Robert Knox Sneden diary, 1861–1865 (Mss5:1 Sn237:1), Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Va Park staff regularly hears from visitors who say, "My ancestor escaped from Andersonville." While it is possible that a certain visitor's ancestor escaped from the stockade at Andersonville, it is extremely unlikely. Despite popular portrayals of escape in films and prisoner memoirs, postwar U.S. Army records indicate that out of the 45,000 prisoners held at Camp Sumter during the course of its operation, only 30 to 40 men successfully escaped to ultimately reach Union lines and rejoin their units. This means that less than one-tenth of one percent of prisoners ever escaped successfully from Andersonville. With the nationally followed trial of Captain Wirz from August to October of 1865, Camp Sumter's infamous reputation began its advance to the forefront of the American public's memory of Civil War prisons. Eventually, Andersonville's reputation would almost completely eclipse that of other Confederate prisons.

NPS/A. Marsh Correspondingly, countless survivors of Confederate prisons other than Camp Sumter began to falsely claim imprisonment at Andersonville. Many men who escaped from other prisons within a 60 mile radius of Camp Sumter, or from train cars coming to or near Andersonville, would later tell stories of daring escapes from the clutches of Andersonville itself. As a result, most tales of escapes from Andersonville are more accurately escapes from places near Andersonville. Additionally, Victorian notions of manhood and bravery dictated that a soldier's actions while on the battlefield defined his character. For men taken as prisoners during the Civil War, this opportunity to "prove oneself" as a man was lost—by "allowing" themselves to be taken captive, they provided what was to many of their contemporaries definitive proof of their cowardice. As a result, many prisoners faced the choice of either returning home after the war to be received as failures, or to attempt a dangerous escape. Those prisoners at Andersonville and elsewhere who never successfully escaped would often invent escapes or escape attempts in order to validate themselves in the eyes of their society.

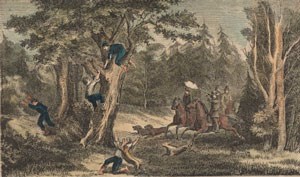

Robert Knox Sneden diary, 1861–1865 (Mss5:1 Sn237:1), Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Va In reality, escape from Camp Sumter had an extremely high rate of failure. For a Union prisoner to make a successful attempt for freedom from the prison compound, he had to make it past stockade walls, guards, artillery surrounding the stockade, local militia, citizen mobs, and patrols with tracking hounds. Patrols for Confederate deserters and escaped slaves often caught escaped prisoners as well, sending dozens of men back to the stockade. Although tunneling was frequently described in post war memoirs, digging out of Andersonville was in reality a very ineffective form of escape. Potential tunnelers faced exposure by informants, probing for tunnels by guards, discovery when gathering as a group or discharging dirt, tunnel collapse, and loss of direction. Successful escapes more often involved techniques like bribery and disguise, which were more reliable and therefore safer. By bribing a guard, a prisoner might make his way into a group soon to be exchanged, or onto a train leaving the area. If a prisoner were lucky, disguising himself as either a prisoner in an exchange group (sometimes as one who had died) or as a Confederate guard could mean that he would soon be bound for freedom. It is crucial to remember that although escape from Andersonville was possible, successful escape all the way back to Union lines was virtually unheard of. For many prisoners, "escape" meant only a fleeting reprieve from the misery of the stockade, perhaps long enough to gather kindling or food, but by no means a permanent condition. Written by Heather Clancy, July 2013 |

Last updated: April 14, 2015