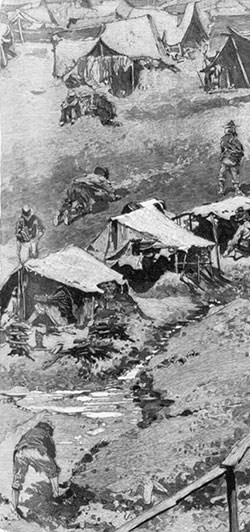

Library of Congress (LC-USZ62-51084) Often referred to as "shebangs" the rough shelters improvised by prisoners were known by many names: shelters, huts, tents, shelter tents, blanket tents, and many others. Shelter, or lack thereof, was a defining part of the Andersonville experience for many prisoners. The Confederate quartermaster officer assigned to Andersonville, Captain Richard Winder, was ultimately responsible for providing the prisoners with shelter. Because of the location of sawmills, the need to provide timber to the railroads, bureaucratic red-tape, inflation, and general incompetence, Winder was never able to successfully accomplish the task. Left to fend for themselves, the prisoners did the best that they could to build their own shelters, with the limited resources available to them. Prisoner diaries and memoirs document seven common types of shelters:

Others, less ambitious or lacking necessary resources, scooped out holes in the sand or clay. Here they bunked, but since there were no covering they suffered from the heat and rain. Three or four men could pool their resources to dig a hole about three feet deep and then scoop out the earth at right angles to it. Into these caves they would crawl and be protected against the heat and storm, but they were plagued by cave-ins and several of the troglodytes were smothered in their sleep. Some employed pine boughs for protection. Private Robert Knox Sneden, who survived his time at Andersonville, described the shelters as follows:

While opting to live above ground himself, Sneden's account of life at Andersonville does give a number of clues that relate to construction of shelters. Sneden stated that overcoats, blankets, India rubber blankets, and pine boughs were often used to roof various structures and also mentions that they used ripped shirts for lashing material. Some of the more inventive prisoners used hand carved shovels that were hardened by fire to dig their pits. After the new northern addition to the prison was opened for occupation, Sneden recounted how Union prisoners quickly began constructing shelters:

Ironically, these pit shelters were not only intended to provide protection against the weather but also against possible cannon fire, as several of the cannons faced the interior of the prison in case the prisoners rioted. Private Robert Knox Sneden stated that in the summer of 1864 some of the men began digging new holes as they thought the cannons would one day fire into the prison ). These holes were very deep - almost a meter below surface. Their subterranean nature had several purposes, the most important of which was providing shelter against a cold wind or a scorchingly hot day. Combined with some type of roof, there would also be limited protection from the rain. Also the soil at that depth is generally cooler, thereby providing some measure of comfort on the hottest days. Some of the walls in the pits were curved rather than vertical, thus providing a more comfortable place to sleep and spend the days waiting for the war to end. |

Last updated: September 4, 2022