s suffrage movement "has a valid claim upon my ‘service and labor,’ outside its merits" for it "is composed in part of the noble women who dared to speak for the freedom of the slave...."[6] He continued:

In some respects this woman suffrage movement is but a continuance of the old anti-slavery movement. We have the same sources of opposition to contend with, and we must meet them with the same spirit and determination…[7]

Later in this speech, Douglass invoked the Declaration of Independence in his call for women's suffrage. He stated that the “great charter of human liberty” declared that "all rightful powers of the government are derived from the consent of the governed." Yet, he said, no one has:

been able to state when, where and how woman has ever given her consent to be deprived of participation in the government under which she lives, or why women should be excepted from the principle of the American Declaration of Independence.[8]

His words echoed the arguments long employed by suffragists throughout the years at conventions and events such as the Boston's Women's Tea Party. Using the words and ideals of the American Revolution, suffragists asserted their rightful claim to full and equal participation in American society. These arguments certainly resonated strongly to the audience that night in Boston, a city proudly aware of its central role in the American Revolution.

Acknowledging his long-standing belief in universal rights and suffrage, Douglass declared:

I am a radical woman suffrage man. I was such a man nearly fifty years ago. I had hardly brushed the dust of slavery from my feet and stepped upon the free soil of Massachusetts, when I took the suffrage side of this question. Time, thought and experience have only increased the strength of my conviction. I believe equally in its justice, in its wisdom, and in its necessity.[9]

He concluded his powerful speech with an "earnest plea that the ballot be given to women."[10] He said:

if…human nature is more virtuous than vicious, as I believe it is, if governments are best supported by the largest measure of virtue within their reach, if women are equally virtuous with men, if the whole is greater than a part…then the government that excludes women from all participation in its creation, administration and perpetuation, maims itself, deprives itself of one-half of all that is wisest and best for its usefulness, success and perfection.[11]

The Boston Daily Advertiser considered this the "most elaborate and eloquent speech of the evening…" after which Douglass "received a prolonged applause; nothing less, indeed, than a most enthusiastic encore…"[12]

Later in the convention, Douglass reaffirmed the principles and commitments set forth in his speech by vowing that "whatever time may be given me on earth, be it little or much, will be devoted as far as I am able to this great cause of woman."[13]

Footnotes:

[1] Boston Globe 29 May 1888, p. 5.

[2] For more information on the split in the women’s movement, please see "Fighting for Suffrage: Comrades in Conflict"

[3] Woman’s Journal 2 June 1888, p.1.

[4] Boston Globe 29 May 1888, p.5.

[5] S. Jay Walker, “Frederick Douglass and Woman Suffrage.” The Black Scholar 4, no. 6/7, BLACK WOMEN'S LIBERATION (March-April 1973), pp. 24-31.

[6] Frederick Douglass, “I am a Radical Woman Suffrage Man: An Address Delivered in Boston, Massachusetts, on 28 May 1888.” Found in The Frederick Douglass Papers: Volume 5, Series One: Speeches, Debates and Interviews, 1881-1895, ed. John W. Blassingame and John R. McKiving (Yale University Press, 1992.): p. 379.

[7] Douglass, "I am a Radical Woman Suffrage Man," p.381.

[8] Douglass, p. 384.

[9] Douglass, p. 383.

[10] Boston Globe 29 May 1888, p. 5.

[11] Douglass, p 387.

[12] The Boston Daily Advertiser 29 May 1888 p. 5.

[13] Woman’s Journal 9 June 1888 p.2.